Given the centrality of money to human existence, it’s no surprise that it’s been the subject of many classic (and sometimes controversial) works through art history, among them El Greco’s painting Christ Driving the Money Changers from the Temple (1600), Chris Burden’s pecuniary self-portrait detailing his income and expenditure Full Financial Disclosure (1977), and the artists Bill Drummond and Jimmy Cauty (better known as the British dance music duo the KLF) burning £1 million in banknotes on the Scottish island of Jura in 1994.

The ontology of money – the question of what it is – might be roughly divided into two schools. For Aristotle, it was a commodity that fulfilled three functions, serving as a medium of exchange, a unit of account, and a store of value. Set against this theory is the idea that money is a social construct, whose existence depends on “collective intentionality”, which is to say beliefs and attitudes that are shared by a community. Depending on one’s cast of mind, either of these competing theories could be applied equally to the hundred-dollar bill, the Bitcoin, and even the Rai - large doughnut-shaped carved limestone “coins”, found on the Micronesian island of Yap which can measure up to 13 foot in diameter.

In this edition of Group Show, we gather together six works by contemporary artists that are all about the Benjamins, and that employ money both as a motif and a material, as an index of (sometime doubtful) value and as an expression of (all too real) power. Different as they are, what they have in common is a skeptical take on currency, either as a commodity or as a social construct. As that great philosopher The Notorious B.I.G. once put it: “Mo Money Mo Problems”.

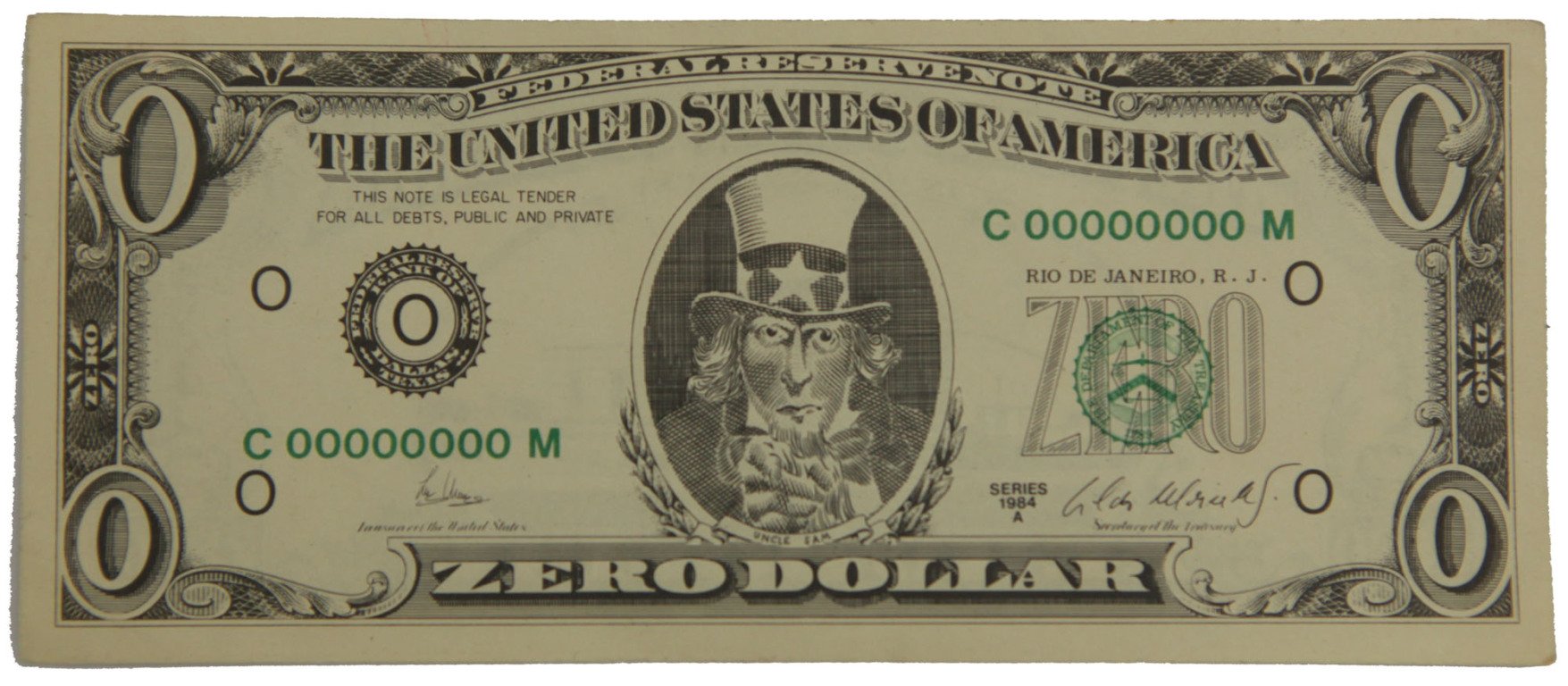

Cildo Meireles, Zero Dollar (1978-1984)

A product of the seminal Brazillian conceptual artist Cildo Meireles’ broader Insertions into Ideological Circuits project, Zero Dollar is – as the work’s title suggests – a facsimile of a US banknote, with a stated value of nada. Aside from this, little distinguishes it from a standard five buck bill. Receiving it in their change, an inattentive person might not notice that the customary image of President Abraham Lincoln has been replaced by the (similarly bearded, although fictional) figure of Uncle Sam, or that the words “Washington D.C.” have been swapped for Meireles’ birthplace, “Rio de Janeiro”. Designed by the artist to be introduced into the money supply, and to circulate from wallet to cash register to bank vault like genuine currency, the Zero Dollar might be thought of as a virus, or perhaps an antibody, which causes us to question our notions of value, and the power relationships on which they rest.

Why did Meireles pick the US dollar for this meditation on money? Perhaps because it is the world’s dominant reserve currency, and one in which oil is almost exclusively priced, bought and sold. Meireles’ banknote not only asks us to consider how we might place a value on nothing (an almost Buddhist question, this), but also foregrounds the dollar’s role in the projection of US might across the globe, not least in the super-power’s South American “back yard”. Possessing no economic potency, the artist’s greenback is reduced to an empty visual symbol, a meaningless promise, closer to a coin from an ancient and long-collapsed Empire than to a real dollar bill.

Virginia Lee Montgomery - Glitch Coin – March 25 (2018)

The United States Mint first placed the words ‘In God we trust’ on a bronze two cent bit in 1864, and today they still appear on 21st century nickels, dimes, and quarters. This is a curious motto to find on the coinage of a country that enshrines the separation of church and state in its constitution, and seems to suggest that the Almighty is the final guarantor of America’s currency. If this were the case, then Virginia Lee Montgomery’s Glitch Coin – March 25 would appear to be a good argument against the existence of an infallible deity. This found object is the result of a rare mechanical failure at the US Mint, which caused a planchet (the blank copper disk that is the precursor to a coin) to be stamped off-centre, creating a misshapen penny, from which Abraham Lincolns’ features seem to slide like toppings from a poorly prepared pizza.

Montgomery’s sculpture, however, also speaks to a second glitch, one that’s not mechanical, but rather institutional. Safeguards are meant to be in place at the Mint to ensure that so-called “error coins” are destroyed, but this one found its way into the artist’s hands, with the help of a subversive employee. Perhaps in the end this is a work about how both coinage and people might escape the order of capital, and in so doing find themselves in new and anomalous shapes.

Sebastião Salgado - Serra Pelada Gold Mine, Brazil (1986)

While the economist John Maynard Keynes famously described the use of gold as money as “a barbarous relic”, there are good reasons why this practice persisted through so much of human history. Sufficiently rare that it’s difficult to overproduce, gold is a relatively stable, non-toxic metal that remains malleable enough to mint into easily portable coins, bars and bricks. Then, of course, there is its yellow lustre, which has a deep attraction to human beings that seems to go beyond mere collectively agreed monetary value, and which is perhaps rooted in its resemblance to the glow of the distant, life-giving sun. For Christopher Columbus – that 15th century herald of Europe’s exploitation and colonization of the Americas – this metal was little short of divine. As he wrote: “Gold is a treasure, and he who possesses it does all he wishes to in this world and succeeds in helping souls into paradise”.

The lauded Brazillian photographer Sebastião Salgado’s shot Serra Pelada Gold Mine, Brazil does not depict an earthly Eden. Rather, this great craggy pit – swarming with toiling, ant-like workers – has every appearance of being a hell. A former economist who first started taking photographs on missions to Africa for the World Bank, Salgado has described his images of this mine as an “archaeology” of labour practices that many viewers might have assumed had long disappeared. Looking at this photograph, we’re reminded of the sheer physical effort it takes to extract gold ore from the ground. At the time Salgado shot Serra Pelada, 50,000 people worked in the mine, making up to 60 trips up and down its vertiginous cliff-face per day, carrying sacks weighing some 30-60 kilograms, for which they were paid a mere 20 cents per trip. We might wonder by what satanic logic was this considered a fair price for their labour, and how much gold would such meagre wages buy.

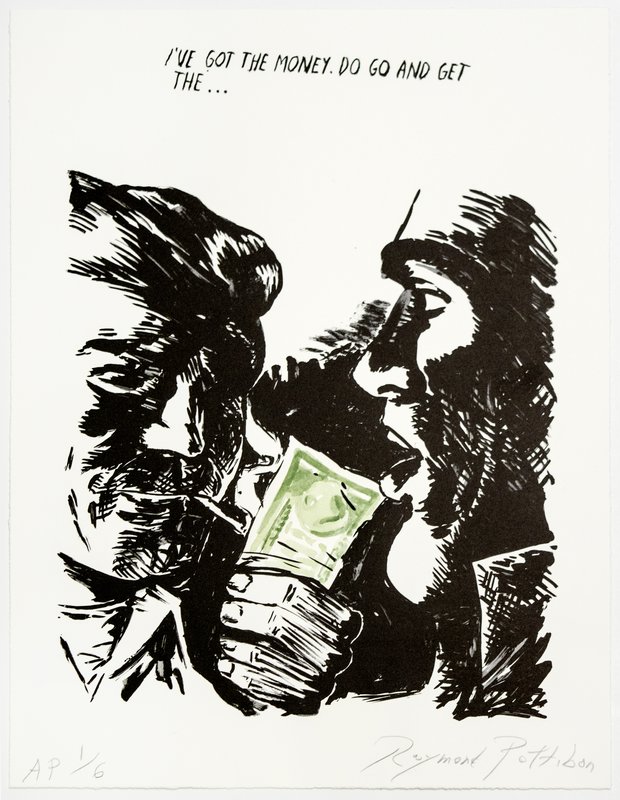

Raymond Pettibon - Untitled (I’ve Got the Money) (2018)

Alongside love and death (two things with which it is often intimately entwined), money is one of the central narrative drivers of great works of fiction – think Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary (1856), or George Elliot’s Middlemarch (1871-2), or Martin Amis’ Money: A Suicide Note (1984). In stories, as in life, the sudden appearance or disappearance of money opens up or forecloses possibilities, pushing characters into new worlds, and towards new understandings of themselves. In his lithograph Untitled (I’ve Got the Money), the acclaimed American artist and LA punk scene icon Raymond Pettibon presents just such a narrative turning point, depicting a cigarette smoking bad boy brandishing a wad of green bills and telling his open-mouthed companion “I’ve got the money. Do go and get the…”.

Ge the what? The gun, the drugs, the girl? Pettibon doesn’t tell us. Neither does he indicate how or where the smoking guy got the cash, or indeed who on Earth these two men are. This is of a piece with Pettibon’s fragmentary, comic book style, perhaps best exemplified by his classic cover art for Sonic Youth’s 1990 album Goo, which features a drawing of a pair of cool kids in sunglasses, accompanied by the words “I stole my sister’s boyfriend. It was all a whirlwind, heat and flash. Within a week we killed my parents and hit the road”. Perhaps the characters in Untitled (I’ve Got the Money) are involved in something similarly nefarious. What’s certain is those greenbacks will pull the trigger on the next chapter in their lives, for good or (this being Pettibon) more likely for ill.

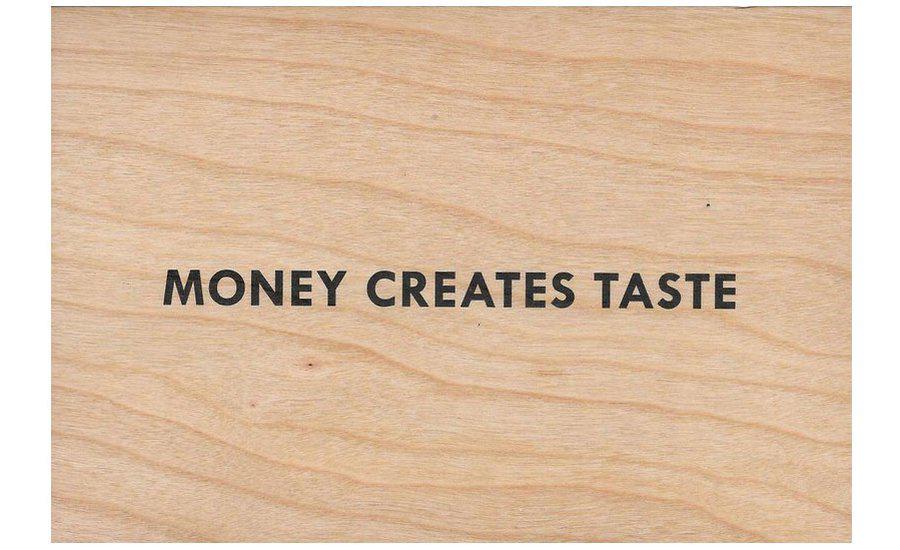

Jenny Holzer - Money Creates Taste (2018)

Jenny Holzer is best known for her text-based works, which employ posters, plaques, light projections and stock-ticker-like LED displays to insert provocative and sometimes disarmingly poetic phrases into public space. These have addressed everything from gun control (“AMERICAN SHOOTING”) to climate emergency (“WE MIGHT SURVIVE”), from the death drive of consumerism (“PROTECT ME FROM WHAT I WANT”) to the toxic social asymmetries that exist in a world dominated by rich white men (“ABUSE OF POWER COMES AS NO SURPRISE”). One of America’s most significant living artists, whose work is instantly recognizable to audiences across the globe, Holzer prizes directness. As she has said: “I used language because I wanted to offer content that people – not necessarily art people – could understand”.

In her screen-print on cherry wood piece Money Creates Taste, Holzer makes a seemingly doubtful claim. After all, if wealth is synonymous with style, what are we to make of, say, President Donald Trump, a man whose vulgar manners, appetite for guzzling great quantities of junk food and predilection for dictator-chic glitz led Vanity Fair to label him (in a telling slur on many aesthetes of modest means) “a poor person’s idea of a rich person”? And yet, the millions of people who aspire to Trump’s lifestyle go a long way towards proving Holzer’s point. Perhaps Money Creates Taste is also a comment on the art market. Do the works that command the highest prices possess the greatest artistic merit, or do they simply reflect the aesthetic preferences – and the values – of the super-rich collectors who pay big bucks to hang them on their walls?

Ryan Gander - Tremendous potential but limited opportunity (2019)

The classic board game Monopoly has a surprising history. Originally titled The Landlord’s Game, it was invented in 1903 by Lizzie Magie – a writer, abolitionist, and feminist activist fiercely opposed to rentier capitalism – and was intended as an educational tool to illustrate the negative impact of concentrating land in private hands. While Magie patented her game, which earned her the princely sum of $500 dollars over her lifetime, this did not prevent the Philadelphia heater salesman Charles Darrow from flipping its economic philosophy, rebadging it as Monopoly, selling it to Parker Brothers in 1935, and in the process becoming the world’s first millionaire games designer. So popular is the game that more Monopoly dollars are printed annually than US dollars, some $30 billion vs. $974 million.

The leading British artist Ryan Gander’s work Tremendous potential but limited opportunity is comprised of a set of eight sterling silver Monopoly counters, which swap out the familiar top hat, sports car, and yacht etc. for objects that speak to the property developer’s trade, among them a a skip full of rubble, a Portaloo, and a pile of three bricks. Decidedly unglamorous, these new counters remind us of the manual labour that’s essential to the business of speculative building construction, something that has prosaic solidity that’s absent from both the fantasies of “luxurious urban living solutions” offered up by developers’ off-plan promotional material, and the buy-to-let landlord’s dream of transforming tenants’ homes into their own personal magic money trees.