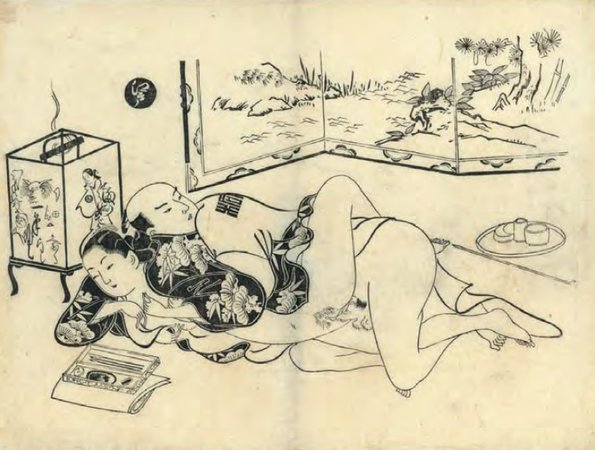

After more than piquing our interest in historical Japanese erotica, we're taking a second, more intimate look at the history and influences behind these unique, beautiful, and evocative prints (called shunga, or "images of spring") and the hedonistic ukiyo-e (meaning "Floating World") they depict. With a legacy spanning centuries and an impressive catalogue of artists, Japanese erotic art not only represents forms of pleasure often suppressed in polite society but also points to the country's changing political tides.

Excerpted from Phaidon'sPoem of the Pillow and Other Stories, this introductory essay by the scholar Gian Carlo Calza takes us behind the painted screens of the pleasure quarters and deep into the complex history that surrounds them.

The Japanese erotic paintings and prints called “images of spring” (shunga) play a far richer and more complex role in the country’s wider artistic context, compared to the situation in the West, where this art form has often been perceived as a form of sinful expression or even as morally corrupting. This, however, was not the case of the nude. In the West, the Greco-Roman tradition made the beauty of the unclothed body an object of worship, something that did not happen in Japan.

On the other hand, the Christian concept of original sin, with the consequent repression of sexuality, means that traditionally we find ourselves caught between the exaltation of the nude and the condemnation of the sexual act when not associated with procreation. The nude, moreover, is not appreciated for itself, but primarily as something connected with an iconography derived from Greco-Roman classicism, while sex, even when depicted in art, has always been seen in a negative light.

In the West, therefore, the nude represented in the classical manner became an elevated art form, but it also offered a legitimate opportunity to look at naked bodies—an activity that otherwise had for centuries been seen as the gateway to sin and perdition. Japan, in contrast, lacking as it does both the tradition of contemplating the naked body and the association of sex with sin, witnessed the prolific production of great erotic art by important artists, but did not include the nude as such.

This does not mean that the naked body is not represented at all in Japanese art; rather, its presence is not an end in itself and is dependent on the context of the print or painting. Nudes, therefore, whether total or partial, are not portrayed to be contemplated for themselves but have a functional purpose: as carriers of palanquins wading across a river, as attendants or guests at public or private baths, or while performing ritual ablutions under a waterfall or, of course, while engaged in sexual activity.

As represented in Japanese art, sexual activity hardly ever originates from routine situations such as a married couple making love naked in the heat of summer, but rather springs from transgressive circumstances: a clandestine encounter, a fleeting moment of intimacy seized upon during an excursion, when a lover can sneak in while the legitimate partner has fallen asleep, or when a man takes a sleeping young woman by surprise. Rarely, therefore, is the image of the nude associated with eroticism. This is the case of the painting by Utamaro of a naked woman stepping into a bathtub, currently in the collection of the MOA Museum of Art in Atami, where the image is indeed provocative but is hardly sexually meaningful.

Furthermore, and especially in the making of prints (which enjoyed far wider circulation than paintings), there were very close connections between the world of publishing and its artists, the world of textiles and its craftsmen and clothing manufacturers, and the world of the grand courtesans who were portrayed on thousands of occasions in ever-changing attires. While this was not, of course, the determining factor for the choice of the subject matter, it should not be underestimated as an influence on the choice of items used to embellish a picture. As a consequence, since it was necessary to clothe the people engaged in sexual activities as well as to depict their furnishings and interiors, a kind of publicity service was frequently created among manufacturers, artists, publishers, and the owners of teahouses.

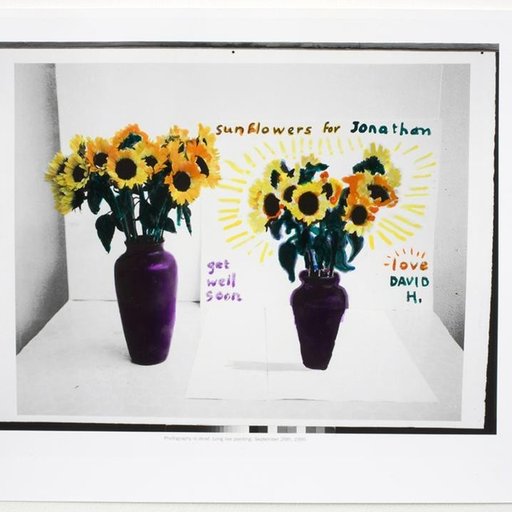

Scene from Torii Kiyonobu I Erotic Contest of Flowers, c.1710

Scene from Torii Kiyonobu I Erotic Contest of Flowers, c.1710

The production of erotic images is documented, in literature at least, as early as the Heian period (794–1185), when it appears to have been popular among court aristocracy and in temples. The earliest paintings date back to the end of the Heian and the beginning of the Kamakura period (1185–1333). These are, however, copies of even earlier works, of which the originals have been lost, such as The Illustrated Tale of Koshibagaki (Koshibagakizōshi ekotoba), which illustrates the story of a notorious scandal at the end of the tenth century, where a liaison between an imperial princess and a captain of the Imperial Guards took place at the Ise temple where she was performing purifying ablutions.

Another example is The Illustrated Tale of Chigo (Chigozōshi ekotoba), which tells the story of a beautiful young boy who worked in a temple in the imperial city and ended up having sexual relations with all the monks. A third, entitled The Illustrated Tale of the Monk in a Bag (Fukuro hōshi ekotoba) tells of a young monk who tried to seduce two young women, but, having been enclosed inside a bag, was forced to satisfy one woman after the other until he was totally exhausted.

Work of this kind continued to be produced throughout the following centuries, but very few examples are known. It was an era of austere social values, ruled not by the aristocracy of the court, but by that of the sword, and by the neo-Confucian morality with its restrictive code of behavior. It is quite likely, however, that with today’s changed attitudes towards this kind of art, hitherto unseen works will emerge from centuries of oblivion.

From the seventeenth century, things changed radically and the production of erotic images seemed to have increased exponentially. This phenomenon was due not so much to a relaxation in the codes of behavior—which were in fact periodically renewed and reinforced—as to the expansion of the new urban and middle-class culture for which Edo, modern-day Tokyo, became the epicenter of the whole nation.

Originally no more than a village, in the space of a few decades Edo had become the largest metropolis in the world, with a population of approximately one million at the beginning of the eighteenth century. In 1600 Tokugawa Ieyasu, the feudal lord who had made it his capital, had subjugated the whole of Japan after 150 years of civil wars. In 1603, he had established the Tokugawa shogunate and, having assumed the title of shogun, the country’s highest political, administrative, and military authority, he reorganized the feudal system, keeping the emperor at the apex of every power structure if only symbolically, including the country’s religious hierarchy.

The city expanded at an astonishing rate, partly due to the forced residence there of the 260 or so feudal lords, the daimyō. This system enabled the Tokugawa shogun who succeeded Ieyasu to avert any possible subversion until the country finally opened up to the West in the middle of the nineteenth century. The feudal lords were required to spend one year in Edo and the next on their lands, during which time their families were invited to stay in their Edo home, officially as guests, but in reality as hostages of the shogun. Each feudal lord had, on average, three residences: one for himself, one for his family, and one for his vast entourage. The city, therefore, was characterized not only by several hundred palatial homes, but also by the presence of tens of thousands of people who needed supplies and services of every kind.

It has been calculated that this system, including travel to and from their land, cost each daimyō between seventy and eighty per cent of their income. The system had several distinct consequences. First of all, it meant that the feudal lords were seriously indebted to moneylenders and merchants from Edo and Osaka and thus prevented from accruing sufficient funds to arm themselves and pose a threat to the Tokugawa. At the same time, it contributed to the growth of the urban classes, especially those involved in trading and financial activities, but also in the crafts. Lastly, it also helped to spread Edo’s habits and mores throughout the country, contributing to the growth not only of a national culture, but also of a sense of national unity.

The most interesting consequence, however, arose from the developing relationship between the military aristocracy and the urban classes, which gave birth to a new, proto-modern society with a popular culture quite similar to the one developing in Europe at the same time. It found its main expression in the Floating World, ukiyo-e.

The term ukiyo is of Buddhist derivation and originally defined the condition of impermanence associated with everyday life and its attachments. But in the seventeenth century, this meaning was turned on its head and the same word came to signify and value the fleeting pleasures of parties, fashion, the theatrical world, mercenary love, clandestine passion, and the ephemeral—in other words, of those very attachments that Buddhist doctrine warned against.

Okumura Masanobu Edo Love in the Three Capitals, c.1710–15

Okumura Masanobu Edo Love in the Three Capitals, c.1710–15

New passions erupted after being repressed for centuries, overthrowing time-honored values and creating a new aesthetic vision. City life and close contact with countless attractions altered lifestyles irreversibly, not only for the various strata of the population, but also for the samurai. The ethical codes of the sword were no more than rhetorical without a battlefield in which to test their efficacy. And the peace imposed by the ruling Tokugawa dynasty had stifled the possibility of any internecine conflict. The principles that were taking hold of the country exalted the values of everyday life and challenged ancient traditions of chivalry where the relationship between lord and vassal had been paramount.

Love and sensual passion, too, which had been tightly contained within a straitjacket of duties and obligations, burst out uncontrollably and overturned values previously seen as given. Money, once despised to the point that a samurai should not have been able to distinguish its different denominations, gradually became the measure of value, synonymous with quality for those who possessed it, regardless of their social class. The rich chōnin, the city man, was able to experience, in the way that best suited his tastes and needs, pleasures and emotions previously reserved for the elite. This new concept of life was primarily transmitted through the theater and its actors, fashionable beauties, works of fiction, excursions to famous places inside and outside the city, and the paintings, prints, and books that illustrated that world in all its aspects.

It was a society where the new tastes and aspirations grew around kabuki theaters and “nightless cities”—pleasure quarters like Yoshiwara, where high ranking courtesans started a trend for showy, opulent dress and invented new canons of gesture and behavior based on entertainment, following the latest fashion, and alluring and spurning at the same time. The pleasure houses, besides being a meeting place for revelers seeking all kinds of enjoyment, turned into veritable salons where one could meet merchants, actors, intellectuals, artists, publishers, and aristocrats attending incognito, free from the rigid formality of their everyday existence.

These “green houses” (another term for pleasure houses, borrowed from the Chinese tradition of Nanking) gravitated around the oiran, the celebrated courtesans of Yoshiwara in Edo, of Gion in Kyoto, and of Shimabara in Osaka. It was there that the etiquette of seduction found expression in a formal canon of the highest degree of perfection and naturalness at the same time. Women who were able to improvise lines of poetry in response to those thrown at them as a challenge, mistresses who had various styles of calligraphy in which to pen a witty reply, who were as proficient in flower arranging as in the secrets of love, capable of supporting or destroying the career of an actor or publisher, these “castle-topplers,” as they were sometimes called, dictated the rules of the latest fashion and manners.

In the art of the Floating World, which better than anything else reflected this new society, erotic images represent a case apart. To a large extent they are pornography pure and simple, titillating voyeuristic images in a city like Edo where between the seventeenth and the nineteenth centuries the male population far exceeded the female one, and where homosexuality and bisexuality were far from rare. This genre was primarily associated with the format, both cheaper and easier to use, of illustrated books, and in recent years research into it has proliferated. Even when the production of these types of works benefited from the input of famous artists and writers, their function was practical rather than aesthetic, as some recent studies have pointed out.

Quite different was the case of paintings and prints (the latter often gathered in albums but also available for sale individually), among which true masterpieces can be found. They were produced in smaller numbers, and in many instances depended on specific commissions, especially in the case of paintings. Albums usually consisted of twelve sheets, the first of which, more chaste than the rest, acted as a face-saving device for the censors who, by tacit agreement, never examined the work past that first image.

Scene from Isoda Koryūsai Prosperous Flowers of the Elegant Twelve Months (Fūryū jūniki no eiga), 1772–3

Scene from Isoda Koryūsai Prosperous Flowers of the Elegant Twelve Months (Fūryū jūniki no eiga), 1772–3

Some of the ukiyo-e artists were extremely fine painters and almost all were superb printmakers, even though in Japan that activity was different from what it was in the West. These artists were responsible only for the pictorial element of the work; the actual carving of the woodblocks and the printing process itself were instead the responsibility of highly specialized teams under the leadership of a publisher. Consequently, the artist was able to design a great number of works without being burdened by the task of materially producing them.

This fact is important when looking at circulation because, given that the print runs of individual works increased year by year, it meant that vast numbers of sheets were available on the market, many more than for European productions. It has been calculated that in the course of his lifetime Hokusai, for example, produced over four thousand works, not including paintings, and over three hundred illustrated books, most of them in several volumes. Each of these works, if successful, could be produced in thousands of copies through various reprints.

That is why every artist needed a publisher, whose role was closer to that of our theater impresario than to that of a Western printer of graphic works. Working closely with the artist, the publisher would approve the work on the basis of a design the artist had put forward. He would then request a drawing of the print, showing the definitive outlines painted with absolute precision on very thin paper. This drawing would then go to the engraver who pasted it face-down, and therefore in reverse, over a block of hard mountain-cherry wood. Most of the back of the paper was later wetted, scraped, and removed so that all that remained on the block were the outlines of the reversed drawing. The block was then carved in order to leave these outlines in relief.

This is how the basic woodblock was produced. Proofs were printed from this first woodblock, and the artist would indicate the colors to be used (by writing down their names) and where on the picture to insert special effects, such as shading rather than flat coloring. The printer would then run as many proofs off the basic woodblock as there were colors to be printed, and on each of these sheets a single color was indicated. At this point the engraver, having pasted each sheet onto a different block, would carve one woodblock per color, leaving in relief only the area to be printed in that particular color.

Lastly came the actual printing, achieved by pressing a sheet over each of the woodblocks prepared for that specific picture and appropriately inked up, starting with black, followed in turn by the other colors required. In order to ensure that all the colors were “in register,” each woodblock was fitted with register guides (kentō) and for each impression the sheet was placed exactly within the guides, to be printed in turn with each color involved in the process. The artists, who always used various pseudonyms, clearly never signed their erotic prints, but would occasionally write their names on a screen or a painting depicted as part of the interior featured in those scenes.

Like all ukiyo-e, art devoted to erotic subjects underwent a stylistic evolution in the course of the three hundred years of life and development of the Floating World—an evolution that reflected the themes and changes in the society of the day. But without a doubt the most artistically significant period was the second half of the eighteenth century, when life in the pleasure districts reached the highest degree of social and aesthetic refinement. In subsequent decades, the leveling down of fashions and manners and their wide popularization meant a deterioration in the quality of life and social relationships, and even the erotic images began to reflect an approach that was coarser and more concerned with quantity than the one that had found expression in the world of the grand courtesans of Kiyonaga, Utamaro, or Eishi.

Towards the end of the Tokugawa shogunate, the bakumatsu, the art of the Floating World and its erotic paintings and prints reflected a profound change in taste. In brief, what can be observed is a trend in which richness and opulence, in both the colors and the depiction of human figures and clothing, replace the elegance and refinement that had characterized the second half of the eighteenth century. The emotions delicately expressed in the faces and gestures turn instead into shows of strength and power, and the erotic scenes increasingly become images of strenuous exercises if not of struggle and violence.

Japan, in the meantime, had changed radically, foreshadowing its transformation into a modern state: the social and political pressures that had forced its newly emergent social strata into forced coexistence had given rise to an artistic and cultural phenomenon of vast dimensions. But from this contradiction there emerged the society and culture of the Floating World, a manifestation of a country fully engaged in the process of modernization, though with its own forms and traditions—a world in which these erotic images played a very important part.