On a winter’s night in 1970, police shot down a suspect outside the midtown hotel where songwriting partners Bernie Taupin and Elton John spent their first night on tour in New York. The harrowing incident, together with the low temperatures and the feeling of being a stranger in a strange place, drove the then-20-year-old Taupin to seek solace in the city's galleries and museums—particularly the Museum of Modern Art, where he discovered unexpected crossovers between the Modernist aesthetic and his own songwriting.

A 15-year-old dropout with no formal musical or artistic training, Taupin remains best known for his over 40-year collaboration with the "Rocket Man" singer that resulted in platinum albums like “Don’t Shoot Me I’m Only the Piano Player” and “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road,” launching the pair to stardom. But, outside of the incredibly productive partnership, Taupin also nurtured an acute visual sensibility and infatuation with the revolutionary developments of Modernism. Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still rose to be his idols, and after settling down from a musician's itinerant life on the road in the 1990s, he traded the pen for the paintbrush.

Today Taupin lives in the country north of Santa Barbara, California where he’s transformed an old racquetball court into a painting studio. It’s a fitting space for the artist who is “big on throwing things around,” as he says. Riffing off 20th-century artistic traditions, Taupin delivers his own distinct inflection with thick dramatic layers of paint, in which he finds a visceral satisfaction and obsessive pull he never experienced in writing lyrics.

During Frieze week, Artspace spoke to Taupin about the overlap in the art and music worlds, the baggage that comes with celebrity, and how to title a painting.

Your mother and maternal grandfather instilled in you a love of poetry and music as a child. What about fine art—where did that interest come from?

One of the first things I remember is sitting on my mother’s knee looking at J.M.W. Turner pictures in this big book she had. What appealed to me was not so much a sense of the art, but rather a sense of the adventure within the art, because I had a very fertile imagination and didn’t play rudimentary childhood games—I would invent my own scenarios. And Turner’s paintings were so vivid, you know, with a lot of sea battles. So fine art was always in the back of my mind, but I became entrenched in the music business at 17 years old. I was on the road and when you are young like that, you tend to get into habits that are not necessarily artistically driven.

What do you mean exactly by that?

You are just living your fantasies basically. I’m not talking about bad habits, I’m just talking about your better judgment, and your artistic eye seems to go out of the window. It took coming to New York the winter 1970 or ’71 to return to it.

What was your familiarity with contemporary art up until that point? Did you go to galleries in London like Whitechapel and Marlborough in the 1960s?

I tended to find myself in the Old Masters sections as opposed to the modern. I didn’t know where to go in order to find that and wasn’t totally aware of it. I was very aware of Pop art, people like Warhol, the obvious things, you know, because they were so apparent in my everyday life. It kind of went hand in hand with music, like Velvet Underground’s relationship with Andy Warhol.

Beyond these cross-genre artistic collaborations, did you see overlaps in what you were doing with pop music and the contemporary visual arts?

It was probably a very juvenile sensibility, but the beauty of abstraction to me was not really knowing what it was about and coming up with your own interpretations. And I think that appealed to me, because it was related to what I did as a writer. I prefer people to come up with their own interpretation of things as opposed to have to literally explaining to them what a particular piece is about, and I think that works doubly for abstract art. I mean, think of that famous quote from Andy Warhol: “What does it mean to you?”

You’ve said before that the sonic and visual expression both come from the same place for you.But your lyrics evoke images and clear narratives, and looking at your art, well, the canvases are diffuse fields of color and abstractions. There doesn't appear to be an overlapping aesthetic.

What you are saying is a compliment to me, really. There is a stigma around “celebrity art”—I just loathe that tag—I think one of the problems with that is that a lot of people who come out of the music or film business and also paint or create in this medium tend to bring the baggage from that one into this. And this is not to be detrimental to any of those people. It is like Ronnie Wood, who continually draws pictures of the Rolling Stones. You are not dividing the palette there.

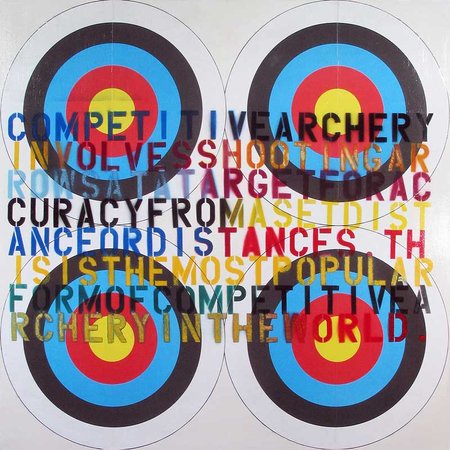

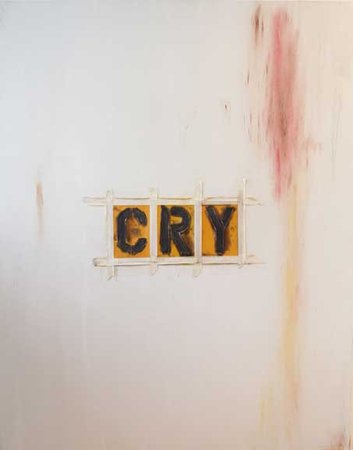

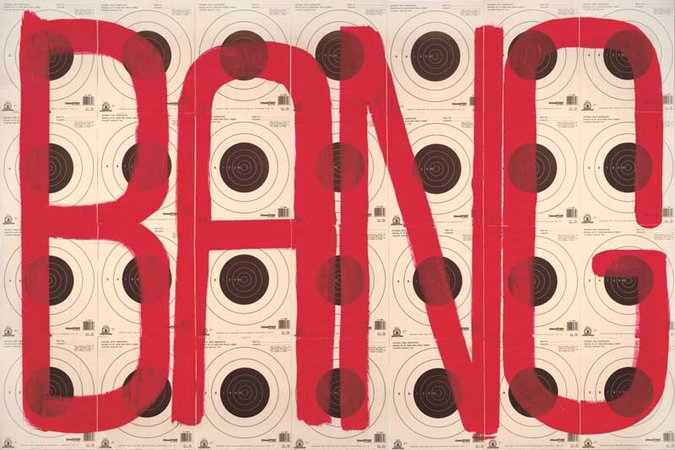

Some of your recent canvases include short lapidary phrases. Were you wary of including words on your canvases, that it would create an extension of what you did in the musical field?

Yes, and that goes back to what I am saying about being afraid that it would connect me back to the writing and the lyrical thing. I think with gaining confidence, I’ve learned to believe that it's okay, that’s alright. It really isn’t relevant, and it really doesn’t relate back to that. And the text pieces I do are just very minimalistic. It’s bam, there’s a word. It is a word that will again, hopefully, ignite the viewer to think. And I think that’s the crucial bottom line of abstract art—to invite the viewer to think. What I’ve wanted to do artistically on canvas has no relationship to my music whatsoever. But at the same time, they still tell a story. I’ve always thought of myself as a storyteller.

What are the stories your canvases tell?

I want people to look into them and find what they want in them. I suppose they do tell a story, because the story is the creative movement across the canvas. But I don’t want that to sound pretentious, because at the end of the day, I do what I do because I enjoy color, I enjoy multimedia. And it is fun, and it is a whole different feeling than when you are writing a song.

How are those processes of writing lyrics and splashing paint on a canvas different?

I love the process of making music, going into the studio, seeing the song come together. But once that song is complete, on disc, and it is released, I never listen to it again. That is not the same as with my artwork. I don’t want to have to say I enjoy painting more. But I suppose the bottom line is that it is a different process and is more invigorating. It is more physical, definitely more physical. When I write, I write very fast. Ideas come to me very quickly. I write in the moment. I don’t come back to things. As far as songs are concerned, I work off of titles—you know, I come up with titles and write them on the back of a napkin. If I’ve got a title, it means I have an idea, whereas that is not the case with paintings.

How do you think about titling your paintings?

The titles of paintings are sort of like handles—they are just a way of identifying things. With songs, I have a title, and the story comes under the title and that defines that; whereas with paintings, I’ll really give them handles, because I will finish something, and I’ll look at it, and it is really the first thing that comes into my head. Well, what does this say to you? And it’s like that with the newest piece that I’ve done, a multi-layered, modeling-paste-based piece called the Descendants of Oz. And why it’s called that, I don’t know. It is what appealed to me and what came into my head.

Do you listen to music when you are painting?

Oh yeah, absolutely, absolutely. I’m a jazz and blues guy. It varies I think—it just depends on what I’m working on, too. You know it’s like, I’ve always said that colors indicate moods and I think they also indicate music. There are colors that symbolize jazz. I think there are colors that symbolize old time country music. I don’t say the darker colors symbolize jazz and blues, but the darker, the more complex the color and the music. The brighter, more straight-out-of-the-tube stuff, I’d probably be listening to the Louvin Brothers or George Jones. But it does control the playlist.

Another intersection of music and art is the album cover. You and Elton John put a lot of thought into yours. I think of “Captain Fantastic and the Brown Dirt Cowboy” which has artwork by the legendary Alan Aldridge, who worked with Penguin and the Beatles in the ’60s and ’70s.

I’m a vinyl man. I still play vinyl. And I worked hand in hand on all of our earlier album covers and was very close with Alan. But, yeah, I was very instrumental in that whole Captain Fantastic thing. Album art, that was definitely a whole ball game of its own.

You have some 50,000 vinyl albums. What about art—do you collect?

I actually don’t collect art, but I collect photographs—basically of old-time musicians. They are of unusual pictures of iconic musicians. When I say unusual, for instance, in one of the bathrooms, there is this guy with kind of protruding ears and slicked-back hair and looking straight at the camera, very rural, very kind of oaky looking. And people will go in there and they’ll go, “Who’s that picture of?” And it’s Hank Williams’ drivers license photo! I have another picture of this very unusual-looking couple, big photograph, again very rural looking, really bad fitting suit, and lady with a handbag, guy with a cigarette in his hand. Johnny Cash’s parents! I’ve got a picture of Bob Dylan standing on his head, you can’t see his face because it’s like in long grass—you only see half of his head. They’re all the people I sort of lionize as great figures in the music world.

Elton John is a collector, too. Does he own your paintings?

He has about four of them. He’s got good taste. The last one he bought was fantastic. The minute he saw it, he said, “I want that.”

Do you find your celebrity as baggage when being taken seriously in the art world?

When I first started showing, there was baggage that came with it. In a gallery setting, I’m pretty available—I’m happy to talk to people. The unfortunate thing when it comes to me is that I get guitar pickers who turn up with the brown bags full of record albums. That is something I’ve learned to live with during the initial phase, but now I really don’t have a lot of patience for it. I have no qualms about knowing where I come from, but it is very important to legitimize with what I do. Like Duke Ellington said, “Everyone should do two things.” And it is distracting when you get that element coming in.

What about the people not bringing memorabilia for signatures—by which I mean, coming from the music world to the art world, do you see differences in audience and guardians at each set of gates?

Yeah, I think there are. I think the art world is looked on by a certain group of people as being a bit narcissistic, unforgiving and brutal, and some might say pretentious. But what am I going to do? I know it sounds naive and base, but I can only do what I do. And I hope to be accepted and regarded with a certain amount of respect.

But I don’t know. I’ve met so many great people. I’ve never really run into anybody who’s been particularly asinine or cruel. But I suppose it can be a cruel world. I’m not going to stop doing it because somebody doesn’t like what I do, or has a negative opinion of what I do. I think every major artist worth his salt has his detractors. I’ve been doing what I do for a long time, and you’ve got to put on a Teflon jacket.

Do you care if you are labeled as a musician-artist or an artist-musician?

I’m a great believer in that if you want to try something, there is no harm in trying it. You may find out that if it is not working for you, then you go do something else. There is nothing that says that a plumber can’t go home and make model airplanes, because he enjoys doing it and he might be good at it. I’m somebody who wrote songs but wanted to paint. And painting has become the foremost thrust in my life. It is what I enjoy doing. I am happiest when I am doing that. I’m happiest when I’m home around my family, in my studio, cranking the music and throwing paint at things. It is a million miles away from my musical association. It’s so radically different. I just don’t feel like a musician or whatever I’m termed as. I mean, again, handles are very difficult to get comfortable with. It’s like when somebody who doesn’t know me asks what I do… I just say I’m an artist.