Renowned as the oldest and most quintessentially German of the world’s contemporary art fairs, Art Cologne is a connoisseur’s destination of choice, where slow and careful strolls down the aisles can reveal treasures from the less flashy high points of the past half century’s art. It is a garrulous place, for animated conversations between ardent collectors, and it has found an appropriately pedigreed match in its director, Daniel Hug.

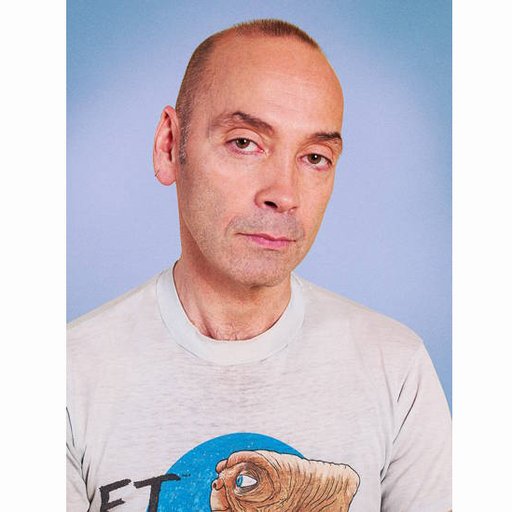

The grandson of the great Bauhaus paragon László Moholy-Nagy, Hug cut his teeth with roles at American fairs like Art Chicago and Art L.A. and as a dealer himself before being named to the venerable post in 2008—roughly a half century after Art Cologne was founded by the dealers Hein Stünke and Rudolf Zwirner (known to non-Euros as the father of David Zwirner).

But what is the role for a locally focused fair like Art Cologne in today’s globalized art landscape? To find out, Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein spoke to Hug (who is married to the Cologne gallerist Natalia Hug) about the history of the fair, and where it finds itself today with its unique partnership with NADA.

To begin, why Cologne? Why did the dealers Rudolf Zwirner and Hein Stünke choose the city as the location for the first contemporary art fair?

Well, when the Allies divided Germany between the East and West after the war, East Germany came under the control of the Russians while West Germany was broken up into three different sectors—one controlled by the French, one controlled by the British, and one controlled by the Americans. Until the end of World War II, Germany’s capital was Berlin, but afterwards the new capital of West Germany became Bonn, which is a city located about a 20-minute drive from Cologne.

Germany made a very quick recovery after the war—they call it the Wirtschaftswunder, or “business miracle”—and so suddenly money came flooding into the Ruhr Valley and the Rhineland, which became the functional center of the country. Cologne was the largest city in the area at the time, and while Frankfurt had all the banking, it's only a two-hour drive away from Cologne.

Rudolf Zwirner actually started his gallery in Essen, an hour away from Cologne, but he became inspired by all the artists who were living and working in the city, and so he moved his gallery to Cologne too in 1964.

What was the art scene like there?

With Berlin out of commission after World War II, Cologne basically became a cultural center for the time. There were artists in the city like Mary Bauermeister, an eccentric figure who was married to the avant-garde German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen and who had spent time in New York with John Cage. She opened a studio at Lintgasse 28 in the center of Cologne in 1960 and began organizing fluxus events with the likes of Cage, Christo, Wolf Vostell, George Brecht, and Nam June Paik, and I know Rudolph Zwirner attended some of the concerts and art happenings that took place there.

Hein and Eva Stünke’s Galerie Der Spiegel—which means “the mirror”—was one of the first galleries to open after World War II, in 1945, and showed key postwar and Modern artists like Max Ernst, Wols, Hans Hartung, Henri Laurens, Fernand Léger, Marino Marini, Henri Matisse, amongst others. So Stünke was a very important man in the art scene here, and it was only natural for Rudolf to begin working with him when he moved his gallery to Cologne.

Where did they get the idea to start an art fair?

They were actually inspired by the dOCUMENTA exhibition in ‘64—they both went to see the show [curated by Arnold Bode and Werner Haftmann] and thought, “This is fantastic—why not make something like this where you can buy art?” Hein Stünke was also a consultant on dOCUMENTA II in 1959, a role he performed until 1972. So the idea from the beginning was to create a dOCUMENTA-like thing, except that they would invite galleries to bring the contemporary artists involved.

The idea of an art fair, after all, isn’t new. There have been art fairs forever, but they were basically flea markets or antique fairs where dealers would bring antiques and works by dead and forgotten artists. The notion that a contemporary art gallery, representing primary-market work by living artists, would do a fair was a pretty abstract idea.

The funny thing is that people were unsure what would happen—like, “Is this gonna work?” There were previous fairs, like an art and antiques fair in Munich that was started in the ’50s, but no one had ever seen contemporary art at a fair. So, the first Art Cologne—or as it was called, Kunstmarkt Köln—started on the 13th of September and went to the 8th of October. It was almost a month long.

How was it organized?

They did it in two parts, so each gallery basically had two booths. One part was a group show of artists in the Kölnischer Kunstverein, and the other part was in the Gürzenich festival hall, where the galleries had booths—your standard square boxes—and presented their programs. Everyone had two ways of presenting the works, but there were only 18 galleries at the time.

And everything was for sale?

Hell yes everything was for sale. They collectively pulled in over a million Deutsche Mark, which was a lot of money in the ‘60s. Everyone was amazed. People just thought it was going to flop, but it was a huge success.

It’s interesting that the fair was inspired by dOCUMENTA, since that exhibition was launched in 1955 as an effort to bring humanism and the arts back to the rubble of an utterly defeated Germany. Was Art Cologne born from a similar idealism?

I don’t think it was idealism—it was just a group of German gallerists who were trying to figure out how to get the market going again in the late ‘60s. They figured, why not make a big festival?

How did it evolve from there?

Well, the first year they only allowed German galleries, because the dealers were afraid that if they make it international then suddenly they would have to compete with more established galleries. I mean, for Zwirner, who represented American Pop art in Germany, it wouldn’t have made logical sense to invite Leo Castelli to sell his Pop artists to sell to Zwirner’s clients. But then, in the second year, Düsseldorf launched a similar art fair called Prospect 68 that invited international galleries. This kicked the Kunstmarkt Köln into high gear, and they said, “Ok, you know what? We’ll let international galleries participate too—but they only get a wall, not a booth.”

There were legitimate concerns about market share and market control that hadn’t been quite figured out yet, but by 1969 the fair had grown to about 60 exhibitors. By 1986, it had 185 galleries. Then there was a moment in 1990 when it got up to about 370 galleries, so it was a huge monster, and that was the high point. It was the most important contemporary art fair in the world.

Where did the fair’s collectors come from? Was it primarily a Cologne collector base, or was it German collectors, or was it a broader European audience?

In the beginning it was just Germans for the most part, but within a few years the Belgians and Dutch came in, and their galleries began taking part in Kunstmarkt Köln, like Wide White Space from Antwerp and Art & Project from Amsterdam, which were the key, cool galleries at the time. Soon the rest of Europe joined, and it became very difficult and competitive to get into the fair. The organizers were seen as snobs. That’s why, in 1970, Art Basel started—the dealers Ernst Beyeler, Trudi Bruckner, and Balz Hilt couldn’t get into the Kunstmarkt Köln, so they created an enormous fair in Basel and let everyone in. Off the bat they had 150 galleries, I think. It was a free-for-all. You had to build your own booth, too [laughs].

Did they set out to compete with Cologne?

No, they started Art Basel in June, and it was just a very big and very conservative operation. There weren’t any contemporary art galleries who were doing it—it was mostly dealers with Modern, blue-chippy stuff.

So, what were some of the signal, historic artworks that were debuted at Art Cologne over the years?

Oh, quite a few. Probably the most famous in the early years was in 1969 when the Berlin gallery René Block presented Das Rudel, or “The Pack,” by Joseph Beuys, which was this huge installation of a grey Volkswagen bus with about 30 wooden sleds coming out of its rear, each with a grey felt blanket tied to it along with a flashlight and some fat. That sold for a 110,000 Deutsche Marks, which was a record price at the time for a living German artist.

Amid the globalization of the art market, Art Cologne’s gallery list has a charming throwback feel to it—if you look at the cities where your exhibitors are coming from, it reads like a cast reunion of the principles from the two World Wars, excepting Russia. It’s predominantly Germany, Austria, France, and Northern Europe, with a smattering of Britain and the United States. What exactly is the collecting landscape like in Germany these days?

I would call it a strong market for contemporary art, and actually for Modern and postwar as well. The thing is you have to realize is that a lot of these collectors, the older ones, went through the big crash of the ‘90s, and so they are hesitant to spend more than $150,000 for art. In the U.S., on the other hand, you have many young collectors who make a lot of money in banking or stock market who are dropping a couple million here and a couple million there on stuff that might not hold its value in a few years. But these people will be really bummed when the painting they bought for a million bucks goes down to $70,000 at auction 10 years later, right?

And this happens. An older dealer in Cologne told me once that in the early ‘90s that there was a meeting of the Museum Ludwig’s benefactors, and suddenly the collector Michael Stoffel stood up and said, “Colleagues, I have to talk to you about something that has made me very angry.” And he said that a certain gallery had just sold him a Günther Förg painting for 220,000 Deutsche Marks, which back then was a lot of money for a contemporary artist, and that another one like it had just sold at auction in New York for 20,000. “How can this be?”, he wanted to know. Because if you look at the ‘80s art market boom, it wasn’t the auction houses that were breaking records—it was the galleries that were boosting the prices. It was crazy.

But, anyway, I think a lot of the older collectors are now buying in a very sensible, informed way. Dealers who come here thinking, “Hey, I’ve got a bunch of newbies in New York who are spending $100,000 on an artist who’s had two gallery shows and not one single institutional show”—well, that’s not going to work in Germany. These collectors are looking for art at normal prices.

I mean, art and collecting are engrained into the society here. It’s part of the culture. It’s not like in the U.S. where it’s only in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Chicago. It’s different—you find collectors all over the place, you have galleries everywhere, and we have 300 kunstverein in Germany. Going to a museum is standard for most Germans—it’s like literature. It’s not only for the well-to-do.

How does an art fair director such as yourself cater to such an audience? What are they looking for?

It depends. You know, it’s funny—we get two or three English-language reports on Art Cologne, and then we have a stack of three hundred in German. It’s insane. I was blown away by how big a deal it is when I started here. A little while ago I walked into a China shop near my house, where I’ve only been once before, and the woman said, “So, you must be a lot of stress at the moment.” I said, “What are you talking about?” And she said, “The fair’s coming up, right?” I thought, “Holy shit.”

So you’re a celebrity in Cologne.

[Laughs] I was like, “Cool!” But it’s weird—the woman knew Sigmar Polke. It’s just a very well-informed audience. So there’s nothing more important for galleries to do at the fair than to simply talk to people about the art they’re hanging and really engage. There are very few art consultants here, actually. In the U.S., it’s all being taken over by art consultants—there are art consultants everywhere. At least that’s what the galleries tell me. It’s an explosion of art consultants. In Germany, I only know of two who do it professionally, and one is in jail for overcharging a client 10 percent. People buy art from love here, not just to make a quick buck.

You have a very dynamic mix these days, with the more blue-chip, museum-ratified work in Art Cologne and then, in NADA’s COLLABORATIONS sector, more avant-garde fare that’s less easily assimilable off the bat from a museum context. How do audiences respond to the combination?

They love it. This idea to work together with NADA was really, really brilliant, because the Germans were into it immediately. They were like, “This is so fantastic—what a genius idea!” And what’s nice is that the roots of Art Cologne—how it started with Kunstmarkt Köln—really parallel how NADA started, as a gallerist-run initiative. It’s even the case that when Hein Stünke and Rudolf Zwirner first tried to obtain access to the Gürzenich hall from the city of Cologne for the fair, they had to create a nonprofit organization that they called the Association of Progressive Art Galleries.

So it’s really been a terrific partnership. And I like the idea of a fair within a fair—of an autonomous fair inside a big fair. I had an idea once that it would be amazing to do a fair of fairs, to invite 10 different art fairs to all join together and make a big fair.

How would that work?

Well, maybe ARCO would bring the top 10 Spanish galleries, Artissima would bring the top 10 Italian galleries, Frieze could bring the top 10 English galleries, and FIAC could bring the top 10 French ones. You could get Art Beijing too, because who knows their own countries better than the people doing art fairs there. You’d have these different sections—and the food would be amazing!

What an great idea—you should do it!

We could do it. I know we’d do it in Iceland. Heather [Hubbs, director of NADA] and I were talking about that once—I think we even came up with a name: “Deep Freeze.”

Now, everyone in Germany goes to Art Cologne, which traditionally takes place a week before the other big art-market event of the season, Berlin Gallery Weekend, when that city’s scrappy galleries band together to entertain an influx of visiting collectors. This month, however, a kerfuffle has erupted because of the announcement that next year Art Cologne will move back a week, to overlap with the Berlin festivities—leading some Berlin galleries to despair about their ability to do both events simultaneously. To ask a simple question: why is Art Cologne moving back a week?

Because of the Easter school holidays in North Rhine-Westphalia, which is the region we’re in. Every year the schools in the Rhineland close for two weeks for the Easter holidays, and so Art Cologne always takes place one or two weeks after the school Easter holidays. Next year, Easter, which goes by the Catholic calendar, is moving back a week—every four years it happens late—which means I have to move back a week too, which puts Art Cologne on Berlin Gallery Weekend. But if the fair took place during the Easter school holidays, none of the collectors would be here. They’d be all skiing or in the Bahamas or Majorca, and that would be a really big waste of time for everyone.

That seems like quite the jam.

Now some of the press have reported that our move is due to scheduling issues with another fair at our venue, but that’s not the case. That’s totally wrong information. But, anyway, we’re in discussion with the Berlin galleries, and I think once everything simmers down we can figure out a solution. But, for now, our date is basically set. We’re not moving that date.

Do you think that’s going to split the available collectors between the events?

Are you kidding? I know that collectors from continental Europe and overseas are going to be thrilled to be able to see two major events in one week. It’s totally possible.

So, to round things down, you’ve done fairs in Chicago, you’ve done fairs in L.A., you’ve worked with all kinds of collectors all over America, and you’ve obviously dealt with galleries all over the world. What does Art Cologne need to do to stay competitive in the international art market? Does it need to stay local and dig into its roots, or does it need to expand into other markets?

I think the German market is huge. It’s big enough for us. This concept of creating a fair that reflects the global art market? It’s impossible. You’d have to have a thousand galleries, and nobody is able to walk through a fair with a thousand galleries. Some fairs are addressing this challenge by opening satelitte fairs on other continents. But, in a way, that really goes against the true nature of what an art fair really is.

An art fair is about celebrating and investing in a specific place, ultimately bolstering and supporting the art infrastructure and working with the traditions and culture specific to that place. It is not about creating a domineering global conglomerate, like Nestlé, leading only to a global monoculture, destroying the delicate intricacies and regional identifiers of our diverse human culture.

Art Cologne is fine. The thing I relish the most is that people don’t do the fair because of hype. They’re not doing it because of fashion. Dealers actually do it because they do well here. I don’t have to advertise to get people with food—I don’t have to say, “Hey, we’ve got the best pizza in Cologne, from a place where you can’t get a table any other time, but here you can stand in the line to get your pizza.” That’s not what it’s about. Art Cologne has been around for 50 years and it’s going to continue for another 50 years. It is what it is.

The thing is, you have obligations as an art fair. Most of the older galleries at Art Cologne were doing Basel five, 10 years ago and were eventually either kicked out or displaced or decided not to do it anymore. So while there’s always going to be something new, cool, and trendy, you also should support these older figures. And there are a lot of galleries in Germany that don’t fit into the typical model. So what if you’re not a “young gallerist,” because you were 65 when you opened your first gallery?

If we eliminated these people, do you know how many famous galleries that wrote history would be discounted? It’s baloney. Gallerists come in all shapes and sizes, all ages, and they all have unique visions and ideas. Not all of them are good. But at Art Cologne, if they’ve been doing the fair for a long time and they’re still doing it, they’re pretty amazing. They warrant a closer look.