With a few exceptions, the artist has historically been found wading around at the bottom of the art-world food chain. Though the existence of the art market relies on the fruits of his or her artistic labor, the artist’s livelihood has long depended upon the systems, codes, and hierarchies that structure the art world. Without galleries to broker sales, wealthy collectors to drive demand, and museums and institutions to offer associative prestige, the artist is without an audience, without an exhibition space, and without a paycheck.

Or at least, that was the case before the internet. Now, artists can post their works online and connect with new audiences on their own. But how this agency might convert into dollars is a problem that most artists have yet to fully crack—a problem that, for now, may be what is keeping the gallery system vital.

But one artist in particular, Josh Citarella, may have figured it out—and not because it was his only option. The young New York-based artist has had his fair share of success exhibiting in the traditional sense. He’s represented by Higher Pictures in New York and Carroll/Fletcher in London, and has come to bank on the sales of his artworks through conventional means. Maybe it’s because of Citarella’s immersion in the market that he’s able to catch a twinkling glimpse of the escape hatch.

Citarella and fellow artist Brad Troemel have shared a history of disrupting the art-world status quo. They’ve recently spawned a collaborative project they call Ultraviolet Production House, which, though firmly rooted in the discourse of Post-Internet art, has expanded its definition to include not only the way in which art is disseminated and consumed by audiences online, but the way in which actual art objects can be realized through web-based platforms and businesses like Amazon and Etsy. Previously, the two worked (along with seven other artists) on the Jogging, a Tumblr project that prioritized the documentation image over the material art object.

So, why is fine art the last industry to successfully utilize e-commerce? Here, Artspace’s Loney Abrams racks the brain of an artist who’s not only speculating on the future of the art market—he’s making it.

Renounce Citizenship and State Affiliation emancipation government ID cards into guitar picks (Sovereign Citizen) revoke worldy government by Ultraviolet Produciton House

Renounce Citizenship and State Affiliation emancipation government ID cards into guitar picks (Sovereign Citizen) revoke worldy government by Ultraviolet Produciton House

Can you tell me about UV Production House?

Ultraviolet Production House is an Etsy store. It shows images of potential or hypothetical art products. All of the artworks are composited through Photoshop and, upon purchase, the collectors receive five to six Amazon Prime boxes and a set of instructions over the course of two weeks. Then the collectors fabricate the work themselves.

It’s a location-independent, post-studio practice. My collaborator Brad Troemel and I can ostensibly do this project from a Starbucks or a WiFi-enabled McDonalds—anywhere that we can sit with our computers. We did a residency this summer called Work In Progress 2016 that was organized by Tiffany Zabludowicz. It was an office in the middle of Times Square, and the space was filled with artists for about three weeks. We heard about it on a Tuesday, and we were set up and working on Wednesday morning. So that’s just an illustration of how mobile and how adapted to the current economy/climate/landscape this project is.

Ultraviolet Production House has as low an overhead as possible. Most notably, that means there’s no studio expense—we don’t need to rent a space to work with materials and we don’t even need to do any material tests. We don’t front the cost for any of the materials that we include in our artworks, whereas when doing a physical show—or just autonomously producing work in a studio—you have to front the production costs for several thousands of dollars in material costs each time, and it’s a struggle to work out the right set of fabrication procedures. This project bypasses all of that. It is as close to a debt-free artistic practice as possible. It doesn’t require the artist to assume debt to produce the work, yet it’s still linked to objecthood.

Can you give me an example of a UV Production House artwork?

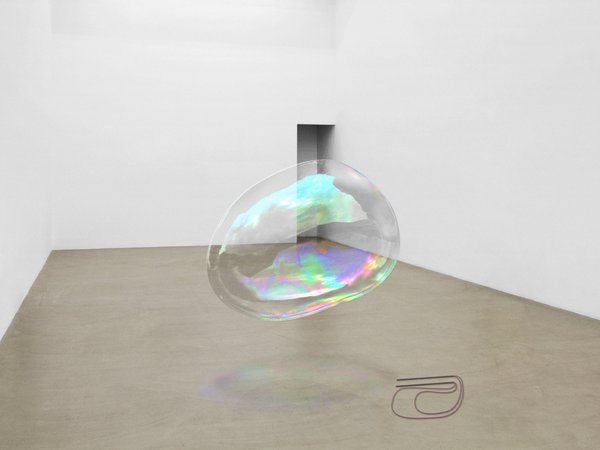

I think probably the most appropriate piece that’s available on the Ultraviolet Production House Etsy store is called a bubble. It’s a $100 piece available to buy off the Etsy store. And our model for valuing any of these artworks is just to double the materials cost. So we take a cut off of it, Etsy takes a cut off of it, and the cost is fronted by the collector at the end. So, with a bubble, the collector receives $50 of water, cornstarch, dish soap, and a wand. But the joke with this piece is that the volumetric characteristics of the bubble occupy space in a way that is precarious and temporary and can’t be shipped.

a bubble by Ultraviolet Production House

a bubble by Ultraviolet Production House

Do people buy artworks like these on Etsy?

Since we opened the store in late December of 2015, we’ve made 54 sales—which is 54 more than I thought it was going to be. The store ranges from pieces that are $15,000 to pieces that are $20. But the beauty is, if we don’t sell something, it’s not like we need to store it. If we were to actually produce these works in the studio, like say, the farm to table table, I’d need to store the table, and the chairs, and all the constituent materials that go into it.

farm to table table

farm to table table

Do buyers get a certificate of authenticity or anything?

Yeah, exactly. That’s the provenance—the certificate of authenticity. We even offer people the opportunity to leave the constituent elements for production in their original boxes, because they’re accompanied with a certificate of authenticity that still certifies them as the work. We like to call it the “unboxed mint condition Ultraviolet work”—because there’s always the possibility that, in the course of fabrication, the collector-now-fabricator could botch the production somehow. They could add a screw hole in the wrong place, maybe, or they could somehow mess it up and need to start over. It kind of inverts that power dynamic, right? We’ve now put the collector in the role of the fabricator.

And, if you keep the artwork boxed, it remains a collector’s item. They could flip a bubble if they wanted to, and resell it to another buyer. But if they fabricate the bubble, it’s not longer an investment. You can’t sell an already-made bubble.

Right. Everything in the store is double the cost of materials and not editioned. But the window of editioning is really the amount of time a project like this can remain on Etsy, and the store has been shut down four or five times now. So every time we update it, every time we make a sale, we go under review, and we’re under further and further scrutiny for really skating along the lines of the terms of service, because we don’t have any available or handmade inventory. After it goes down, potentially, all of those certificates of authenticity then flip the object. We tell curators and collectors that if you want to put this in a show you don’t need to email us and coordinate it—just buy it off the store. We would never tell you what to do with your own property.

Have any of the works been exhibited?

Yes. There was the Unbreakable Phone Case From Ballistics Gel at the “Re: Art Show” in Brooklyn, there was a project space in Aspen that exhibited several of the works, and Anonymous Gallery in Mexico City showed a work as well. Kayla Fanelli curated a show that had Justice Fedora: LED Anti Surveillance Hat anonymosa. It is fun for us when the works end up in a show and we get to see the install shots, because we’ve been anticipating the imagery without having had any experience with the material.

Do they end up looking different than the Photoshopped images?

The fabricated objects are pretty close to the initial images, which are photographs of the actual materials that are combined. They’re all drawn from product and stock photography. So, if we have a picture of a particular jar, we send that actual jar. We have made the perfect image prototype—the immutable, platonic form. There is the concept of the chair, the image of the chair, and then the materialization/fabrication of the chair, and they all refer to a more perfect version of each other.

Josh Citarella and Brad Troemel at Work in Progress Residency

Josh Citarella and Brad Troemel at Work in Progress Residency

You and Troemel were exhibiting artists before you started this project. Am I right to assume that the people buying these works on Etsy are people who already follow you and Troemel? Or do random people come across this project on their own and decide to engage?

There is only one person who bought a piece that we don’t otherwise know. We get the person’s name and address so we can ship it to them, and they usually write a little note about what they want to do with it, whether they want to put it in a show or in their collection. So, we generally know who is buying the work. There’s only one person who isn’t in the art world who bought a piece, though it was a $20 piece. Of the 54 sales, 53 of them were from collectors, curators, and other artists who want to support the project.

It’s a way for people to participate in a bazaar and experimental project. And it’s a very convenient way to ship work! It doesn’t require a lot of coordination—we don’t need an entire gallery team of assistants to do it. It’s also a way to compensate artists for their participation in a show. If I do a show at a commercial gallery, the compensation is the chance to sell the piece. I put it their retail space for the opportunity to sell it, not the guarantee. So the artist fronts the material cost and essentially assumes the risk in producing the object. Who knows if they sell or don’t? With our model, the piece sells before the work even gets shipped out, before any materials are even purchased.

It’s like art on-demand.

Right, it’s just-in-time production. The form is very much an alternative to the white cube. The content is maybe not as related. Right now we’re working on a PDF that will essentially be a text version of a talk that we give about the project, which we did at Aperature and Caroll/Fletcher in London. It’s kind of a studio visit for the project. One of the things we talk about is the native potential of the internet. The internet does a lot more than distribute images. The idea that “Post-Internet” means creating attractive images that look good on a screen is a very narrow view of the way that the internet has shifted art or the way that the internet is currently disrupting the conventions of the white cube. So something like Ultra Violet Production House, which sources the vast majority of the materials used to produce the objects, are sourced from Amazon. Since Amazon is already paying for the cost of storage, it becomes our free shipping service, too. We’re not just using the internet to distribute images, we’re also using these arterial distribution networks for the production of the object itself.

Through the model of Ultraviolet Production House, I now have every material in the world at my disposal and essentially in my studio. If it exists, it’s on the internet—and if it’s on the internet, you can buy it from someone. Also, whereas you normally might only be able to afford to produce something the size of a tabletop sculpture, you can prototype it through an image and put it up for sale. Once that’s approved, then you can produce the actual artwork.

Amazon Dash Punk Leather Jacket by Ultraviolet Production House

Amazon Dash Punk Leather Jacket by Ultraviolet Production House

And Etsy is another distribution network that you’re using that provides another art world function—it replaces the gallery, acts as the middleman, but it takes a much smaller cut. Do you think it’s possible to eventually and sustainably sell your work exclusively though Etsy? Or do you think artists will always need to rely on galleries to sell their work?

The answer is not yet. But is it possible? When I think about this project I think about Silicon Valley-style disruption and innovation frequently, and I think the question we’re posing here is, Could an online marketplace like Etsy displace the gallery system? Maybe not Etsy specifically… but it could be something else comparable. I will say that the brick-and-mortar gallery takes 50 percent of the artwork sale. Etsy takes three percent. That’s 47 percent preferable!

I was having a conversation with a good friend of mine who works at a lower-blue-chip or high-middle gallery and he was breaking down what funds the brick-and-mortar gallery—the primary market, the fairs, and the secondary market. My idea was that you could have a project space outside the major market circuit: Los Angeles, New York, London, et cetera. You could have a project space in Minneapolis, which is affordable with low overhead and has a good program, and you could go around to fairs to fund the rest of your year. You wouldn’t necessarily need to have a giant space, and you could take a lot more curatorial risks in your program. So with that model, you could get rid of the massive showroom that is the Chelsea art gallery. But my friend told me that these middle/high-end galleries are funded equally, in thirds, between the primary market, the secondary market, and the third being art fairs. So it doesn’t look like that is yet possible.

"Compression Artifacts" curated by Joshua Citarella

"Compression Artifacts" curated by Joshua Citarella

I would have thought that art fairs would have accounted for a bigger chunk.

I think for younger galleries it does. But when you’re brokering the sales of multimillion-dollar pieces every few years, even if it happens infrequently it becomes such a huge commission that it outweighs how the numbers break down. For younger galleries, the amount of stock they place in the fairs is much higher—maybe like two-thirds. It’s different for everyone obviously, and it depends on the individual space.

So since younger, smaller, emerging galleries make most of their profit from art fairs, they would be best suited to move out of New York, have less overhead, and like you said, fund their year at fairs. If this were to happen more and more, we have some pros and cons to consider from the perspective of the New York art community. The pro is that these galleries will be less constrained by the market and more able to experiment with their programming. The con is that New York will be striped of its most interesting programs, and emerging artists will have a tougher time showing in New York.

I think you’re suggesting something we’ve seen recently in articles about the erosion of the middle class in other spheres of the market. A similar thing is supposedly happening to the art market, where the people at the top are fine and the people at the bottom are still at the bottom. But it’s the middle-tier galleries that are having a difficult time scaling. They’re being pushed out of business.

The art market is this luxury market that is jettisoned from reality that’s on the bleeding edge of capitalism. It’s the very last thing to be disrupted because it’s the most highly coded of any market that exists. Yet, in succession, we’ve seen every facet of every market in some way be reorganized by networked culture. You’ll find clothing stores like Abercrombie & Fitch, Topshop, REI, et cetera, in places like SoHo and major shopping areas, in very expensive real estate. But what I’ve heard from people who work in that industry is that the stores themselves don’t actually make their rent. The point of having the brick-and-mortar store is to position the brand among other prestigious brands, and they make the majority of their sales through online shopping.

But it seems galleries haven’t been able to completely dispense from having the brick-and-mortar store. The overhead of having the physical space is a measure of a material, physical, and financial investment in how much they want to be a part of the system—a literal demonstration that you can put a metric on. But it’s really just about context. If everyone is on the same block in Chelsea, there’s a leveling affect where everyone is considered, at least by their address, the same. You have a gallery in Chelsea to illustrate the volume of your income.

And you can apply this logic to images on the web, too. If you go to an artist’s website and you see installation images that show giant, immaculate white cubes, you can assume that the artist is doing well—even if you don’t know what specific galleries they’re showing in or anything else about the artist. As artists, we understand that having our images circulate online is just as important—if not more important—than having people see our shows in person. But we still rely on the physical gallery space to give our work context and prestige, illustrated by the backdrop of the documentation photograph.

When I first found the foundation of my practice, it was forged in my experience of retouching for fine-art photographers who showed at galleries and museums in New York, and also documenting art installations in New York. So I did pre-production and post-production—both ends of the process. And in my experience of doing install documentation, I learned that art’s value is derived through context. So, on the level of the image, where you don’t have much context other than the space, the most effective way to make an object read as valuable is to depict it in a valuable space. If you’re shooting a smaller project space that has glass storefront, you’d photograph the work from outside so you could use a more telephoto lens where the perspective wasn’t warped and it didn’t look like a fisheye photograph of a small apartment. Instead you could make it look like a large space and imply that there was enough room to step back from the artwork.

"Compression Artifacts" curated by Joshua Citarella

"Compression Artifacts" curated by Joshua Citarella

You don’t have much to go off of based on the object, so for this kind of image that’s just circulating online, free of context, you have to describe the space as being valuable. Meaning you seal up the gap between the wall and the floor, you correct all the molding, all the lights, you make it the most beautiful architectural photograph as possible. The rules of install documentation are the rules of architectural photography, because you’re photographing a valuable space and that’s the only visual cue that the object is valuable unless you have its historical context.

This is a perfect segue to your “Compression Artifacts” project. Can you describe that for me?

Part of the experiment was to see if you could make a Hauser & Wirth in your parent’s backyard. “Compression Artifacts” is a gallery project that I did in 2013 that took place in an undisclosed location. I livestreamed the construction of an eight-foot-by-12-foot gallery space that was in the middle of the woods. I ran electricity out in the woods, it had lights, it looked like an immaculate white cube when it was photographed, but it was really just about $600 worth of material. I reached out to a number of people without having anything to promise them; I didn’t know what it was going to be. The people who agreed to go with me on this journey were Artie Vierkant, Wyatt Niehaus, Brad Troemel, Kate Steciw, and then there’s one of my own sculptures in the center. Then there’s a plethora of other objects that are alterations or edits of the physical objects they gave me, and combinations of works that end up being collaborations between, say Wyatt and Brad, that neither of them consented to—producing falsified hypothetical sculptures in Photoshop without the permission of the artists. This was all part of the work.

"Compression Artifacts" curated by Joshua Citarella

"Compression Artifacts" curated by Joshua Citarella

The experiment was to document the space and the installation extensively and then composite the white cube into a cavernous airplane hanger of a space‚ which worked in some circumstances and didn’t in others. You had to do the project to figure out if it would work. The linchpin of everything we’re talking about here—the bottleneck—is that we’re only looking at images of things. It’s rooted in a Post-Internet conversation. It expands to much more than that, but that's the beginning of it. Unless you show people before-and-afters, they’re willing to believe a lot from what they see. That's the census I got from this.

Though, if someone looks closely enough, they’ll see the clues that you’ve left in the images that make it clear that this space has been tampered with digitally.

There are a lot of incongruences and inconsistencies. But unless you see a very clear before and after, it’s confusing. It’s still a project that people are tremendously confused about. A lot of people are more satisfied thinking that I didn’t build the gallery in the first place and that this was a hoax. But it’s literally going to take just one generation of curators who grew up without needing a darkroom to make images and who are familiar with the tools of Photoshop and digital editing to understand that these artworks are clearly not only rendered. There’s a lens involved, and objects involved. I think it will be more familiar to them.

[related-works-module]