From his 1969 portrait of Bobby Seale in a Superman t-shirt to his new painting of a modern-day London dandy in a fitted pink suit, the artist Barkley L. Hendricks has painted figures that are spatially isolated yet sartorially and attitudinally in touch with vital issues of the day. “His portraits have always been people of the time,” says Elisabeth Sann, a director at Jack Shainman Gallery who has worked closely with the artist.

That’s unmistakable in Hendricks’s latest show at the gallery, which opens on Thursday. It includes two variations on the image, instantly recognizable from national coverage of Trayvon Martin’s death and ongoing protests, of a young black man with upraised arms and a gray hooded sweatshirt drawn around his face. One of them, In the Crosshairs of the States, attaches a confederate flag and American flag bunting to a painted tondo; superimposed on the canvas are the crosshairs and red laser dot of a gun scope. On the subject’s sweatshirt is a haloed black figure with upraised eyes—a nod to Jesus, according to the gallery. Stenciled text around the circumference of the canvas lists states in which members of the police have shot and killed African Americans.

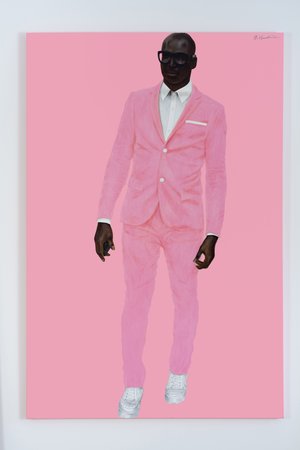

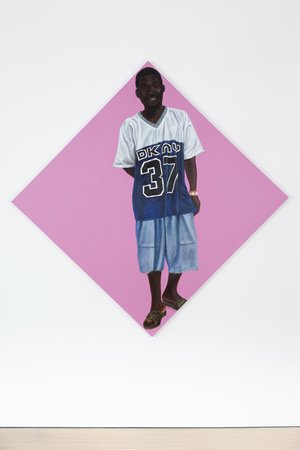

Not everything in the show is so clearly involved with a current national crisis. In addition to the timelessly cool Photo Bloke—the man in cotton-candy pink who became an Instagram sensation when the aptly titled painting was exhibited in Shainman’s booth at the Armory Show earlier this month—there’s a casually attired JohnWayne in a basketball jersey, voluminous denim cut-offs, and diamond earring. And there are two pictures, of a man and woman dancing frenetically in matching white outfits and a woman in a metallic minidress and sculptural platform shoes who is belting out a song with evident strain, in which a complex interplay of color, music, and gesture transcends the date stamps of particular fashion choices.

And as Hendricks is quick to point out, there are experiments in composition and technique in this body of work—including shaped and multi-part paintings and a new focus on acrylics, after decades of working in both acrylic and oil—that also demand scrutiny. In an unexpectedly combative interview in advance of the show’s installation, he spoke to Artspace deputy editor Karen Rosenberg about what critics do or don’t see in his work, whether figurative painting is having a resurgence, and why the word “political” carries so much baggage.

Barkley L. Hendricks, In the Crosshairs of the States, 2016. Oil and acrylic on canvas with bunting and Confederate flag, 35 1/2 inches diameter (painting), 69 x 61 x 6 inches installed. ©Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Barkley L. Hendricks, In the Crosshairs of the States, 2016. Oil and acrylic on canvas with bunting and Confederate flag, 35 1/2 inches diameter (painting), 69 x 61 x 6 inches installed. ©Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

To start off, could we talk about fashion and politics in your portraits and how they intersect? Politics seems to be at the heart of your newest work—

It’s not the heart of the new work. It’s a portion. I’m curious, how much are you aware of my work? Prior to this particular situation?

Quite a bit.

All right, then you’re aware that it’s not basically about the politics. Are you not?

Yes, I’m aware that there are many other aspects of your work. However, the press release for your show at Shainman calls it your “most political to date,” and highlights your painting In the Crosshairs of the States, of a black man in a gray hooded sweatshirt who is holding his hands up and is seen through the crosshairs of a gun scope.

Well, that’s sort of one of those unfortunate situations—a part of promoting my work. It’s a small portion, and certainly a small portion along my career. Now, to address what I’m pretty sure that you have gotten from the press release, yes there are several that are involved with political statements and the way that I put together some pieces deals with my photographing people and with ways of making composites for a particular image that takes me around the world where I’ve traveled.

Some of these portraits are composites, of people that you see on your travels and other things that you come across, as opposed to a portrait of a specific individual?

Correct. It depends on the particular piece. Sometimes they’re direct from photographs, sometimes there are composite sketches, or current events or current images that can be a part of doing my homework.

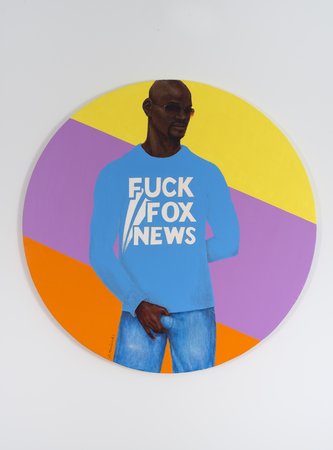

Barkley L. Hendricks, Roscoe, 2016. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 41 1/2 inches diameter. ©Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Barkley L. Hendricks, Roscoe, 2016. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 41 1/2 inches diameter. ©Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Some of those current events are very clearly foregrounded in the new paintings. Why don’t you think of this work as political?

No, I said it wasn’t all political. A portion of it is political. And then we would have to talk about the word “political” in this particular culture, in America. Anything a black person does in terms of the figure is put into a “political” category.

That’s an important point. I’m referring, though, to your use not of the figure per se but of specific images that have come to symbolize the Black Lives Matter movement, such as the man in the hoodie with raised hands.

It’s in direct correlation to what’s happening as we speak.

Yes, exactly. So I guess what I’m saying is, a lot of viewers will see it in a political context. Is that something that’s fair to say?

I mean, it’s obviously meant to reflect what’s going on. And how you deal with the politics of the day, that depends on what your view of America is or is not.

It’s hard to argue with that. Circling back to the topic of style in your work, the gray hoodie is an example of how something that we might initially think of a style choice can become a political statement.

Did you happen to read the piece on the hoodie in last Sunday’s New York Times Magazine? It has a direct relationship to how that particular garment has evolved into a statement that America has distorted with certain people. I mean, I didn’t see anything in that article about Bill Belichick. You know who he is?

I believe he has something to do with football, although that is not my area of expertise.

Yeah. He’s the coach of the New England Patriots. He’s an old white guy. Google him.

Barkley L. Hendricks, Crosshairs Study, 2015. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 4 paintings, each 12 x 12 inches. Overall installation 56 1/2 x 37 inches. ©Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Barkley L. Hendricks, Crosshairs Study, 2015. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 4 paintings, each 12 x 12 inches. Overall installation 56 1/2 x 37 inches. ©Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

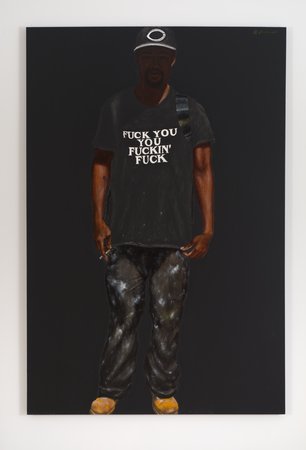

I think another type of garment that is front and center in the new work are these message t-shirts, which are very blunt and confrontational and, in the painting Roscoe, reinforced by an equally strong gesture. Were these shirts something you saw people wearing, or is the text a separate element in the composite?

You’re in New York, I take it.

Yes.

[Laughs] You must be aware of the number of t-shirts with lettering on it, walking around. They’re out there. I came close to doing the “Fuck the Police” t-shirt, but I opted elsewhere.

I’ve been in situations with the police where I’ve been up against a wall: “motherfucker.” The Philadelphia police, are you familiar with them? I’ve had my encounters with them. Luckily it’s not a whole lot, but yes, I’ve been frisked down.

So there’s an element of personal history.

About 30 years ago I did a particular piece that was called F.T.A.—“Fuck the Army.” And I did a series of paintings of a friend at the time when I was at Yale, that was in the Black Panther party. So when I mention people being aware or not aware of certain style directions, I can’t say any more than that.

Barkley L. Hendricks, Manhattan Memo, 2015. Oil and acrylic on linen, 72 x 48 inches. ©Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Coming back to contemporary activism: do you have a view on how art and artists can most productively engage with the Black Lives Matter movement?

To be honest, I don’t really give a shit! I’m doing what I want to do. I paint because I like to paint. I paint because I’m motivated for a variety of reasons that I don’t think are always necessary to blab about. The fact that I’ve had experiences within the context of what’s going on currently adds fuel to particular formats or ideas—that’s a part of what’s going on currently.

There’s obviously a lot more going on in the paintings. But, again, this is an element of the works that, given the context, people are going to be thinking about and discussing.

Don’t write for that! Don’t make the mistake of writing for that. You see, you fall into the same kind of, as I say, trap and stupidity that I’ve been dealing with all my career.

In terms of the press about you?

Yes.

Is there anyone who you think really got it right?

Are you familiar with Rick Powell? Or Trevor Schoonmaker? First of all, they didn’t start off with my being a black artist. It’s a component. It’s a sort of situation that I happen to be a part of, in a nation that’s constantly thinking about black and white. All right? I paint because I like to paint.

With this conversation, we haven’t even talked about the material nature of painting. In fact, we haven’t talked at all about the variety of paint handling that this show has.

Let’s talk about that. What do you mean by the variety of paint handling, and is this a new development in your work?

For a long time, I would be referring to oil and acrylic painting. Well, this particular show, I’m using acrylics more, and doing certain things with acrylic paint that I hadn’t done previously. This particular exhibition gave me a lesson in how to develop my format, outside of the use of oil. This is not abandoning oil, this is making the acrylic more fundamental in certain areas. There’s also the surfaces of certain paintings—wet and dry or reflective against matte imagery.

Let’s move beyond that whole area of “political” that seems to be a part of people’s thinking, rather than introducing them to the methods and style and focus of my work that doesn’t rely on that area of political-ness.

Barkley L. Hendricks, Photo Bloke, 2016. Oil and acrylic on linen, 72 x 48 inches. ©Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Barkley L. Hendricks, Photo Bloke, 2016. Oil and acrylic on linen, 72 x 48 inches. ©Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

I think it will be difficult for viewers, in an intense election year, to approach this new work without getting drawn into the powerful symbolic reference points and statements.

Well, some things are directly involved with what’s going on.

Right.

As I said earlier, ever since I started painting there was a connection to certain areas of the culture that, again, wasn’t a major motivating factor. Just by virtue of what America is or is not. That’s why I like to talk with people who are going to be writing about me, rather than them all of a sudden taking a white myopic approach to what I do. Very little has been said about the fact that I like to paint landscapes.

That’s true. Are there any landscapes in this latest body of work?

No, there are not. But what I’m getting at is that I paint a lot of things. It just so happens that under the circumstance, with this culture, this is what seems to be the major factor. I have no problem with particular work—how can I say—taking center stage, but I paint a lot of different things and it would be great if those who are writing about me start to get hipper to an artist that’s not all political. It’s one of the components. It’s one or two of the images. Let’s not fall into that stupid racial quicksand, which is a part of American culture. Let’s not follow a proscribed line that seems to come to the front rather than dealing with a whole artist.

Now, I can mention a few articles that are totally stupid, by—I was informed you used to write for the New York Times?

That’s right.

Well, I got some stupid articles in the New York Times. There’s been a series of one-track directions that have nothing to do with what my work is. I paint people. I’ve painted white people. That hasn’t been a part of anyone’s observations. That’s not what some esteemed writers have written. You follow me?

I think I do. For younger artists today who are working with some of the same issues of representation, and representation of the black body, do you think they have it easier in terms of the way their work is being received or interpreted? Has there been progress?

That’s a very good question. My wife read something that said that I’m now working with the figure, and had in quotes that representational and figurative paintings will be back. We both laughed—it hadn’t gone anywhere, as far as I was concerned! There is, or was, a leaning towards putting representation and figurative work down, and if there’s a comeback I’m glad to hear.

Barkley L. Hendricks, JohnWayne, 2015. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 68 x 68 inches, 70 1/8 x 70 1/8 x 2 1/8 inches (framed). ©Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Barkley L. Hendricks, JohnWayne, 2015. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 68 x 68 inches, 70 1/8 x 70 1/8 x 2 1/8 inches (framed). ©Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Speaking of portraiture and representation, you’ve made self-portraitstime to time. Is that something you’re still doing?

I haven’t done anything recently. I’ve thought about it. Again, the writing—it shows you what people see. I have a meeting coming up with the Tate Modern. They have one of my paintings there, and someone said, “Is that a self-portrait”? And I said, “How the hell could you think it’s a self-portrait, when the painting is of a nude black man about six feet tall?” I’ve done several nude images, and there were some interesting comments made concerning them.

One of those images was actually a reaction to a critic’s comment—your self-portrait Brilliantly Endowed was a response to Hilton Kramer, who wrote in the Times in 1977 that you were a “brilliantly endowed” painter.

Good old Hilton. [laughs] As I say, there have been interpretations from day one, anytime I’ve gone public. And some of them have been stupid, asinine, and a few other things I’d like to describe. And what can I say? So I’m spending a little time with you, to make some history here. Let’s make some history.

Barkley L. Hendricks, Anthem, 2015. Mixed media including copper leaf, combination leaf, oil and acrylic on canvas, 75 x 77 inches. ©Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.