In art historian Gavin Butt’s introduction of his 2005 text Between You and Me: Queer Disclosures in the New York Art World, 1948-1963 , he quotes John Giorno, who thinks of gossip as “the hardcore of art history”:

“Unlike art criticism, which [John Giorno] accuses of being ultimately an instrumental discourse serving the interests of the art market, he takes art-world gossip as witnessing the real things which affect artists’ lives and the making of their art: 'I think who’s fucking who is where it’s at… And all the neurotic paint between people, which has some effect on their work.'”

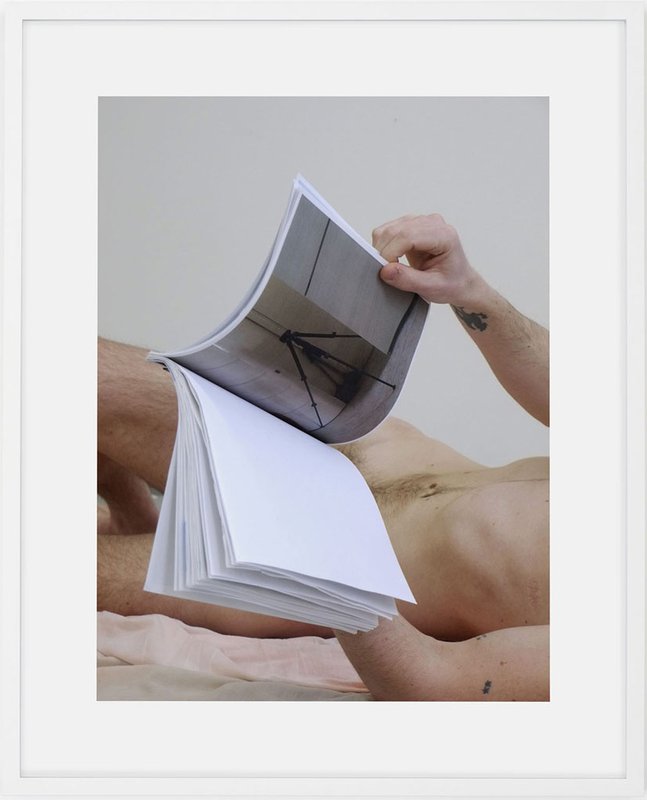

While the social relationships between young, gay men in the artist’s social circle are literally the subjects of Paul Mpagi Sepuya’s photographs, the formal aspects of the work are often what receives the most attention—which isn’t unsurprising considering Sepuya's innovations in the field of photography. Formally speaking, Sepuya makes images by photographing his subjects, or parts of his subjects, amidst mirrors, printed photographs (or parts of them), and drapery, creating a fractured image that folds foreground and background, living subject and documented subject, the current moment and past moments, into a single plane.

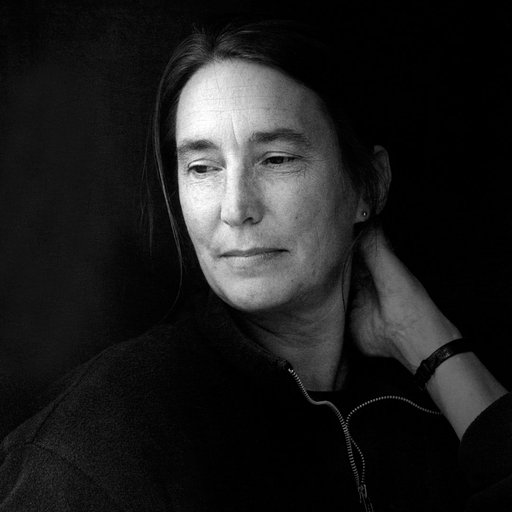

But while Sepuya’s formal strategies are, on their own, worthy of praise, let’s not forget what Giorno said about “the real things which affect artists’ lives and the making of their art”—and the potential for "real things" to add meaning and context to an artist's project. Sepuya’s photographs involve a revolving cast of friends, the majority of whom are gay men, and the interpersonal conditions that Sepuya sets up in his studio become performative—a reflection of how the boundaries between friendship and lust are not always clearly defined, at least not in the queer social space in which Sepuya operates. Here Artspace’s editor-in-chief Loney Abrams speaks with Sepuya about his work, but also about those juicy details that are too often left out of art history in favor of formal criticism and discourse.

You got your MFA from University of California, Los Angeles in 2016, and right away got swept up in the storm. In 2017 alone you had three solo shows, a three-person show with Deana Lawson and Judy Linn at Sikkema Jenkins , you were in the "Trigger" show about gender at the New Museum in addition to being in eight other groups shows, I’ve seen you all over the fairs—and you’ll be in a show called “Being: New Photography 2018” at MoMA opening in March. Were you expecting this kinda of attention right out of the gate?

Well, I’ve been working for the last seven years so it's not like I’ve just gotten started. A lot of really amazing stuff has happened over the past year but it's interesting sometimes the way that things like to be headlined or whatever—like "new artist to watch out for"—but I've been around for a long time! Grad school did offer a chance to reevaluate and reassess what I was doing, though, and having the two years to spend back in California gave me distance from New York, which was important. I'd been making work so tied to New York, not in that it was about New York specifically, but it was tied to a social space there. It was helpful to move and get a different perspective, and to also have a studio space.

You didn't have one in New York?

I think it's pretty common for people who do photography or who are in grad school that the process is very much: camera, to lab or darkroom, to portfolio or wall. Studios don’t necessarily need to be part of that. So having residencies at the Center for Photography at Woodstock and the Studio Museum in Harlem really expanded the possibilities of what a studio could be for me. But other than during those times, I was always in and out of studio spaces, just because it's so unaffordable in New York.

Darkroom Mirror Study (0x5A1525)

, 2017. Image courtesy of Team gallery

Darkroom Mirror Study (0x5A1525)

, 2017. Image courtesy of Team gallery

The promo image for the New Museum show (“Tigger: Gender as a Tool and a Weapon”) was one of your works. You also had a piece in that show that was a table installation with laser prints, artist books, postcards, and other ephemera. Can you tell me a little bit about that piece?

That's an ongoing project called Some Recent Pictures that began in 2011 when I last had a studio in New York. I was trying to think about what the boundaries of a studio or a portrait-based practice could be. I was traveling a lot then so I just let myself be more free from the more rigid, formal portraits I was making and began to gather material in a very loose way. I also didn't have access to a dark room at that time, so I began printing using a cheap laser printer from Staples. That material became stacked papers which would become shuffled and edited into these binder-clipped book bundles that would live on my kitchen table, or in my tote bag, or in my friends homes. So it became a way of generating materials, which I still pull from today.

I started working on how to edit the first volume starting in 2013 at the Fire Island Artist Residency. I believe volumes four and five are at the New Museum installation. The tables are used as a way of making a fixed installation, where the contents from the studio are made into an arrangement not based on some sort of past configuration of social relations but remade based on what I'm currently working on and maybe my current relationships to the subjects. So what's on the table underneath the books is material from my studio, work prints, excerpts of things that might fall into the next volumes of books, etc.

RELATED ARTICLE:

New Museum's "Trigger" Curator Johanna Burton Discusses Her Mixed Reviews in the Wake o #MeToo

You’re using a lot of those things in your flat photographs as well. When they're laid out on in the table it seems there's more of a focus on these individual images and subjects; they represent particular moments. When they're used in your photographs, however, they feel like they're more symbolic and referential, rather than representational. A photograph is often described as capturing a single moment in time. But what I think is so fresh about your work, is that you’re using photography to collapse all of these disperate times and subjects into one flat image. You're using collage elements, parts of photographs that you've taken before, found photographs, mirrors—so it seems to me like there's a narrative, not a linear narrative, but more of a timeless narrative that conflates different moments.

Is there also another kind of narrative that's going on that a normal viewer might not pick up on just because we don't know who these friends, partners, artists are? Is there another story to uncover?

There's really never a linear narrative. One could say there's an accumulative narrative in terms of the amount of information being given. A lot of it plays off of what is required in recognition. So I acknowledge that there's a lot that can only be read to an inside group. It could be something as casual and fun as people being able to recognize fragments of themselves or their friends in the work.

Study For An Exchange JO with four Figures

(2015). Courtesy of Yancey Richardson Gallery and the artist.

Study For An Exchange JO with four Figures

(2015). Courtesy of Yancey Richardson Gallery and the artist.

By using collage elements and reflections, the space in your images is formally broken up in a way that, for the viewer, can be very difficult to parse. When you're looking at it, it takes some work to really figure out what you're looking at and how it's all put together. And in figuring out where your perspective is coming from as a viewer, you become kind of destabilized or disoriented in regards to your own role and relationship to the work. Do you see the fragmented nature of your work, and the destabilizing nature of viewing the work, as having a relationship to the nature of gender and sexuality in general? In other words, are you somehow commenting on the fluidity or fragmented nature of gender and sexuality?

Oh, yeah. One could say it’s tangentially related to gender. But it’s not a direct comment or critique in the work. But yes, in some sense any of the formal elements, or how the image is constructed, directly respond to the realities and complications that arise from the production of portrait-based works that are very intimate. I’m playing with disclosure and concealment, and the ways in which images function as they get dislodged through the internet or through duplication and distribution. I’m always interested in having to leave behind the boundaries of what's considered art or not. So I used the mirrors initially to be able to reconstitute, in a single image, certain subjects or contents that were dispersed linearly across the book bungles, and as a way to think about the studio as a recurring ground that's always slightly changing. The fragments of portraits and studio comes from my interest in the queer, social, creative, and erotic exchanges that all happens in the process; in these places, nothing gets defined in a particular category.

Let's talk about desire, a central theme in your work. Photography in general is inherently about desire, in a way. It's always objectifying subjects for the viewer. You appear in your work as a subject at times. So the roles of photographer verses subject, and the desired and the desiring are mutable. How do you define desire? You’re work is homoerotic, but is desire always sexual? Or is it also something that’s inherent to the medium, or to art in general?

I don't think desire can be separated from vision, and I don't think it can be separated from photography regardless of whether or not there is a human body in the photograph. It’s not just about sexual lust. The surfaces and mirrors that I use reference an art historical, vernacular historical, or contemporary reference that assert the importance of desire in photography. Photography is a technology that produces for us images that wish to be seen. Photographs wouldn't exist if we didn't desire them to, whether that desire comes from lust or curiosity.

How have your individual relationships with your subjects influenced the way you treat them visually? How do you decide whether to show someone's face or just their body parts? Who do you photograph in the nude and who do you photograph clothed?

I started off photographing everyone—regardless of the nature of the relationship—as if they were a lover or a partner. I was starting that work in 2005 when I was forming a whole new social circle, not knowing that these people would become my closest friends a dozen years later. So it started off as a way to create an undefined state of relationships, but while acknowledging the fact that there's a certain sense of desire in the formation of these relationships—particularly so in a queer space, surrounding mostly gay men. There are very slippery boundaries between the platonic, romantic, and sexual—everything can be held in a state of suspension. So that's where that started, and at that same time I stopped photographing strangers and models. All of my subjects were determined by whether someone was interested in the project, or whether someone was comfortable in being revealed or not.

And then there’s a difference between the photograph that gets made and the editing or selection of a particular image for an exhibition. So you might just see a fragment of someone in a particular show but there's a full portrait of them somewhere else, which I think should be kept in mind—along with the fact that most of the subjects are also involved in the production of art or writing or music. Sometimes my work nods outside of my world towards their work or the world that they're in. But again that's only information that someone on the inside would know. When I write statements I tend to talk about the formal structures, rather than talking about individual stories.

Can you tell me about the most intimate experience and also the most awkward or uncomfortable experience you've had while shooting these images?

I stopped photographing strangers because of several uncomfortable situations. There's so much fantasy brought to play in making these things. The platform a photographer creates is something I'm very conscious of, but it becomes a stage for people to act out their own preconceived narratives. But otherwise, not really.

Are your subjects often people that you're dating?

Sometimes, but usually not. No, they're the friends I go rock climbing wth or have dinner with or meet at house parties. But they all acknowledging that in a certain sense, the nature of friendship, and of looking, and of the production of artwork—is erotic. So it's often a play off the idea of mutual interest—mutual desire, objectification, or scopophilia that’s inherent to the whole process.

Mirror Study (_Q5A3505)

, 2014. Courtesy of Yancey Richardson gallery and the artist.

Mirror Study (_Q5A3505)

, 2014. Courtesy of Yancey Richardson gallery and the artist.

You mentioned that many of your initial subjects became close friends over the years. For you, how has the meaning of your work changed over time as your relationships to your subjects change?

I sometimes look back and see some things in a portrait that I didn't see initially. When I decided to focus on this project, I had one set of things I wanted to get out of the photoshoots: a clear, sharp image that helped me define my relationship to that person. I followed my own needs in attaining that, but in some cases, I probably wasn’t actually tuning into what that friend was carrying with them or dealing with, or I wasn’t taking into account why they accepted or declined sitting for a portrait. Now some of those friends look at older images and they might say, “This portrait is very hard for me to look at because of the stuff that was going on in my life at that time.” At the age of 23, I wasn't aware of these things. So in a sense, I do feel more aware or mature now about some of those past friendships. Over the course of the project I’ve lost touch with some people, reconnected with others, and there’s one person who I’m no longer friends with at all. But it’s not like there are certain works that I just don’t like anymore.

I imagine it could be strange for some of your subjects because unlike traditional portraiture, which is often tries to distill the essence of person into an image, your images are less about the individual and more about formal relationships and personal relationships in an abstract sense. I mean in some cases you’re literally ripping the arms off of people. You’re ripping things apart to make a new whole that isn’t necessarily representative of one individual person or even one individual moment in time.

Yeah.

To wrap up: is there anything that you have coming up that you're excited about?

I'm doing a talk (along with a screening) with my friend A.L. Steiner on January 18th at the New Museum; it's part of the “Trigger…” show. After that, there's a group show coming up in February that Nayland Blake has curated at the ICA in Philadelphia [called “Tag: Proposals on Queer Play and the Ways Forward"]. And then the “Being: New Photography 2018” show at MoMA in March.

Exciting!

[related-works-module]