Remember when painting was "dead"? This time it's photography that's been reported deceased. The digital revolution is the alleged killer, what with one billion images posted to the Internet every single day. The cause of death, appropriately enough for Daguerre's discovery, is overexposure. Photography is dead because it's all been done a million times; there's nothing new under the sun.

But photography does stagger on, however, just like all those corpses after a zombie apocalypse. Some of the walking dead are on display in the smart (and air-conditioned, and snack-bar-equipped) galleries at the International Center of Photography in a show titled "A Different Kind of Order," the latest ICP Triennial. The four curators of the exhibition, Joanna Lehan, Kristen Lubben, Christopher Phillips, and Carol Squiers, have assembled an international roster of 28 fine-art photographers who have managed to breathe life into the medium in a surprising number of ways.

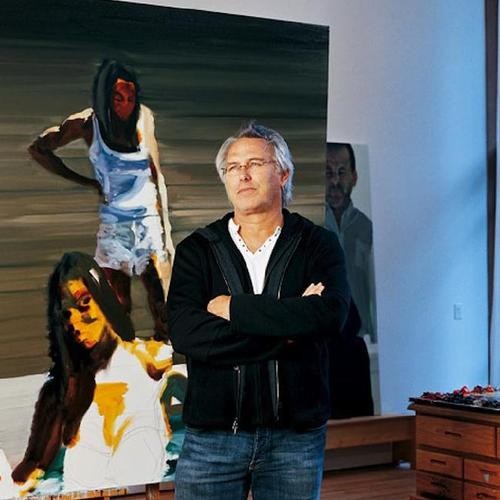

The biggest Dr. Frankenstein of them all—to further strain the metaphor—would have to be Los Angeles artist Elliott Hundley, who chops up what at first look to be snapshots of tiny gesticulating people and reassembles them into vast, densely detailed collages. He gives the works a fragile third dimension by impaling scores of even smaller photo-bits on a forest of metal pins of various lengths stuck into the work's surface, not unlike those used by bug collectors. Hundley shapes his constructions around a theatrical narrative, which in his contribution to the show is based on a play by Euripedes.

Elliott Hundley's Pentheus, 2010

Elliott Hundley's Pentheus, 2010

Collage, a pictorial strategy familiar from the dawn of 20th-century modernism, was the first and most literal destruction of the photograph, and as a result can seem to be rather shopworn. At the same time, there's nothing like obsolescence to put an image-making technique back on the avant-garde menu.

Digital technology has been especially hard on traditional photojournalism, which has suffered alongside the other media trades with the decline of the old-line publishing business. Many newspapers have cut back on staff photographers, for instance, relying instead on the big photo agencies or public-domain sources. It is citizen activists, armed with digital phones, Twitter, and Facebook, who do much of the news media's work today.

As a result, some photojournalists are trying their fortunes in the art world, and the ICP Triennial includes several such projects. The London-based, Johannesburg-born photographer Gideon Mendel supplies a lyrical video of handsome Africans wading through their flood-ravaged village, still waist-deep in water. The peek into other lives is fascinating, though the element of artifice—the scenes of colorfully dressed people posing somberly in the floodwaters are staged, I would guess—is unnecessary. The National Geographic Channel should hire this guy.

Gideon Mendel's Shopkeeper Suprarat Taddee, Chumchon Ruamjai Community, Bangkok, Thailand November 2011, 2011

Gideon Mendel's Shopkeeper Suprarat Taddee, Chumchon Ruamjai Community, Bangkok, Thailand November 2011, 2011

Another example is an impressive project documenting the huge, 54-story Ponte City building in Johannesburg, long a symbol of apartheid, which was originally developed as luxury residences but is now inhabited by more ordinary people. South African photographer Mikhael Subotzky and English-born photographer Patrick Waterhouse collaborated to assemble a remarkably thorough visual record of the tower via a triptych of orderly grids of color transparencies. These three photographic monoliths depict front doors, views from windows, and stills from the TV shows on in every single apartment—scenes that often include the residents in dramatic silhouettes.

Mikhael Subotzky & Patrick Waterhouse's Windows, Ponte City, 2008-2010 (detai)

Mikhael Subotzky & Patrick Waterhouse's Windows, Ponte City, 2008-2010 (detai)

Given the seismic impact that the Internet has had on the medium, it's no surprise that much of the work in the show mines this infinite image bank (rather than adding to it). Many artists don't make photographs anymore, they find them. They're re-animators.

Mishka Henner, a Belgian artist living in Manchester, scours Google Earth for scenic aerial city- and landscapes that include a section pixelated in a nice tortoiseshell pattern—a courtesy provided by Google to governments that want to hide defense or other secret facilities. In the gallery these camouflaged locales are blown up as largish color prints.

Mishka Henner's Unknown Site, Noordwijk San Zee, South Holland, 2001

Mishka Henner's Unknown Site, Noordwijk San Zee, South Holland, 2001

Similarly, the Vancouver artist Roy Arden presents a fast-moving slideshow of images taken from the Internet, organized alphabetically by Google search term: Delphine Seyrig, shoes, sofas, etc. Displayed on a smallish monitor in the corner, the work was supplied to the museum as a simple digital file.

More emotionally complex are installations of found videos or photographs taken in the heat of battle. For the Beirut-based artist, actor, and playwright Rabih Mroue, it's videos taken by citizen activists during the brutal civil war in Syria. The footage seems to show the videographers' final moments, as the combatant being filmed suddenly spots the documentarian, raises a gun, and shoots him (or her). The photographs are said to be the photographers' last as well, chronicling their own deaths. But are these scenes real or sophisticated propaganda? The question is addressed at length by the artist in an accompany video.

Rabih Mroue's Blow Up 4, 2012

Rabih Mroue's Blow Up 4, 2012

Similarly, the Swiss-born, Paris-based artist Thomas Hirschhorn has produced a harrowing slideshow projection of images of carnage—bodies literally blasted apart—from the Middle Eastern wars. He has put the jpgs on an iPad, and the video shows a pointing finger as it flips through the image files on the tablet. The inspiration for this technique, the artist says, comes from the pointing finger of St. John as he witnesses Christ's crucifixion in the Isenheim Altarpiece. Gruesome images of war-torn body parts are plentiful online, and Hirschhorn's selection includes no dead U.S. fighters.

Thomas Hirschhorn's Touching Reality, 2012

Thomas Hirschhorn's Touching Reality, 2012

These examples don't address the "death of photography," revolving rather around death plain and simple. But the ICP Triennial overall does demonstrate a common enough symptom of avant-garde esthetics, and that is a tendency to kill off the author—or at least put some kind of distance between the artist and the making of the work, substituting readymade found images or some variety of automatic image-making process. Particularly grim in this regard are the photographs of the Japanese artist Shimpeh Takeda, who doesn't use a camera or even light to make his photographs, which are composed of fields of black spotted with white, somewhat like a view inside a cosmic nebula. Takeda's method is to bury photographic paper with soil from Japanese sites of nuclear pollution, which produces his hauntingly simple images via deadly radiation.

Shimpei Takeda's Trace #7, Nihonmatsu Castle, 2012

Shimpei Takeda's Trace #7, Nihonmatsu Castle, 2012

When you go see the show, be sure to take a specially good look at the space. After 15 rent-free years, the landlord now wants market-value rent on the new lease: some $5 million per year. Chances are that, while photography will lurch onward, the end is near for the ICP's exhibition space (the school, located across the street, has a different landlord, and is profitable). Of course, given time, new ICP director Mark Robbins could work some magic, and the ICP museum could live once again. Stay tuned.

Walter Robinson is an art critic who was a contributor to Art in America (1980-1996) and founding editor of Artnet Magazine (1996-2012). He is also a painter whose work has been exhibited at Metro Pictures, Haunch of Venison, and other galleries; he currently has a new show on view at Dorian Grey Gallery in New York's East Village. Click here to see his previous See Here column on Artspace.