"Bad-boy" brothers Jake and Dinos Chapman have perfected Shock Art with an oeuvre of perverse works that appeal to our notions of taboo and disgust. In 2008, they exhibited the original watercolor drawings of Adolf Hitler (the artists doodled over them using a Hippie aesthetic); in their sculpture Hell (2009), they arranged miniature Nazi figurines into the shape of swastikas; and they've been known to engage in public debacles with journalists and other artists, often criticized for their controversial statements. And yet, their work has been the subject of exhibitions at prominent galleries and institutions like Gagosian Gallery in New York, the White Cube Gallery in London, the Tate Britain in London, the Triumph Gallery in Moscow, and PS1 Contemporary Art Center in New York. In 2003, the artists were nominated for a Turner Prize (they lost to Grayson Perry.)

But perhaps what the Chapman brothers are most known for is their fiberglass sculptures of naked children, fused together and with disfigured, rearranged genitalia. Once such phonographic piece, Zygotic Acceleration, Biogenetic De-Sublimated Libidinal Model (Enlarged x 100)— a 1995 sculpture featured prominently in the "Sensation" exhibition at the Royal Academy that helped define the Young British Artists movement—is the subject of the conversation below, excerpted from Phaidon's Speaking of Art . In this 1999 recorded conversation, William Furlong asks the two artists about desire, abuse, commodification, and pleasure.

This piece, Zygotic Acceleration, Biogenetic De-Sublimated Libidinal Model (Enlarged x 100) , which is the long title, comprises twenty figures of children between the age of eight and twelve, I imagine, with relocated genitalia, and they are joined together in an oval configuration. I felt quite disturbed looking at this piece, and I thought that what I responded to was a tension generated through combinations of opposites—the grotesque and the extremely matter of fact, the surreal and the real, pleasure and revulsion. I know you’ve talked about the thing that’s important being not the object but the discourse that surrounds the object. Can you elaborate?

One of the points about setting up an object that has certain values placed in opposition to each other is that they don’t necessarily neutralize each other, but they set up a kind of physiological oscillation, so the reading of the work never really becomes clear. I think we were interested in the point at which the object could almost make itself absent by an overburdening presence. These are oxymoronic statements. But it was the way in which we could make an object ambiguous but also ambivalent. I mean that in its psychoanalytic sense. When we said we were not necessarily interested in the objectness of the object, it was a way of trying to decide how a work of art functions, how it operates in terms of the spectator, how it operates in terms of the intentions that almost become possessive about an object. And it seems to me the most interesting thing about a work of art is that is dispossesses intentions. So in some sense the object becomes a residue of all of the things it fails to do. We wanted to make that happen in terms of its materiality but also its otherness.

There’s something that the majority of us feel we own, when we look at imagery of young children, but the interventions you’ve made contradict that sense of ownership and familiarity. You’ve created alienation where normally there is bonding.

In some ways it’s an attempt to produce a kind of love object, but in order for that object to be a love object it would have to be a hate object at the same time. In order to be a perfect desiring object it would have to be simultaneously very spiteful to the viewer, because that, in a sense, is how desire is negotiated.

It is also negotiated by a kind of reconciliation between the two tendencies—destruction and construction—that you seem to embody within one object here.

I think masochism and sadism are constitutive of sexuality, so in order to produce an object which is a perfect vehicle for libidinal projection, that object would have to be simultaneously masochistic and sadistic. So I think that’s the experience of viewing the thing, a sense of ambivalence, having to sort out the moral and ethical content of the work, and a collapse of that framework into something amoral, which is laughter. We were not trying to indicate some dignified discourse. We weren’t necessarily making work to promote some theoretical response that would be commensurate with our notions of what we do. But the work becomes a kind of confessionary object, an object almost to incite self-suspicion. The response to the work becomes an index of repression, so the more vehement the reaction, the more that reaction indicates something about the instability of that moral disgust. That moral disgust becomes a kind of physiological pleasure, but a pleasure that can’t call itself by its proper name. Again, the work alienates and dispossesses us. We know a work is finished when it gives us the sense that it has no personal connection to us. In that sense, the reason for us making the work is to challenge the idea that we have some control.

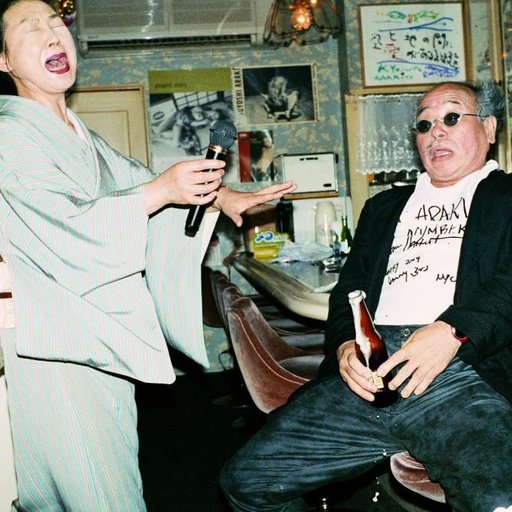

Jake and Dino Chapman. Photo: Rachel King. Courtesy of Blaine Southern.

Jake and Dino Chapman. Photo: Rachel King. Courtesy of Blaine Southern.

You’ve used the term “the commodification of desire.” That presumably could refer to the work here.

I understand desire to be already a relation of power. I suppose there’s a tautology or a contradiction in saying “the commodification of desire,” because in some senses desire doesn’t exist before a commodification. So I think we make a parallel between commodification and iconicity, inasmuch as we’re interested in representation—after all, we’re artists. But we’re trying to think of objects of desire rather than objects that represent desire. Our work obviously has a representative reality. That reality is undermined by its own means.

Is there any narrative that the piece explores?

Instead of narrative it becomes permutation. It becomes a means of exhausting a proposition. I think we’re interested in the idea that each work we make is merely placing things in a different order, which accounts for a different proposition for the spectator. I suppose the work seems to entrap a certain leading element in which a narrative or an ethical content is looked for. It’s interesting that people should raise questions about whether this is an object of abuse or whether this relates to some real dysfunctional situation.

Any figurative sculpture implies some kind of narrative, but it’s not intentional that that should be read in any way. They are just there. Going back to the child abuse thing, that’s a narrative that has to be placed on top of sculpture anyway. I think there’s no narrative other than what the viewer imposes on it.

The way in which we make reference to the body is perhaps how it functions as a dysfunctional set of desiring propositions that are not necessarily at home with each other. So I think the work is already pathologically involved with a definition of what the body is not and is at the same time. So it’s not a question of representation of the body, but it’s a question of understanding how the body can’t possibly represent itself.

In a piece by Julie Burchill in The Sunday Times she writes, “At the end of the century the visual arts are moving irretrievably to the right. What we see in the galleries these days is simply the no-holds-barred, the ultimate representation of right-wing nastiness.” She goes on to talk about child abuse, racism, misogyny, fascism and so on, and she links you with those tendencies. Do you see that as a spurious connection?

The person being called a fascist can’t answer back, because it’s such an ideologically sensitive question. I think we are only representing the conditions of desire in our time. If our work is fascist, it’s because desire is already fascist and involves a certain terrifying of the subject. It’s an ideological question, and a question that would almost require u to redeem our own work, which we’re no interested in doing.

RELATED ARTICLES:

"It Was Maginal": Kenny Scharf on Club 57 and the East Village Art World of the Early '80s

Paul Chan on Erotica, E-Book Censorship, and "Quitting" Art to Become a Book Publisher