A week or so ago, I dropped by Fulton Ryder, the new by-invitation-only gallery, bookshop, and publishing headquarters established by the artist Richard Prince on East 78th Street. A devoted collector and bibliophile—as one might expect of a celebrated appropriationist who found his calling while working on the Time-Life clippings desk—Prince has on display rare, beat-era publications and ephemera, pulp paperbacks, and even a few copies of Art-Rite, the goofy newsprint art magazine I helped put out in the 1970s. Also available were new publications by Prince himself, including a recent hard-cover book reproducing some of the erotica posted online by the actor and out libertine Bob Crane.

My host was a young woman named Fabiola Alondra. She had previously worked for the much-liked Hamptons bookseller John MacWhinnie, who had collaborated with Prince on several projects over the years. After MacWhinnie's fatal snorkeling accident in January 2012, Prince had invited her to help him with Fulton Ryder. The relatively new organization has already hit the art-fair circuit with Prince's photo editions and books, most recently taking a room at the Lowell Hotel on East 63rd Street in conjunction with the AIPAD photo fair.

The name Fulton Ryder, Alondra informed me, is derived from the intersection of two streets in the Financial District. Fulton Street is famous, but Ryder's Alley? ("No one knows precisely who Ryder was," says the Forgotten New York website.) In any case, this imaginary personage is kin to another native of the Manhattan street grid, Kenmare Mott, a '70s pseudonym of the New York Neo-Dadaist Les Levine. He lived in Little Italy.

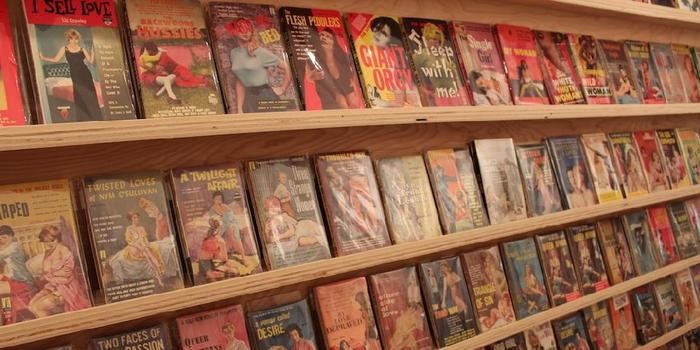

The primary attraction of my visit to Fulton Ryder was a substantial exhibition of new artworks by Prince. These works feature original paintings by pulp illustrators from the 1950s, each presented on the same expansive mat and in the same elegant frame as a copy of the vintage paperback bearing its reproduction on the cover. Here, Prince has brought "Found Art"—the title of show organized by dealer John Cheim for Robert Miller Gallery in 1980—to its avant-garde consummation.

Prince's framing technique—a form of collage that is not a collage, as Prince has described his photos of Marlboro cowboy ads—is a savvy move in the appropriation endgame. By presenting not copies but the original objects themselves, he sidesteps the copyright problems that have haunted him and so many other artists. What’s more, the “untitled originals,” as they are called, possess the kind of classical art virtues that academic postmodernism typically abjures—things like technical virtuosity, sincerity, melodrama, and popular narrative. These qualities can be viewed for their own sake, or taken with a certain amount of ironic distance.

The original pulp illustrations are more than covetable on their own, though, skillful enough to elude categorization as kitsch. In this case, the art market can be said to have outpaced the critical establishment, which has yet to embrace the pulp category: the auction record for the pin-up artist Gil Elvgren (1914-1980), for instance, is around $280,000. (Prince’s untitled originals are in this range as well.)

One additional conceit is that the fictional Ryder is also a writer, author of at least one equally fictional paperback whose cover bears one of the authentic period illustrations.

The Fulton Ryder publishing program includes not only the aforementioned book on Bob Crane (titled He Got It Coming and authored by John Dogg, another Prince alter ego) but also a slim paperback by Bill Powers—a kind of art-world roman à clef—that I have reviewed elsewhere. On my way out, Fabiola urged me to visit the new Upper East Side outpost of Powers's own Half Gallery, which is located right next door.

Originally dubbed "Half" by virtue of sharing its space with Diane Brown's nonprofit RxArt, the gallery has recently moved uptown after drawing hugely hip crowds for the shows at its Lower East Side storefront. I eventually found my way to the new digs during the unveiling of three-person exhibition. The avuncular Powers (who you may remember as a judge from Bravo's Work of Art: The Next Great Artist)was at the door, greeting visitors.

Located in a narrow brick building set back from sidewalk—Powers said it had once been the infamous love nest of "Girl in the Red Velvet Swing" architect Sanford White—the duplex gallery is upstairs from the boutique of Powers’s wife, the art-inclined designer Cynthia Rowley. All in all, a downright neighborly situation.

The show features works by Justin Aidan, Steven Parrino, and Blair Thurman, but what really caught my eye was a small sort of painting in the office—a rectangular object that had been smacked in the face, so to speak, by four gray pie tins filled with pigment, not whipped cream. Made by the 23-year-old New York artist Lucien Smith, the work was from a series that debuted last October at Jeanne Greenberg's Salon 94 booth at London's Frieze Art Fair. This example, which would be priced at around $6,000, was not for sale.

My first thought was: "painting as a pie in the face," a mash-up of Pop and Harold Rosenberg’s Action Painting. Powers added that curator Alison Gingeras had cited Julian Schnabel's plate paintings as a reference. In any case, Smith's studio vaudeville is certainly as much a Duchampian gesture as it is a Neo-Expressionist one.

Several years ago, in a New Yorker magazine profile, the inimitable artist David Hammons said to Peter Schjeldahl, “The less I do, the more it's art.” When it comes to the avant-garde, his observation is truer than ever.

Walter Robinson is an art critic who was a contributor to Art in America (1980-1996) and founding editor of Artnet Magazine (1996-2012). He is also a painter whose work has been exhibited at Metro Pictures, Haunch of Venison, and other galleries; he recently had a critically acclaimed show of new work on view at Dorian Grey Gallery in New York's East Village. Click here to see his previous See Here column on Artspace.