As the world is enters into a new and uncertain future, global political upheavals will transform the physical landscape, and the landscape of our minds. Below we’ve selected three figurative sculptors from Phaidon’s Vitamin 3D —the must-have index of international sculptors you need to know right now—whose works use familiar forms to play with time, memory, death, and spirituality. Their works serve to remind us of the violent undercurrents in our history, but their ephemeral qualities show us the power we hold and suggest that perhaps the current political climate is but a death rattle of the decaying ancien régime .

BERLINDE DE BRUYCKERE

Born 1964, Ghent, Belgium. Lives and works in Ghent.

In Flanders Fields

, 2000

In Flanders Fields

, 2000

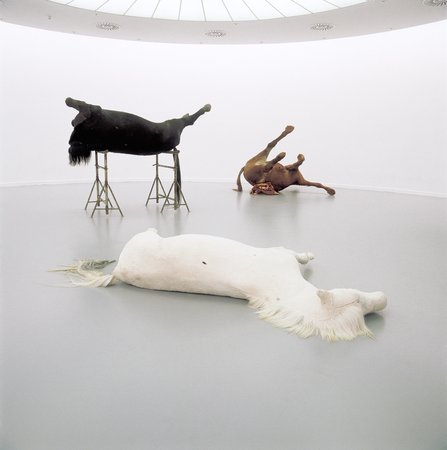

Berlinde De Bruyckere’s is a baroque art, in the sense that it takes creature-suffering as its central theme, giving it a modern parallel in the work of Francis Bacon . She shows us figures that seem to be in pain, crouching or hugging themselves, seeking protection in the warmth of their own bodies. Some are firmly tucked up in blankets; the fabric hugs their bodies, is sewn to emphasize their curves, but also picks out points that reveal missing limbs. Many of the figures are fragmented or, conversely, expanded as a result of proliferations. Horses, sprained and mutilated, are shown directly on the ground or on table-like plinths and showcases. An accumulation of animal bodies presented like this resembles a battlefield, and yet the violent way in which the bodies are bent and fragmented is mitigated by the careful sewing of the hides. Such associations have become concrete references through the titles that the artist gives to her works—for example In Flanders Fields (2000).

De Buyckere also presents figures of almost Biblical stature, reminiscent of martyred figures or the Crucifixion. Their wasted, twisted bodies evoke late medieval Flemish art, which is as important an influence on De Bruyckere (she was born in Ghent and still lives there) as the flesh prevalent in the work of an artist such as Rubens. To depict the human body De Bruyckere works with wax, which she pours into plaster casts made from living models. She captures the liveliness of the skin by mixing pale shades with strong colors that make the surface pulsate. The horse sculptures are also based on casts, in this case using silicone, of cadavers given to her by the anatomy department of the faculty of veterinary medicine at Ghent University. Using a block and tackle set up in her studio yard, she can position the animals’ bodies as she wishes. Some of the horse sculptures hang from scaffolding, attached by one foot only, like slaughtered animals being bled, an image familiar from Rembrandt. But the bodies are shut off, covered with horse hide, a strange skin whose seams show that the hide has clearly been adapted to the mould, emphasizing the sense of protection. Like the fragmented human bodies, the mutilated horses also come together to form a new, complete whole. The visible seams are the characteristic scars of this ambivalent “re-membering,” this way of closing a fragmented body to create an artistic whole.

Into One-Another V To P.P.P.

, 2011

Into One-Another V To P.P.P.

, 2011

De Bruyckere is a modern sculptor in the classic sense. According to one’s viewpoint, the bodies seem almost abstract; figure and space are presented, as in a sculpture by Henry Moore, as a complex pattern of connections. As the drawings she uses to develop new ideas also show, De Bruyckere thinks in categories of volume, weight, and tension. The effect made by the dismembered bodies develops only through the completeness of the sculptural form.

–Beate Söntgen

URS FISCHER

Born 1973 Zurich, Switzerland. Lives and works in New York.

"You" (2007, installation view)

"You" (2007, installation view)

In 2004 Urs Fischer carved gigantic cloud-like holes in the walls of the Kunsthaus Zürich, creating panoramic views that gusted through his exhibition “Kir Royal.” These abrupt changes in architectural scale perfectly suited the shifts in proportion that take place between his sculptures. Looking through one room into another, you could see a cartoony but human-sized skeleton prone on a bench, backgrounded by a colossal captain’s chair, and an even larger packet of cigarettes. The effect was preposterousness on the order of Alice in Wonderland or the out-of-scale comb and soap in René Magritte’s Personal Values . Like Magritte, Fischer stretches and shrivels commonplace objects to exaggerate the consequences once proportions of scale, as well as imagination, go crazy. He undercuts reality but without completely taking it away; when scale is this muddled up, the familiar regresses into an irresolvable dream.

At face value, this slide between reality and fantasy, and the sharp changes in proportional ratios, make Fischer’s work a Surrealist reverb. However, his vehicle for creating these follies is the still-life genre. In 1667 André Félibien, official court historian to Louis XIV of France, set down a hierarchy of genres, codifying art forms by calculating their capacity to interpret life through allegories of moral and intellectual consequence. He ranked scènes de genre— portraits landscapes, and finally still-lives , understood as the inferior reportage of the everyday—beneath the grande genre of history painting . The hierarchy was his enduring legacy, and even today faint traces of his influence echo when pondering art’s impact on an audience. Fischer traffics in the Vanitas still-life—meant to describe the transitory nature of existence. “What I do in my studio—and actually we all do this,” he has said, “is to plow through time […] Every day. That applies to all forms of cultural activity, whether you’re preparing a meal, taking a walk or making a work of art. We’re creating nothing new; we’re just developing what surrounds us.”

"URS FISCHER" (2013, installation view)

"URS FISCHER" (2013, installation view)

The everyday transitory nature of time and the brevity of life recur as themes in Fischer’s work through the symbols of the Vanitas: skulls ( Cockatoo Island Installation , 2007), a candle ( Untitled Candle , 2003), rotting fruit ( Untitled , 2000). His Chair for a Ghost:Thomas (2003) can only invite to mind the ephemeral nature of life. Perhaps his most poignant Vanitas is Bread House (2004), a life-size alpine cabin constructed of wood and loaves of bread, populated by four parakeets too young to fly. As time passes, and the house decays and crumbles, a tart stench rises, evoking death’s closing stages, but all the while sustaining life amongst the birds. Allegories of moral and intellectual significance such as Bread House map time as a process of material transformation and decay while whispering a poetic aide memoire about our own mortality.

– Ronald Jones

[related-works-module]

KRIS MARTIN

Born 1972, Kortrijk, Belgium. Lives and works in Ghent, Belgium.

Watch Kris Martin destroy Vase (2005) on Vimeo.

Many, if not all, of Kris Martin’s works address time, whether it is the historical present of contemporary Europe where he is based or the immaterial time of the soul. Martin has stated that his interest in history and temporality is a natural result of his location: “I enjoy the enormous advantage to live in the centre of Europe,” he has said. “When I look out of the window in my studio in Ghent, located on a little square, I see nothing but history … Jan van Eyck’s studio is fifty meters from mine … I am a product of history.” Thus it is perhaps unsurprising that Martin’s work is more likely to reference work from the Renaissance or Baroque than recent modern production.

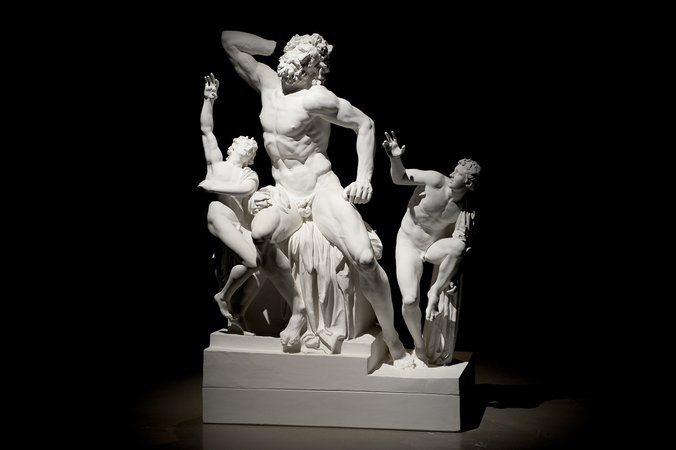

One of his most ambitious works to date, Mandi VIII (2006), is a plaster cast of the famous Hellenist sculpture of the struggle of Laocoön, although the baroquely twisting forms of the serpents whose attack the father and his two sons are desperately fighting off in the original sculpture have been entirely removed. The alarmed expression and physical strain of the three figures suggest a fight to the death with an unknown and unseen tormentor—unnervingly apt for our current condition of alert.

Other works are no less dramatic in their merging of objects, philosophy and attitudes from vastly differing times. Vase (2005), appears, at least to the layperson’s eye, to be a highly valuable Chinese vase. Standing taller than human height, it shows signs of repair following what seems to have been a tragic accident. In fact, Martin deliberately tipped over the vase and pieced together its fragments. The instructions accompanying the work, moreover, dictate that on every new showing (or at every change of hands) it must once again be broken and pieced together. As with the alteration of Laocoön, Martin deliberately plays with our desire for perfection, wholeness, and a corresponding notion of beauty and value. His use of other people’s artworks and artifacts within his own practice suggests at once a reverence for the culture that has preceded him and simultaneously a destructive, even patricidal stance.

Mandi VIII

, 2006

Mandi VIII

, 2006

This mixture of devotion and competition is apparent in a series of works based on texts, and in particular one relating to Martin’s favorite book, Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot . Martin went so far in his appreciation of this novel to copy out the entire book (1,494 pages) in a beautifully hand-transcribed unbound edition titled simply Idiot (2004–05).

Martin has also made works referencing Christianity, such as Trinity (2007), a triptych of watery ink drawings implying a mountainous support for the minute emblems of father, son and holy ghost, and Pieta (2006), a piece of found wood and crystal brought suggestively together to mimic the iconic pose. Asked about his relationship to Christianity, hardly a common topic in contemporary art, Martin has said, “I am a Christian because I am rooted in Christianity […] It is hard for me to understand that people get sick and tired of their spiritual background. For me that is like a fish being sick and tired of water.” His security in his belief allows for the intention of his work to transfer beyond the confines of personal thought. It is, to put it another way, his firmly held faith that allows us to believe as well.

– Jens Hoffmann

[related-works-module]