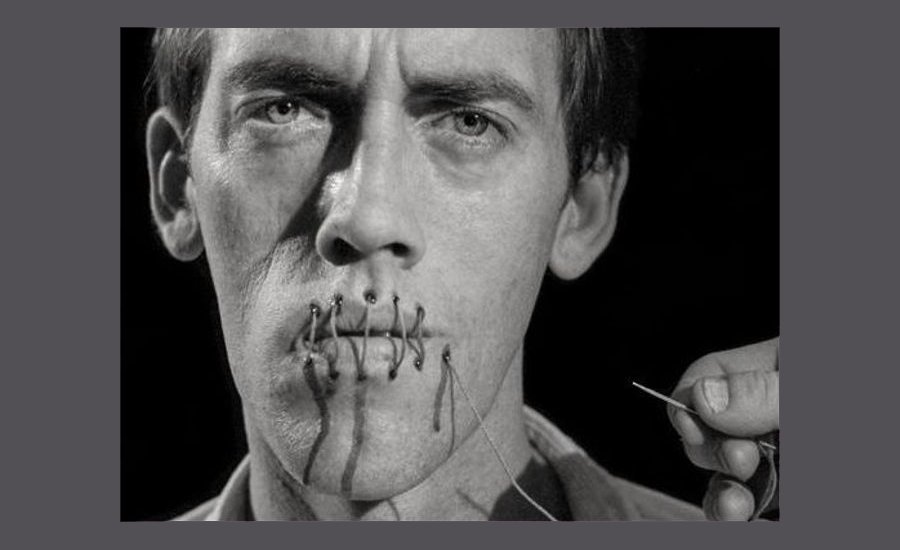

The activist artwork of David Wojnarowicz comes from a place of torment: the artist was abused and abandoned as a child, homeless and prostituting during his youth, and saw his friends and lovers die during the AIDS epidemic before the virus took his own life at the young age of 37. Coming up in the East Village in the early '80s, Wojnarowicz became ensconced in the punk scene, solidifying the anti-establishment sentiments that would later come to define him, moving from poetry, street art, and band posters (he played toy instruments in a group called 3 Teens Kill 4) to large-scale political paintings in the late '80s.

When Wojnarowicz's mentor and lover Peter Hujar died in 1987 of AIDS-related complications, the artist photographed the corpse's head, hands, and feet—and became an outspoken advocate for AIDS awareness. Described by the New York Times as an "irate guardian angel," Wojnarowicz expanded his work to include a wide range of media that, coupled with vehement, anti-establishment rhetoric, sparked significant backlash and censorship from the right wing. Controversy surrounding his work has continued long after his death in 1992: The National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC removed on of his films (that depicted ants crawling on a cross) from exhibition after the Catholic Church protested it—in 2010.

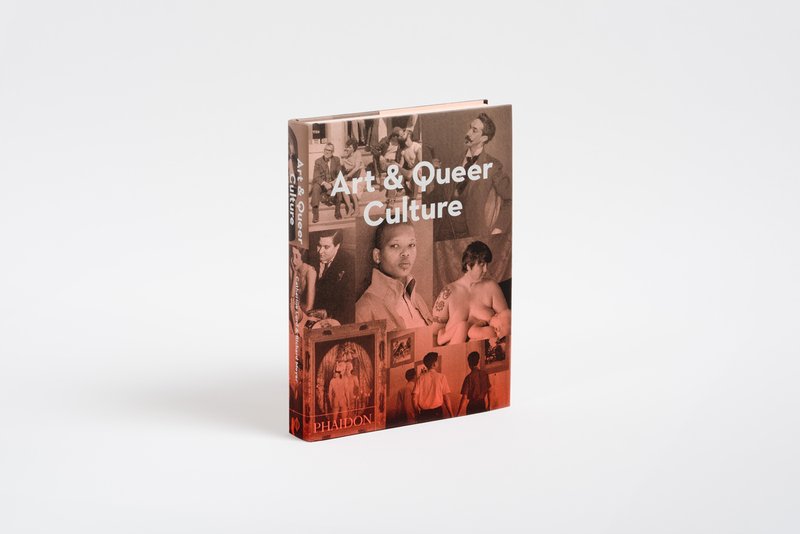

Now, at the Whitney Museum of American Art's "David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night," his work, dealing "directly with the timeless subjects of sex, spirituality, love, and loss," is on view until September 30. Read an impassioned excerpt from his memoir below, taken from Phaidon's Art & Queer Culture .

Art & Queer Culture is available on Artspace for $75

Art & Queer Culture is available on Artspace for $75

[…]

My Friend across the table says, “The other three of my four friends are dead and I’m afraid that I won’t see this friend again.” My eyes settle on a six-inch-tall rubber model of Frankenstein from the Universal Pictures Troup gift shop. TM 1931: his hands are enormous and my head fills up with replaceable body parts; with seeing the guy in the hospital; seeing myself and my friend across the table in line for replaceable body parts; my wandering eyes aren’t staving off the anxiety of his words; behind his words, so I say, “You know… he can still rally back… maybe… I mean people do come back from the edge of death…”

“Well,” he says, “he lost thirty pounds in a few weeks…”

A boxed cassette of someone’s interview with me in which I talk about diagnosis and how it simply underlined what I knew existed anyway. Not just the disease but the sense of death in the American landscape. How when I was out west this summer standing in the mountains of small city in New Mexico I got a sudden and intense feeling of rage looking at those postcard-perfect slopes and clouds. For all I knew I was the only person for miles and all alone and I didn’t trust that fucking mountain’s serenity. I mean it was just bullshit. I couldn’t buy the con of nature’s beauty; all I could see was death. The rest of my life is being unwound and seen through a frame of death. And my anger is more about this culture’s refusal to deal with mortality. My rage is really about the fact that WHEN I WAS TOLD I’D CONTRACTED THIS VIRUS IT DIDN’T TAKE ME LONG TO REALIZE THAT I’D CONTRACTED A DISEASED SOCIETY AS WELL.

On the table is today’s newspaper with a picture of cardinal O’Connor saying he’d like to take part in operation rescue’s blocking of abortion clinics but his lawyers are advising against it. This fat cannibal from that house of walking swastikas up on fifth avenue should lose his church tax-exempt status and pay taxes retroactively for the last couple of centuries. Shut down our clinics and we will shut down your ‘church.’ I believe in the death penalty for people in positions of power who commit crimes against humanity—i.e. fascism. This creep in black shirts has kept safer-sex information off the local television stations and mass transit spaces for the last eight years of the AIDS epidemic thereby helping thousands and thousands to their unnecessary deaths. […]

I scratch my head at the hysteria surrounding the actions of the repulsive senator from zombieland who has been trying to dismantle the NEA for supporting the work of Andres Serrano and Robert Mapplethorpe . Although the anger sparked within the art community is certainly justified and will hopefully grow stronger, the actions by Helms and D’Amato only follow standards that have been formed and implemented by the ‘arts’ community itself. The major museums in New York, not to mention museums around the country, are just as guilty of this kind of selective cultural support and denial. It is a standard practice to make invisible any kind of sexual imaging other than white straight male erotic fantasies. Sex in America long ago slid into a small set of generic symbols; mention the word “sex” and the general public appears to only imagine a couple of heterosexual positions on a bed—there are actuals laws in parts of this country forbidding anything else even between consenting adults. So people have found it necessary to define their sexuality in images., in photographs and drawings and movies in order to not disappear. Collectors have for the most part failed to support work that defines a particular person’s sexuality, except for a few examples such as Mapplethorpe, and thus have perpetuated the invisibility of the myriad possibilities of sexual activity. The collectors’ influence on what the museum shows continues this process secretly with behind-the-scenes manipulations of curators and money. Jesse Helms, at the very least, makes public his attacks on freedom the collectors and museums responsible for censorship make theirs at elegant private parties or from the confines of their self-created closets.

It doesn’t stop at images—in a recent review of a novel in the new york times book review, a reviewer took outrage at the novelist’s descriptions of promiscuity, saying, “In this age of AIDS, the writer should show more restraint…” Not only do we have to contend with bonehead newscasters and conservative members of the medical profession telling us to “just say no” to sexuality itself rather than talk about safer sex possibilities, but we have people from the thought police spilling out from the ranks with admonitions that we shouldn’t think anything other than monogamous or safer sex. I'm beginning to believe that one of the last frontiers left for radical gesture is the imagination. At least in my ungoverned imagination I can fuck somebody without a rubber, or I can, in the privacy of my own skull, douse Helms with a bucket of gasoline and set his putrid ass on fire or throw congressman William Dannemeyer off the empire state building. These fantasies give me distance from my outrage for a few seconds. They give me momentary comfort. Sexuality defined in images give me comfort in a hostile world. They give me strength. I have always loved my anonymity and therein lies a contradiction because I also find comfort in seeing representations of my private experiences in the public environment. They need not be representations of my experiences—they can be the experiences of and by others that merely come close to my own or else disrupt the generic representations that have come to be the norm in various medias outside my door. I find that when I witness diverse representations of ‘Reality’ on a gallery wall or in a book or a movie or in the spoken word or performance, that the larger the range of representations, the more I feel there is room in the environment for my existence, that not the entire environment is hostile.

To make the private into something public is an action that has terrific repercussions in the preinvented world. The government has the job of maintaining the day-today illusion of the ONE-TRIBE NATION. Each public disclosure of a private reality becomes something of a magnet that can attract others with a similar frame of reference; thus each public disclosure of a fragment of private reality serves as a dismantling tool against the illusion of ONE-TRIBE NATION; it lifts the curtains for a brief peek and reveals the probable existence of literally millions of tribes. The term ‘general public’ disintegrates. What happens next is the possibility of an X-ray of civilization, and examination of its foundations. To turn our private grief for the loss of friends, family, lovers and strangers into something public would serve as another powerful dismantling too. It should dispel the notion that this virus has a sexual orientation or a moral code. It would nullify the belief that the government and medical community has done very much to ease the spread or advancement of this disease.

One of the first steps in making the private grief public is the ritual of memorials. I have loved the way memorials take the absence of a human being and make them somehow physical with the use of sound. I have attended a number of memorials in the last five years and at the last one I attended I found myself suddenly experiencing something akin to rage. I realized halfway through the event that I had witnessed a good number of the same people participating in other previous memorials. What made me angry was realizing that the memorial had little reverberation outside the room it was held in. A tv commercial for handiwipes had a higher impact on the society at large. I got up and left because I didn’t think I could control my urge to scream.

There is a tendency for people affected by this epidemic to police each other or prescribe what the most important gestures would be for dealing with this experience of loss. I resent that. At the same time, I worry that friends will slowly become professional pallbearers, waiting for each death, of their lovers, friends and neighbors, and polishing their funeral speeches; perfecting their rituals of death rather than a relatively simple ritual of life such as screaming in the streets. I worry because of the urgency of the situation, because of seeing death coming in from the edges of abstraction where those with the luxury of time have cast it. I imagine what it would be like if friends had a demonstration each time a lover or a friend or a stranger died of AIDS. I imagine what it would be like if, each time a lover, friend, or a stranger died of this disease, their friends, lovers or neighbors would take the dead body and drive with it in a car a hundred miles and hour to Washington D.C. and blast through the gates of the White House and come to a screeching halt before the entrance and dump their lifeless form on the front steps. It would be comforting to see those friends, neighbors, lovers, and strangers mark time and place and history in such a public way.

But, bottom line, this is my own feeling of urgency and need; bottom line, emotionally, even a tiny charcoal scratching done as a gesture to mark a person’s response to this epidemic means whole worlds to me if it is hung in public; bottom line, each and every gesture carries a reverberation that is meaningful in its diversity; bottom line, we have to find our own forms of gesture and communication. You can never depend on the mass media to reflect us or our needs or our states of mind; bottom line, with enough gestures we can deafen the satellites and lift the curtains surround the control room.

[related-works-module]

RELATED ARTICLES:

A Q&A with Anthony Goicolea—The Artist Behind New York's First LGBTQ Monument

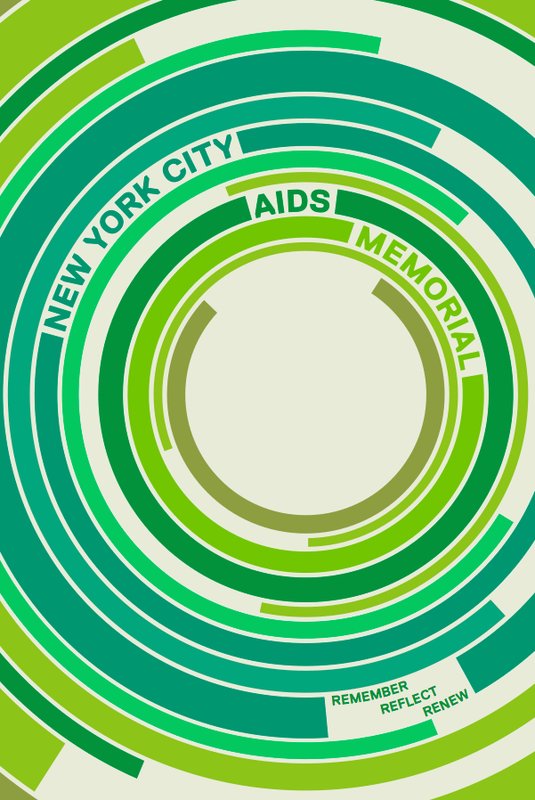

Why Does The New York City AIDS Memorial Matter? Read Testimonials From Leading Cultural Figures