“In those days, what you would normally do is line up and the police might arrest one or two people, then they'd let you go, and later they'd close the bar down, and the bar would pay them off. But this time the patrons decided: 'No, we're not going to put up with that.' And that began this riot."

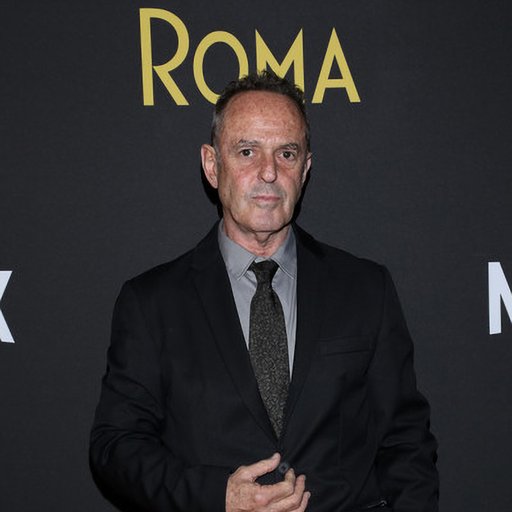

This is Jonathan Weinberg, painter and curator, describing the Stonewall Uprisings that broke out the night of June 28 th , 1969 at the Stonewall Inn—a popular gay bar in New York City that police raided, sparking a series of violent demonstrations by the LGBTQ community. "Art After Stonewall, 1969-1989" is the first major exhibition to examine the LGBTQ civil rights movement's impact on the art world. Co-curated by Jonathan Weinberg and Drew Sawyer (the Philip Leonian and Edith Rosenbaum Leonian Curator of Photography at the Brooklyn Museum), the exhibition is on view this summer in New York City at both the Leslie-Lohman Museum and the New York University Grey Art Gallery.

On the 50 th anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising, Weinberg and Sawyer met up with podcast host Amanda Schmitt to tour the Leslie-Lohman Museum and discuss the exhibit for the UNTITLED, ART Podcast. You can listen to the full episode here , or read our excerpt below—which includes a portion of their conversation about the concept of visibility, coming out, and how identity effects artists.

...

Amanda Schmitt: Can you describe this large, wraparound mural that we’re standing in front of—made of collaged elements, pulling from archival photographs from the 1960s?

Jonathan Weinberg: The mural is actually a large blown-up photograph of a mural that was in the Gay Activist Alliance building. It was this huge 40-foot collage mural. That building was burned down in 1974, not that long after the initial Stonewall riots, and they never discovered who burned it down.

Not that long after, the Gay Activist Alliance created this firehouse place. It was community place, it was a place where people danced again, and came together and organized, and somebody set it on fire. This mural celebrates not just gay pride, but it makes this connection to other civil rights movements—that gay rights were part of a larger civil rights movement that included feminists’ rights, women's rights, etc.

Courtesy of the Leslie-Lohman Museum, (c) Kristine Eudey, 2019.

Courtesy of the Leslie-Lohman Museum, (c) Kristine Eudey, 2019.

Drew Sawyer: One of the amazing things about Stonewall is that Tommy Lanigan-Schmidt and Marsha Johnson, two really key people who were at Stonewall, are both artists in their own ways. Tommy Lanigan-Schmidt is a visual artist, a sculptor, a writer and just an amazing figure. He was there at the moment and he's also in this photograph by Fred McDarrah, which is also in the mural. Tommy talks about how, for him, Stonewall was about two things. It was about just wanting to be able to dance together and the police wouldn't let us. The other thing he says is that when he's asked to remember it, he says it smelled like lighter fluid; I always think that's very evocative.

The other point that Lanigan-Schmidt makes is that middle-class white guys are often the face of gay liberation but the people who really fought in the front lines were people of color, transgender, or people of working class. He really wants to get that message across, because it's different from some of the media imagery that we see.

One of Lanigan-Schmidt’s sculptures is called Allegory of the Stonewall Riots (Statue of Liberty) Fighting for Drag Queen, Husband and Home (1969). The amazing thing about his pieces are that they're made out of tinfoil-like collage, and he takes things which you can find in your house and he magically remakes them, turning them into a chalice or into a little sculpture. He does that like an alchemist, and it’s very true to what the whole spirit of the LGBTQ world is like—you are given a kind of a difficult situation and you turn it into something beautiful and magical. That's really what these people were doing at the time.

Schmitt: So this piece is made out of foil, plastic wrap, pipe cleaners, linoleum, glitter, floor shine, food coloring, staples, wire, and magic marker. These are really objects that you can find in most houses, right?

Weinberg: Oh, yeah.

Sawyer: It's worth noting that there are two additional sculptures that are at the Gray Art Gallery. So some of the works that we'll see here, artists have other works at the second location.

Weinberg: But we really wanted Tommy to be in both places. He was actually at Stonewall, which is great. One of the other things to point out, particularly if you're not from New York, is that there were other riots that occurred in the '60s. It's not as if gay liberation began in 1969, but one of the reasons that Stonewall was so important was the decision to turn it into an anniversary, to have a march, to make images about it, to represent it, so artists really were crucial in that. So the fact that we remember Stonewall in a certain way makes it a turning point, and therefore it becomes a kind of rallying cry for the movement.

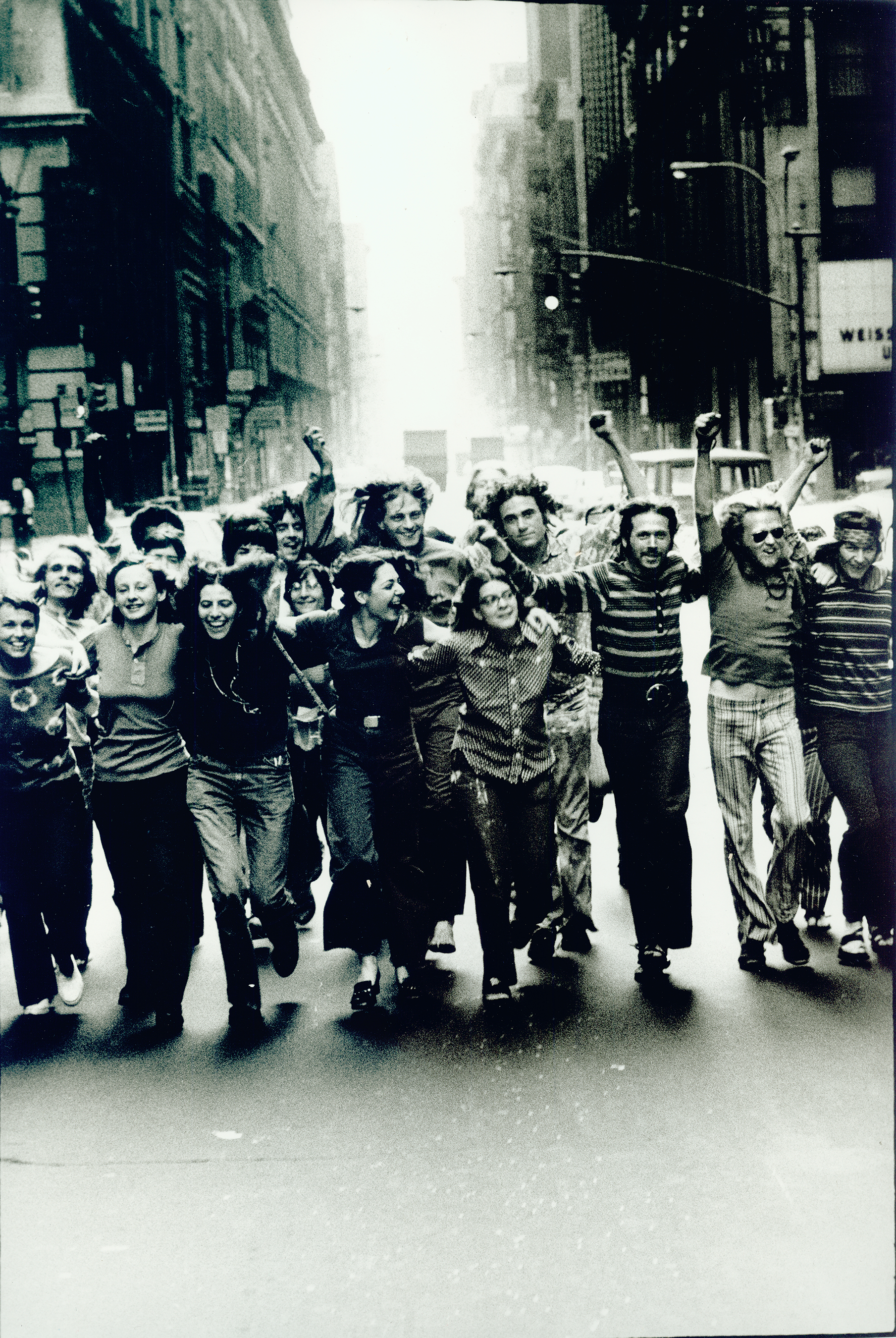

Sawyer: Right. And maybe we can talk about the Peter Hujar image, which shows a crowd of young individuals running through what looks like a downtown street in New York City in 1970, which then became the image for the poster “Come Out” that the Gay Liberation Front did in 1970, one year after the Stonewall riots. So again, Peter Hujar, a well-known photographer of the 1970s and 1980s, was like many other artist in the show, integral to visualizing the idea of coming out but also memorializing the Stonewall riots in the years following the event.

Peter Hujar,

Gay Liberation Front Poster

Image, 1970, Gift of the Peter Hujar Archive, LLC. Collection of Leslie-Lohman Museum.

Peter Hujar,

Gay Liberation Front Poster

Image, 1970, Gift of the Peter Hujar Archive, LLC. Collection of Leslie-Lohman Museum.

Schmitt: One thing that's interesting to me about this image is that it’s really one of pure joy, as opposed to the image of the riots that we were just looking at, or even imagining the night of Stonewall as filled with a lot of anger, fear, and terror.

Weinberg: I think that's a great point, because throughout the show, you see people having a lot of fun and there is joy. Even in the face of the most terrible situation, like the whole section on AIDS in the Gray Art Gallery, there's a great deal of anger, but often humor is used, employed as part of politics. I think they want it to be appealing to people. They want to grab their attention; to make them feel like they're taking over the streets, and taking over the city, and that this is a wonderful thing and not a scary thing. Because, depending on your privilege, coming out was a scary thing for a lot of people.

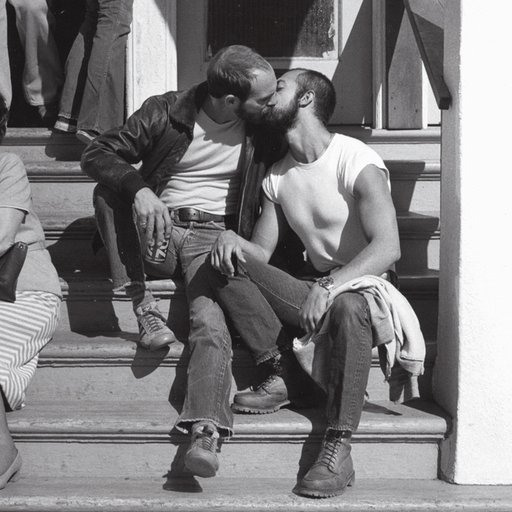

One of the things that we point out in the artwork label is that as wonderful as this image is, it's young, white people, who in some ways look like hippies. I don't know how much money they have, so I'm not going to discuss that aspect of it, but I have talked to people who were involved, and they were aware at the time that they wanted to be more diverse. They tried to get some African-Americans to be part of it, but the people who were involved at that time felt that it was too risky to come out. There can be an enormous difference between people's situations and what's at risk. Some people have to come out because they can't pass, just based on the way they act, or the way people see them. Those are the types of people that are often most bullied. And then other people have that ability to hide in plain view. This first section of the exhibition is meant to be very much about this idea of coming out and visibility.

Sawyer: In the essay accompanying the exhibit, I talk a lot about what comes along with the idea of coming out. It’s making oneself visible, but also, one's community. However problematic, as Jonathan was saying, this idea of community—especially when today we think of LGBTQ plus—there are so many contradictory or conflicting components within that, and certainly, many of the artists were aware of those.

Weinberg: Also, something that I think is really important, which Drew also talks about, is this idea of visibility. One of the things that makes this whole show different from a lot of ways of seeing earlier gay art, is that a lot of interpretations focus on the idea of repression or secret codes, so certain works of art by earlier artists may have a gay subtext. And the idea of the art historian, and the critic, is to figure that out.

But in so many works here, it's the exact opposite. The artists are showing you something. They're making things visible. And that's of course, what coming out is supposed to be about, it’s supposed to encourage other people to come out. And you can come out not just as a gay person; you can come out as somebody who's a friend of a gay person, or a mother of a gay person, or father of a gay person. And then the whole society, everybody's coming out.

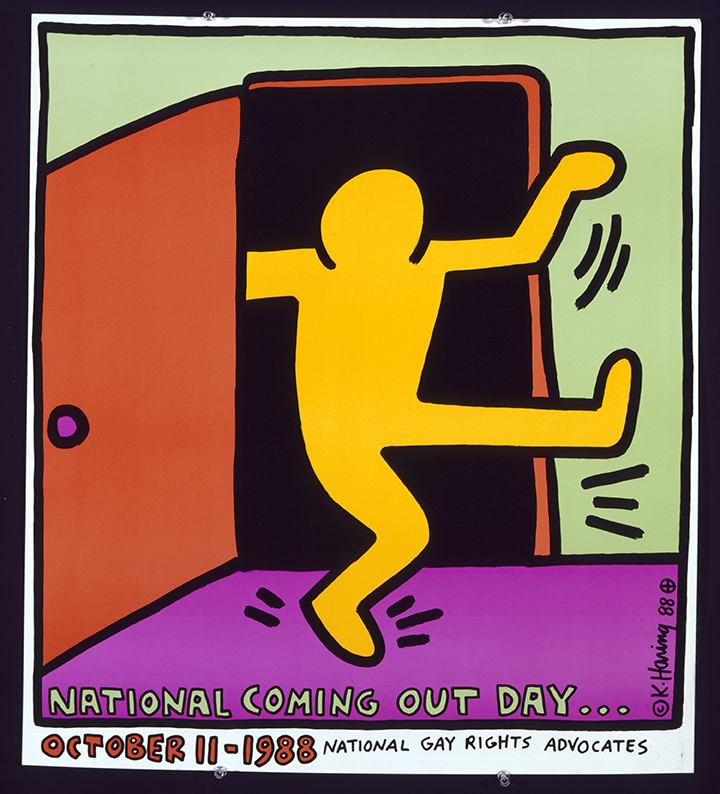

Keith Haring,

National Coming Out Day

, 1988. ©Keith Haring Foundation

Keith Haring,

National Coming Out Day

, 1988. ©Keith Haring Foundation

So this edition of a Keith Haring poster is for National Coming Out Day, which was happening in 1988, on October 11 th . It's a poster that, at least when I remember seeing it, you would see on college campuses in particular. There would be one day a year where different gay groups would really focus on trying to get people to come out and make it a particular day. This funny little yellow figure, sort of looks naked, but you can't see any genitals or anything, so it's a non-gendered figure that's coming out of the door, and there are these little marks that make it seem like it's a dance and it's all kind of happy. Like it's a joyous thing.

Sawyer: In a bright, multicolored room.

Weinberg: Right, in the cartoonish Keith Haring way.

Schmitt: I'm standing in front of a painting of a person with long, dark hair in a white blouse and they have this very intense stare, they're looking straight at me, and this is a painting by Alice Neel, called The Portrait of Kate Millett from 1970. Can you tell me more about this?

Weinberg: What's so exciting is that Kate Millett is the author of this groundbreaking, best-seller book Sexual Politics . This image was on the cover of Time magazine, and it was the woman's liberation issue. And it turns out that Kate Millett was very ambivalent about that, she didn't really want to be on the cover. She said she didn't want to represent all of the women's liberation movement, but nevertheless, that's how Time works, and Alice Neel is one of the great portrait artists of the 20th century. Normally she paints the subject directly, and doesn't like to paint from photographs, but this is one of the few examples where she did a portrait from a photograph. And she's really getting across that idea of strength, of Kate Millett as somebody who speaks from a kind of authority and anger too.

Sawyer: It's worth mentioning that this was on view at the National Portrait Gallery where it belongs, so it's amazing that we were also able to borrow this, because they had to take it off view from their galleries for this show and that tour, which is special. Many people maybe aren't aware that Kate Millett was also an artist. They may know her writing, but not her art.

Weinberg: Yes. It's one of the things that I think is astounding and speaks to prejudice, in some ways against women artists, and the way women are so marginalized. Here, you have such a famous figure in the history of feminism that was a practicing artist. Much of the last part of her career was just focusing on art making. She always continued to write. We have this major sculpture by her that hasn't been shown for almost 25 years, it's called Approaching Futility (1976). The work looks like a little jail cell made out of wood, and in the middle is a ladder, and on the ladder is a figure climbing up the ladder, kind of looking above, perhaps trying to escape or at least looking over the bars.

Courtesy of the Leslie-Lohman Museum, (c) Kristine Eudey, 2019.

Courtesy of the Leslie-Lohman Museum, (c) Kristine Eudey, 2019.

Schmitt: And I think it's important to note that this is human-sized, so it's not something miniature. I can really imagine if I were a person trapped inside of this cell, it would be quite claustrophobic.

Sawyer: Yeah. It barely fits inside the gallery it's so large.

Weinberg: Right. The original inspiration for the work was this terrible story of a woman named Sylvia Likens who was trapped in a house and brutally treated. It was a story that haunted Kate Millett, as a kind of metaphor or allegory for the way women in general are treated.

But I also love the piece in terms of the message of the overall show, because it speaks to how even when you're imprisoned, you can see through the bars. Even if you can't escape, you can imagine what your escape is like. Liberation doesn't happen all at once, it takes a very long time, and we're not actually free. There's another great photograph in the show that has a poster saying, “None of us are free until we're all free,” and that's always going to be something that is hard to accomplish... it's an ongoing process.

Another notion that I think is really important is the idea that coming out of the closet is not something you just do once, it's a process that you may have to repeat your whole life. For example, every time I talk on the phone to the cable company and mention my husband, I'm coming out to the person at the cable company. So I think that's another aspect of it—it's not a binary situation. You can be in your own prison, even when you're outside of jail.

Even now, there are many artists who are ambivalent about being known as an LGBTQ artist, and they'll talk about not wanting to be categorized. This is a big issue in feminism and other groups too, it’s often something that comes up in panel discussions—not wanting to be in a particular category as it can be very limiting. One of the artists who’s a fantastic artist in the show, Barkley Hendricks (he's in the Gray Gallery part of the exhibition), he's a black artist, and several years ago when I was doing a different show in a different context on photography, he told me that he had never been in a group show with major artists that wasn't a black artist show. My guess is that this is probably the first time his work has been put in a queer show. And this is a really important idea. He's straight-identified, but the work is two guys walking hand-in-hand whom he saw on the street, and he thought, 'wow, that's great, I'm going to make that into a painting.' So there are several works in the show by straight-identified artists, but where the subject relates to gay themes.

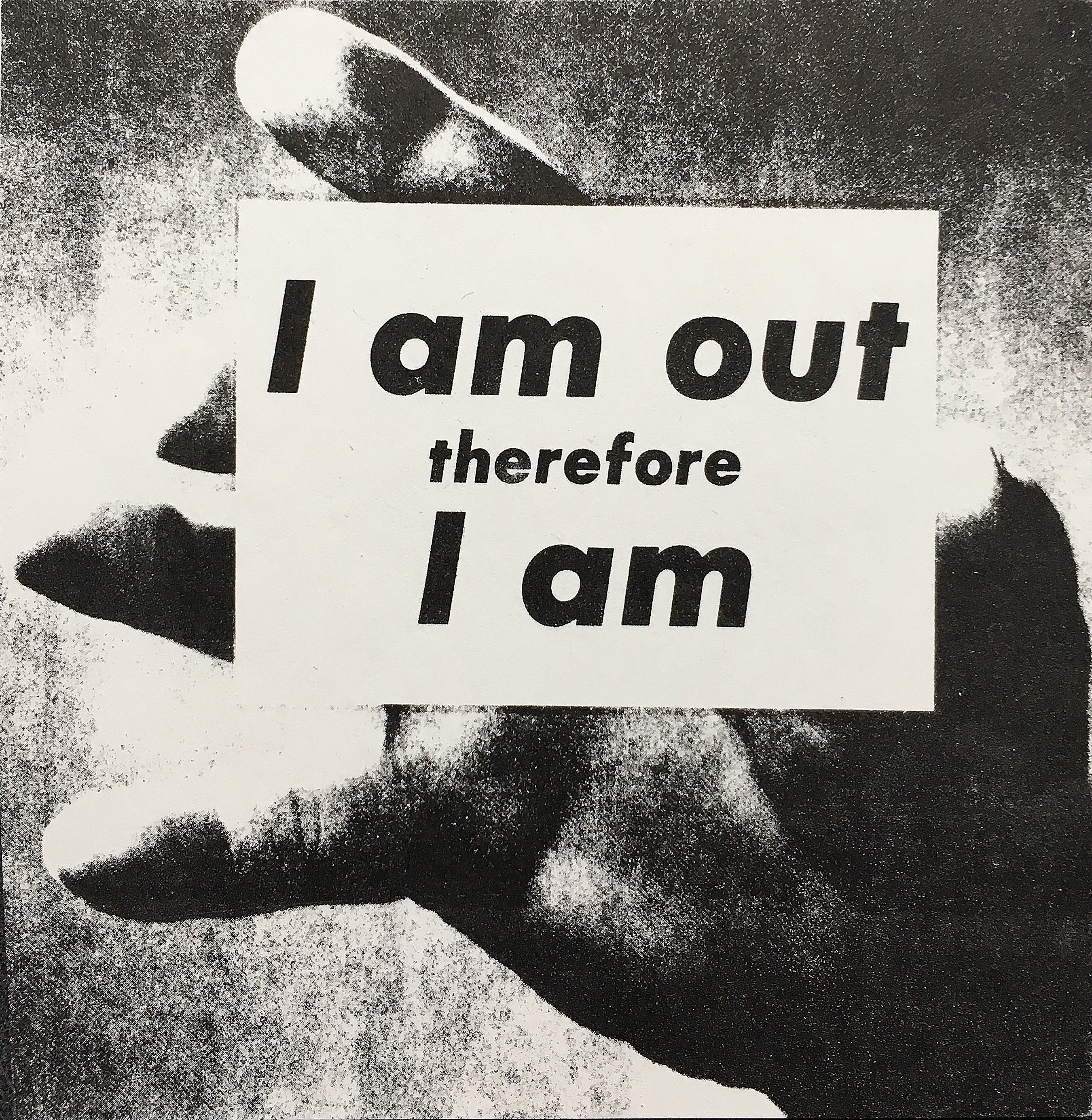

Adam Rolston,

I Am Out Therefore I Am

, 1989. © and courtesy the artist.

Adam Rolston,

I Am Out Therefore I Am

, 1989. © and courtesy the artist.

Schmitt: It's great stuff.

Sawyer: Right, and sometimes they're sort of borrowing from subcultures in the way that many contemporary artists working today do. People might use the word appropriation, or cultural appropriation, but in these cases artists were pulling from an emerging iconography within a certain subculture within their own images, and similarly pushing back against normative culture, so we have work by Adrian Piper...

Weinberg: ...Vito Acconci. Lynda Benglis...

Sawyer: ...Robert Morris.

Schmitt: I was actually interested in Vito Acconci's video Conversions from 1971. Is that here? Can we talk about that?

Weinberg: I interviewed Vito Acconci when I was working on my new book, Pier Groups . Vito Acconci has done amazing projects. One of the pieces that I was interviewing him about was this piece that he did in the abandoned piers along the waterfront, on Pier 17, where he would meet people out at one o'clock in the morning. If they would meet him in the middle of the night, he would tell them some secret, and they could blackmail him with that.

So Vito was very interested in, as you would say, crossing lines—normative lines, ideas of guilt, ideas of identity. In this particular piece called Conversions , he's trying to, in an almost violent way, take his body and turn himself into a woman. Or at least pull his skin into breasts, or burn his hair. It's quite a strange video, let's put it that way, like much of his work.

Schmitt: With this piece, you think of burning of hair and of course, you immediately think of what that might smell like…

Sawyer: Smell like, yeah.

Schmitt: ...the strong smell. And that brings me to this description you had earlier on, that many people who were at the Stonewall riots that night remember the smell of lighter fluid. I guess there's sort of a connection there.

Weinberg: You know, that's a really wonderful point. Because in a certain way, that is something that artists in the late 20th century (and young people even now) want to try to make the experience real and visceral.

Sawyer: A lot of the work we've been looking at so far is representational. We keep returning to this theme, which is about representation and visibility. So obviously photography and video were a huge part of making the movement visible, making communities visible, making oneself visible.

In a way, it sort of aligns really well to what artists are currently doing, which I think is also pushing against that idea of making oneself visible and all that comes with that; as Jonathan mentioned before, the feeling that one is being put into a category and that one has to perform their identity for an audience. Also, the way in which images, once they're out in the world, can be used for other purposes and the way that bodies can be used.

In the 1970s, and especially by the 1980s, you see artists increasingly exploring abstraction, but it doesn't mean the work is any less political. We could relate that to what's going on at the Whitney Biennial right now. Many critics have pointed out the degree to which the work is so formal, but that doesn't mean that the work is any less political, and most of it actually is. And I'm sure many of the artists would say that their work is deeply invested in the social and political, and that's true of Lula Mae Blocton’s work and a lot of the work that's in the second half of the exhibition too.

Weinberg: Artists back in the day, and now, struggle with the ways identity relates to their work. Is our work always about ourselves? Is every work a self-portrait? It is and it isn't. I feel that as a painter, I'm not making pictures that are just about me; I hope that they're about you. And if I make a painting that is about my own physical desire, does that limit the work?

If you're reading a book about miners who go down into the mine and dig for coal, is that only supposed to be of interest to people who dig for coal, or is their suffering possibly relatable to other forms of suffering that people have? The struggle for freedom is something that many different people share and it's relatable.

I always feel like the more specific a work is, the more universal it is somehow. The more that it comes from experience, the more relatable it is.

RELATED ARTICLES:

8 Iconic AIDS Activist Artworks that Changed the Trajectory of the Epidemic