The Harlem Renaissance denotes a specific period of black cultural flourishing, which began in the early 1920s and ended just before World War II. While white historiography often typecasts the movement as a moment of “birth,” black artists were in fact combining European modernism with centuries of formal innovation within African-American and African art. Bolstered by the economic promise of northern industrialization and a long tradition of black cultural organizing, members of the Harlem Renaissance such as Langston Hughes and Zora Neal Hurston were celebrated by a Western avant-garde that had previously been white-only (even as its “pioneers,” such as Pablo Picasso, heedlessly appropriated black culture). The Harlem Renaissance continues to be a formative cultural moment, with incalculable contributions to sculpture, painting, music, and literature. This essay on the Harlem Renaissance is excerpted from Phaidon’s Art in Time.

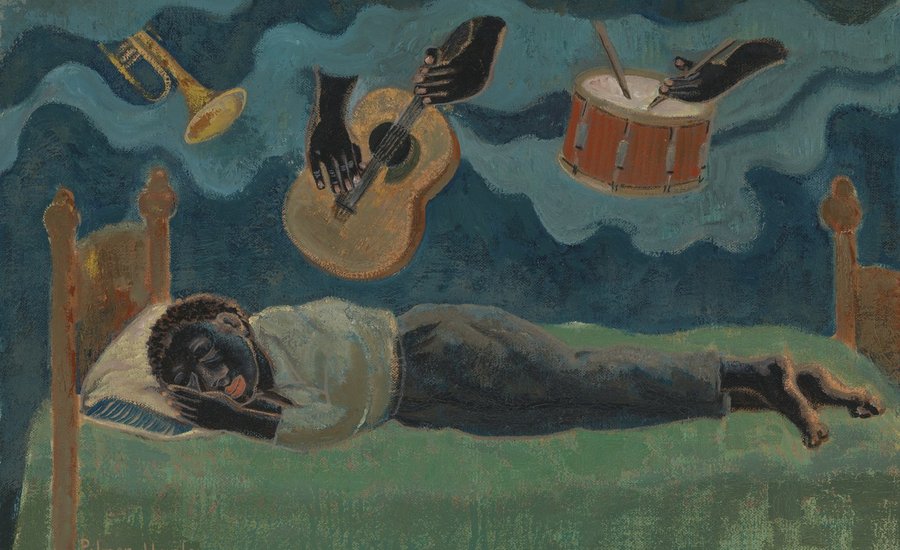

“So far as he is culturally articulate, we shall let the Negro speak for himself,” declared the Harvard-trained philosophy professor Alain Locke in his anthology The New Negro (1925). It was time, he claimed, to make way for an artistic, literary and musical culture created by black artists rather than being about them. A flowering of black creativity centered on Harlem, New York, from the early 1920s to the mid-1930s. Among the best known figures to emerge were jazz musicians like Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong and dancer Josephine Baker, but painting was also a mouthpiece by which African-Americans expressed a racial pride that went beyond prejudiced stereotypes.

Harlem became a cultural center partially as a result of the movement of African-Americans from the rural South to northern cities in 1919-26. While the abolition of slavery in 1865 and the end of the civil war had made changes at an official level, racism was still rife throughout the twentieth century. The end of World War I brought the promise of jobs and a better quality of both physical and intellectual life as a result of northern industrialization. Harlem artists such as Palmer Hayden (1890-1973) expressed their dual identity: in The Janitor Who Paints, the smartly dressed beret-clad painter, surrounded almost comically by the tools of a cleaner, is in part a challenge to the convention that art must be secondary to “real work” for the black man.

Pride was to be found in full participation in American society. Harlem artists wanted to reclaim the stereotypes and caricatures that had been sued against them to redress the power relationship and take control of their depicted identity. In Les Fétiches, Loïs Jones (1905-98) combines masks from five different tribes, overlapping them to suggest vigorous movement; she internalizes the Eurocentric modernist appropriation of African art, turning the notion of Primitivism on its head by approaching the canvas as a black woman. Similarly, William H. Johnson (1901-70) uses broad, imprecise brushstrokes, which had come to signify “primitive” subject matter, fusing this with the conventions of self-portraiture; the presence of a paintbrush in his right hand and his confrontational look make this an assertive image that precludes mockery.

Aspects of Negro Life by Aaron Douglas (1899-1979) was a cycle of four murals commissioned by the Public Works of Art to decorate the section of the New York Public Library intended for research into black culture; it is part of an official attempt to take African heritage seriously. Douglas combines imagery from African-American history with contemporary life, incorporating the influences of African sculpture, jazz music, and geometric abstraction. His celebratory scenes suggest the possibility of reconciling aspects of black identity with contemporary American society.

The notion of a renaissance (rebirth) is problematic in describing the output of Harlem. It expresses the “rebirth” of the black American’s identity through the medium of artistic culture, but it is unavoidably linked with a history of Western European art, suggesting analysis from that angle. Nevertheless, the implication that there had been a rupture in black culture is not universally accepted, and some interpreters feel that it had been continually present but previously ignored.

RELATED ARTICLES:

What Was Photo Secession? Photography's Battle with Painting

What Was Arte Povera? Hair, Horses, Cabbage, and Italian Artists' Response to the War

[related-works-module]