Given his body of work, it's easy to forget that multi-media artist Francis Alÿs isn't actually from Mexico. Originally from Belgium, the Flemish-born French speaking Alÿs moved to Mexico in 1986 as an architect on a three-year contract and by chance, ended up staying. It was in Mexico City that Alÿs began making art, mostly as a way to navigate and understand his new home, its people, and his own foreign-ness. His practice became one of public actions, video, painting, installation, and drawing, all used to articulate the bifurcations and boundaries imposed by politics and culture on society.

In the following interview with curator Russell Ferguson, taken from Phaidon's 2007 monograph, Alÿs discusses those early years in Mexico, how he identifies as a Belgo-European Mexican, and how his works helped him connect with and situate himself within his community as a local foreigner.

...

When did you first come to Mexico?

In February 1986, in the aftermath of the earthquake. Before that I had been studying and working as an architect in Venice. I was drafted by the Belgian army, and to fulfill that commitment I went to the south of Mexico to work as an architect for non-governmental organizations. In the summer of 1989, because of a number of personal and legal matters, I found myself stuck in Mexico City. My contract had ended and I couldn’t go back to Europe. Nor did I really want to. In front of me I suddenly had this enormous amount of free time, like an imposed sabbatical, and I decided to give a chance to something that had always interested me from an outsider’s point of view: art practice. Although by then I had been in Mexico for over three years, I had never really considered living here, and I found it quite difficult to accept the move. The first works—I wouldn’t call them works—my first images or interventions were very much a reaction to Mexico City itself, a means to situate myself in this colossal urban entity.

What was it about the city that was difficult for you compared to other cities?

The immensity of it, also the culture shock, I suppose, and how dysfunctional the whole thing seemed. I could not decipher the city’s codes. I had no entry point. In short, I could not understand how the whole society functioned. I had never lived in a megalopolis. Mexico City was also going through a series of major changes after the earthquake—in its urban shape, obviously, but also in its perception of itself.

Mexico City has a very crude and raw side, very much in your face, and it can easily beat you. When you are confronted with the dizzying complexity of a city whose nature is to overwhelm you, you have to react to that complexity somehow. I think the first stage was a period of observation, to see how other people managed to function within this urban chaos. I was living in the old Centro Histórico, where there were all these characters, for lack of a better world. I saw how they felt the need to make up an identity, to invent a role for themselves, a ritual that would justify their presence on the urban chessboard—like this guy in his mid-forties I would see every morning walking up and down the Zócalo with a metal wire bent into a hook with a circle at the end of it, kind of like a bicycle wheel without spokes. Starting from the top left corner of the plaza he would follow all the little cracks between the stones of the pavement, methodically pacing the entire plaza. That was the role he had invented for himself. That was his way of being there, of being part of the life of the city. Encountering such people has often been the entry point to my walks or interventions, the crude and poetic entry point.

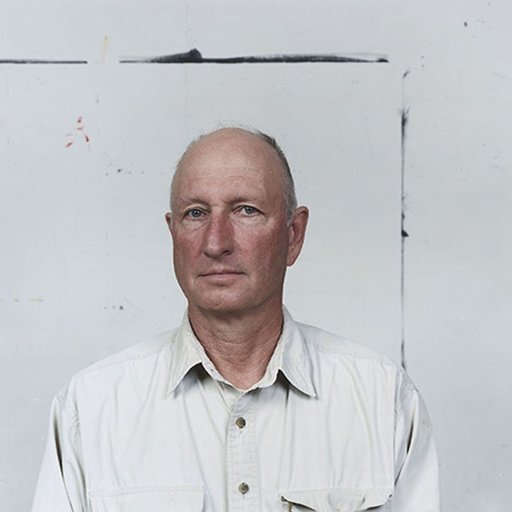

El Turista (1996). Image via pablo calderón salazar.

El Turista (1996). Image via pablo calderón salazar.

What did Mexico offer you that Europe didn’t?

Retrospectively, I think I was very lucky in my timing with Mexico. They say that certain people can only find their place within a specific historical or geopolitical context. There was something in the chemistry between my Belgo-European upbringing and the Mexican culture that triggered a whole field of investigation. I think also that my status as an immigrant freed me from my own cultural heritage—or my debt to it, if you like. It provided me with a kind of permanent disjunction, a filter between myself and my being. Maybe what I have been looking for since then is this moment of coincidence between the experience of living and the consciousness of existence. The city turned into an open laboratory for testing and playing and experimenting in all kinds of contradictory directions. I was new in town. Nobody cared. I had nothing to prove to anyone but myself. It gave me an enormous sense of freedom and an open-ended time frame to build a language, an attitude, away from a world and culture that I saw as saturated with information. I think Europe has an extraordinarily rich culture, but I see it more as a place of consumption—of arts, food, architecture and so on. Here there were things to do, things to say, and urgently. Eventually I lost the distance, but at first it was helped me make the jump.

At what point did you realize that you were not going to being an architect?

I worked in parallel as an architect and artist for a couple of years, but I dropped architecture altogether around 1993. I got hooked very quickly by the new game, the art game, and early on I met people like Ruben Bautista, Guillermo Santamarina, Cuahtémoc Medina, Gabriel Orozco, Abraham Cruzvillegas, Melanie Smith and many others. The contemporary art scene was very open at the time. There was a lot of collaboration and discussion going on. But then again, I was younger. Now I think the rules are different.

Do you think that individuals work in more isolation from each other now?

Well, there was no real market at the time. Artists were making art to show to their artist friends, and things were moving faster. You would not wait for a curator to come. You had to show it immediately.

There is a lot more infrastructure now.

The infrastructure is better, yes, and there is much more curiosity from abroad about the emerging scene, the younger generation, which is good. But it can also lead to some generational gaps, to the point that sometimes production can be aimed towards export rather than trying to function first in its context of fabrication, whether its local or national context. The link with the older generations is somewhat broken.

So now, after almost twenty years, to what extent are you a Mexican artist?

It’s clear that the place has imprinted itself on the making of my work and probably on the perception of my work abroad. Retrospectively I can see that there have been different steps in my relationship to Mexico.

When in 1994 I went and stood outside the cathedral next to the Zócalo with a sign at my feet saying “turista,” I was denouncing but also testing my own status, that of a foreigner, a gringo. “How far can I belong to this place? How much can I judge it? Am I a participant or just an observer?” By offering my services as a tourist in the middle of a line of carpenters and plumbers, I was oscillating between leisure and work, between contemplation and interference.

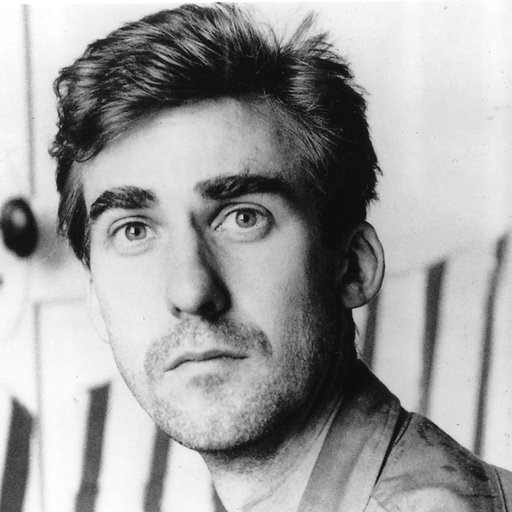

Paradox of Praxis 1 (1997). Image via Martha Garzon.

Paradox of Praxis 1 (1997). Image via Martha Garzon.

People do think of you as an artist from Mexico. How do you feel about representing the country?

I think I am quite local but I’m not. Or I’m not but I am. It’s a trap. It’s funny, you have to leave the place you come from to be asked if you belong to it. In 1998 when Rina Carvajal invited me to participate in the São Paulo Biennal, she asked a straightforward question: “How do you position yourself—as a European or Westerner—in relation to your host country, with the place and culture where you choose to live and develop your practice?” To address that issue I looked into one of the West’s most controversial exports, the model of modernization (as moving away from tradition), in order to analyse Mexico’s complex relationship to that imported ideology, and to investigate in particular how the syndrome of progress and the dogma of productivity are lived and understood south of the US border.

You referred once to your “disguise” as a foreigner. Did you feel you dropped the disguise at some point?

I wish I could, but I can’t. I am a misfit. I am too tall, too pale and too gringo looking. But things are not always that schematic. In the building where I live in the city center the population is very young. I have been around for much longer than most of them, so in a way, for them, beyond my foreignness I have become a sort of local reference. I suppose I may be even a character for some of them. When—very occasionally—a big-shot collector comes to visit the studio, he shows up in a limo with black smoked windows and two carloads of bodyguards. So, as everyone in the building deals some kind of shit, they must think I’m doing big-time deals for these big-time mafiosos to come here and visit me. So it gives me some kind of status in the hood after all.

And what came after Turista? You continued to work around the Zócalo, I know.

A couple of years later I put together a short film called If you are a typical spectator, what you are really doing is waiting for the accident to happen (nicknamed Bottle). I say “put together” because I went back to some discarded video footage, stuff I had kind of absentmindedly filmed on the Zócalo in early 1996, while I was waiting for the flag-raising ceremony to take place. It turned out that the material perfectly illustrated a preoccupation I had in mind. The camera was following an empty plastic bottle being blown around by the wind. There was to be no interaction between the camera (that is, me) and the protagonist (the bottle). The camera would just follow the bottle, record is dérive and wait for an accident to happen to it. Ultimately what happened turned out to be quite different. First, passers-by felt provoked or stimulated by the camera, and they started interacting with my subject, kicking the bottle around and jumping over it and so forth, and later on, as I was filming with my eye glued to the viewfinder, the bottle left the main square and crossed a busy street. As I followed it hastily, I was hit by a car—nothing dramatic, but hard enough to send the camera flying into the air and crashing on the ground. End of the take. I went back to that footage because I loved the fact that whereas one expects something to happen to the subject—the bottle—the accident actually happens to the observer of the bottle. The fact is that the act of observing had interfered with the course of things. My contemplative, non-interference contract was coming to an end.

So the bottle piece really marked a change in your status as an observer, from an outsider to someone a bit more directly involved.

Something new was triggered. On the one hand, as there had been a shift in my relationship to the place, I started to produce a series of works reflecting on the state of local politics. Cuentos Patrioticos (Patriotic Tales) (1997) was directly inspired by a political episode that had happened on the Zócalo in 1968, and its disguised re-enactment on the same location nearly thirty years later was a direct comment on the current state of politics, the way history was repeating itself, and how the whole political scene was frozen by a corrupted and dysfunctional political apparatus. On the other hand I continued questioning the mechanics of artistic production and the status of production itself with a piece called Paradox of Praxis 1 (1997). It was composed of two symmetrical, though opposing, principles: “sometimes making something leads to nothing” and “sometimes making nothing leads to something.”

In parallel I started working on my first animated movie, Song for Lupita (1998), in which a woman endlessly pours water from one glass into another and back. I wanted to demonstrate the Mexican saying “el hacerlo sin hacerlo, el no hacerlo pero haciendo”—literally “the doing but without doing, the not doing but doing.” It staged a kind of resignation to the immediate present by inducing a complete hypnosis in the act itself, and act which was pure flux, without beginning or end.

Animation is all about timing, and I think it was around this moment that I realized that Latin America’s relationship to modernity and the dogma of efficiency could be explored from that angle. I understood that through films, events or performances the mise en scéne of certain time schemes could render the time structure I had encountered here in Mexico. From then on I started developing what would become over the following years a discursive argument composed of episodes, allegories or parables that staged that experience of time.

One of the things that seems very characteristic about Mexico City—at least from the outside—is a constant pushing back and forth between the embrace of modernity and a resistance to it.

It probably happens in other places too, but this is the one I know the best. It seems particularly palpable in this part of town, the old city center with all its anachronisms. Its three layers—pre-Hispanic, colonial and modern—co-exist more than overlap, I think you could say that all the ingredients are present for Mexico to enter modernity, but there is this inner resistance. Somehow it’s a society that wants to stay in an indeterminate sphere of action as a way of defining itself against the imposition of modernity.

It’s this capacity of flirting with modernity without giving in that fascinates me. I suppose that in our age of the global market economy you could argue about whether that modernity was ever even achieved. But what matters now is the memory of it, whether it was a reality or a fiction. You can have a nostalgia for something that never really happened.

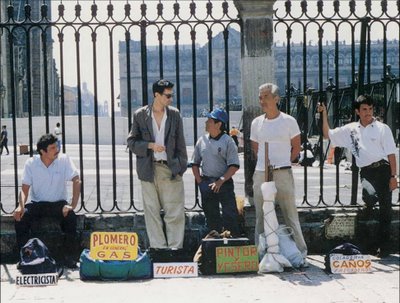

Sleepers (1999-2006). Image via The Red List.

Sleepers (1999-2006). Image via The Red List.

I noticed a cartoon pinned to your studio wall with an old man saying, “Of course, it was a long time ago, but at the time it seemed like the present.” [laughs]

I think there is a whole aspect of my practice that just tries to deal with all these anachronisms, to represent and to document them. I have seen some urban activities disappear from one day to another because of a radical change in city policies. When I first went to Lima, the Old Centre was very much like the Centre here, with street sellers everywhere. A year later there was not one street seller to be found. From one visit to another a whole culture had been wiped out. What I am saying, simply, is that to have witnessed those kinds of drastic evolutions in the life of a city makes you want to document more systematically the manifestations of these parallel, informal economies that are the obligatory components of the Latin American megalopolis.

The style of the documentation series is influenced by August Sander’s People of the Twentieth Century or the eighteenth-century prints Cries of London. My method of shooting is always systematic and tries to respond technically to the encountered situations. Sleepers (1999-2006) will always have the camera at ground level. Beggars (2002-04) takes a quasi-hypocritical high viewpoint. Ambulantes (1992-2006) is always shot perpendicularly to the passing subject at a distance of five metres or so. In that sense it is as neutral a register as can be, and it is that which might give it its archival value over time.

You once referred to yourself as “a former European.” Earlier I asked if you were a Mexican artist. Are you a Belgian artist in any sense?

As you know, since you are Scottish, Belgium has certain imprints that you can’t wash away. And being a Flemish-born French speaker doesn’t help.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Nine Totally Badass Latina Artists in the Hammer's "Radical Women" Show

Make America Mexico Again: 10 Artworks About Immigration and the Border

Mexico City's Lulu Project Space Brings Global Energy to the Latin American Cultural Capital