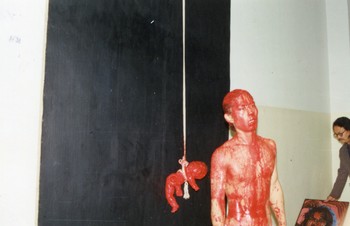

Recognized as one of China's most influential contemporary artists, Zhang Huan has put forth some of the most iconic and visually arresting images of our time with his fearless, breathtaking tests of human endurance and spiritual tranquility. Prior to his arrival in New York City in 1998, Huan had already established himself as a notorious bad boy of the Beijing art scene. His debut performance of Angel at the Beijing National Art Gallery in 1993 found a characteristically stoic Huan covered in a blood-like red liquid, trying to reassemble disembodied doll parts over a sheet of paper. A jarring, visceral commentary on the Chinese government mandate requiring the abortion of any child conceived above the one child per household limit, the show was promptly shut down, and Huan came under China's scrupulous censorship.

Currently on view at The Guggenheim, "Art and China After 1989: Theater of the World" examines the factors that gave birth to such powerful, distinctive Chinese artists such as Zhang Huan. Taking the massacre at Tienanmen Square (in which hundreds of student protesters and civilians were killed by the Chinese government) as a starting point, the exhibition points to the incident as signalling an era in which a decade of relatively open political, intellectual, and artistic explorations had come to a violent end. Counter to that however, was the start of reforms that would launch a new era of accelerated development, international connectedness, and individual possibility (albeit under authoritarian conditions). This confluence of opposing factors generated an almost palpable amount of cultural friction. Rising from this period of flux were artists who were simultaneously criticizing and catalyzing these tumultuous changes, creating works that challenged typical East-versus-West dogmas and Chinese political frays in order to address broader and more nuanced issues of identity, equality, ideology, and control in an increasingly globalized and fluid world.

In the following interview from Huan's 2009 Phaidon monograph with curator, critic, and art historian RoseLee Goldberg, Huan discusses how, in spite of its censorship and oppressive politics, China is still the place the artist pines for and calls home—"Since we've been living in China we look back on those years spent in the West as lost years. China has given me more passion and drive. New York made me sick at heart. China helped me to forget that."

Flowers (2000)

Flowers (2000)

You're really a country boy at heart. You lived your first eight years with your grandmother in the provinces.

Yes, with my grandmother.

And you have talked in the past about how much you feel the countryside shaped you.

I think this is something that will stay with me until the end of my life. And maybe my next life!

It seems to have given you a strong sense of your own physicality, of your body as an expressive instrument. I wonder if you could describe something of that landscape.

Well, I was born in Henan Province in a city called Anyang, and I was sent to the countryside in Tangyin County when I was one year old. The landscape is very flat, and it's right in the middle of China. People from Shanghai call us "the people of the North," but people from the Northeast call us "the people of the South." So we're at a crossroads between north and south. We're given the qualities of being very rough on the edges—they use the word "barbarian" about us—and at the same time they call us delicate. You know, Northern Chinese are described as "yanggang." It means they are forthright, grand, and extroverted. Southerners are "yinrou"—sensitive, exquisite, and introverted. Essentially, Henan combines the masculine North and the feminine South. So I have both qualities. The Yellow River runs through Henan Province, and there are lots of natural lakes and rivers and creeks.

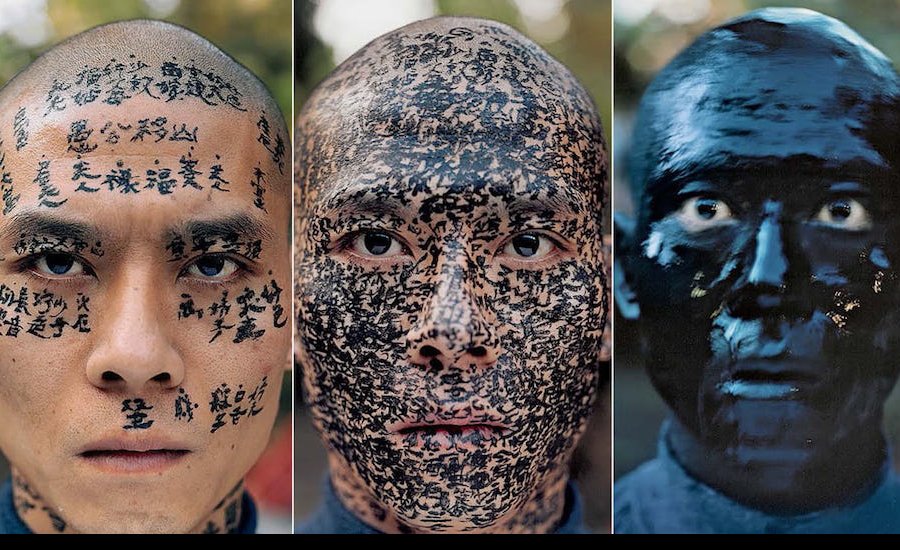

Angel (1993)

Angel (1993)

Your first performance took place in 1993 with Angel in the courtyard of the National Art Museum of China in Beijing. You appeared naked, covered in "blood" (red food coloring) and tore apart a plastic baby doll. Even with fake blood, it was a pretty nasty scene, suggesting abortions of female babies, and the recent massacre at Tienanmen Square in 1989. You were stopped by security and forced to write an apology and "self-criticism" to the National Art Museum. At the same time, it made you instantly visible in the Beijing art scene, and soon after in the international art scene as well. Another performance, 12m2(1994) involved you sitting naked in an outdoor latrine, covered in fish oil and honey, for one hour. In a very short time your body was covered in black flies, making a point about the unsanitary conditions of the public toilets in your neighborhood. The words and images of these performances would reach beyond China's borders, showing the conditions of many artists' lives and indicating a growing art community in Beijing. As with the actions by artists like Marina Abromović in Yugoslavia in the 1970s or Ilya Kabakov in Russia in the 1980s, it's interesting that performance was the vehicle for getting difficult ideas into the world about life under repressive regimes.

Yes, I had discovered that my body could become my language, it was the closest thing to who I was and it allowed me to become known to others. I had been struggling with how to move from the two-dimensional, and then I discovered this new vehicle, my body. It was never for any political or social or cultural commentary. Rather, it was a kind of personal necessity. It allowed me to express some very deep emotions coming from many different places. I was also listening to a great variety of music in those years, including Buddhist or Buddhist-influenced music and Cui Jan, the Chinese father of rock and roll, as well as Kurt Cobain. In fact, music was an essential part of my daily life. I had to listen to different types of music at various times of the day; the Buddhist type of music kept me quiet, kept me calm, and then Cui Jan or Kurt Cobain's music got me going and made me very wild. I think this was an important part of my transition from Henan Province to Beijing, and I really think my development at that time, as a person, as an artist, had a lot to do with music. Music and sex. Sex and music. In a way, it was like the 1960s. Sex played an important role in the transformation of culture and society and of me personally.

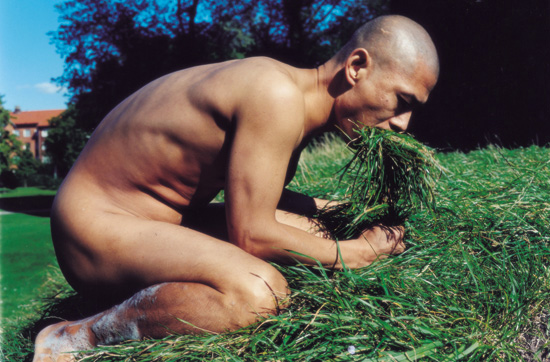

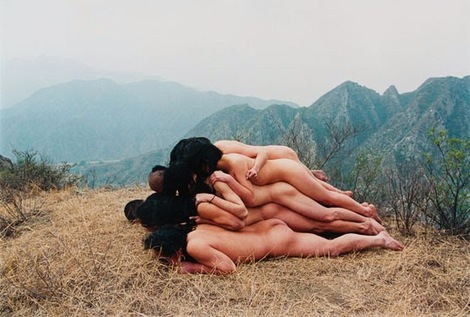

You made several more performances in China, including To Add One Meter to an Anonymous Mountain (1995) and To Raise the Water Level in a Fishpond (1997). Both were highly personalized responses to everyday life, and took on qualities that were entirely your won, having little to do with the material which you'd read about in the Academy's library. They were distinctly Chinese in their subject matter and character.

Yes these works were a necessity for me. The mountain and pond pieces referred back to my need for the countryside. To Add One Meter to an Anonymous Mountain was inspired by an old saying, "Beyond the mountain, there are more mountains," which is about humility. Climb this mountain and you will find an even bigger mountain in front of you. To Raise the Water Level in a Fishpond was an extension of this idea. It's about changing the natural state of things, about the idea of possibilities.

To Add One Meter to an Anonymous Mountain (1995)

To Add One Meter to an Anonymous Mountain (1995)

And then in 1998 you left this all behind and moved to New York with your wife Jun Jun. What inspired your decision to take such a radical leap?

At that time New York was the city of my dreams, so I wanted to go try my luck. I had worked and lived in Beijing for eight years. There was a lot of pressure, and I saw no hope. In 1998 a good opportunity arrived. I received an invitation from Gao Minglu to participate in the "Inside Out: New Chinese Art" exhibition [at the Asia Society].

Your first performances in the United States were a kind of instant reading of American society as experienced by a newcomer from China who barely spoke the language. Pilgrimage—Wind and Water in New York (1998) at P.S.1 appears now to be a highly theatricalized entryway to the West. Set up in the courtyard of this contemporary art centre that was a former public school, you approached a Ming Dynasty-style bed, prostrating yourself in the motions of Tibetan ritual, and lay for around 10 minutes on enormous blocks of ice, surrounded by nine different pure-bred American dogs tethered to the bed. Each part of the performance symbolized the East-West dichotomy that you were obviously very aware of the moment you set foot in the States.

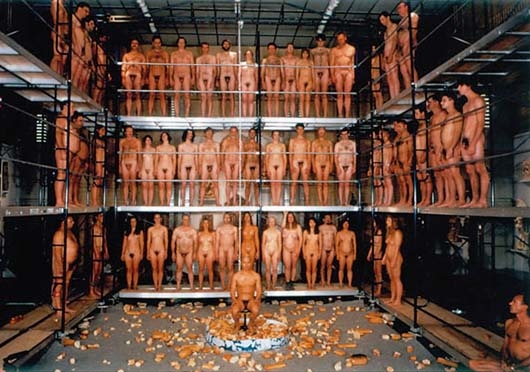

Another work, Hard to Acclimatize (1999), which you presented in Seattle, said it all. It was based on a small Indian sculpture (a 12th century Jain relief from Rajputana) and incorporated a three-tiered scaffold built to resemble three rows of figures in the sculpture. 56 naked Americans of various ages and backgrounds were given instructions, such as "lie face down on the floor" or "behave like animals", while your own ritualized actions contained many references to Tibetan Buddhism, and it ended with 56 performers throwing loaves of bread at you, recalling an earlier incident on the streets of New York when a stranger offered you bread, thinking you might be hungry. It was also titled My America, which further underlines the theme of the "outsider" looking in, if somewhat ironically. Yet you stayed in the States for eight years. Did this feeling of being foreign in New York ever subside? How did your sense of being outside American culture affect your thinking?

That feeling of being an outsider never went away. I am inherently Chinese. This made my feelings and thoughts sharper.

My America (Hard to Acclimatize) (1999)

My America (Hard to Acclimatize) (1999)

You always made stand-alone videos and large photographic documentation of your performances, and in 2000 you started making casts of your own body and including them as "surrogates" or "substitutes" for your live presence. By the time you returned to China at the end of 2005 you had pretty much given up on performance.

In 2005 I did three different performance pieces, and after the last one I realized that I was starting to repeat myself. There weren't good ideas coming out, and also I felt really tired. So I decided to stop cold turkey. But looking back I really do thin that my body was the best way for me to understand different cultures. I am not sure I could have moved around to so many cities and countries and reacted to and absorbed so many different ideas in any other medium. Performance art made it possible for me to do this. It allowed me to keep a strong sense of myself. When I was in New York [from 1998-2005] and still today, I think a lot of people had this concept that everything that we have in China in contemporary art is learned from the West—that we have been led by the horn by the West. For a long time, there was a similar attitude in terms of world power, with China seeming to be a weak country, or at least weaker economically, than the West. For a long time, there was a similar attitude in terms of world power, with China seeming to be a weak country, or at least weaker economically, than the West. So coming from a "weak" country like China I had a sense of myself as a person from a third-world country. It felt that I was coming from the periphery and going to the core. But I wanted to change that dynamic, to subvert it, to treat myself as the core and all the countries that I visited as the periphery. Wherever I went—it could be New York, it could be Rome—I saw the new city as the periphery and my own creative energy as the core, and I combined what I had within me, using my body to connect with the different peripheries. It was a good way for me to be true to myself and not lose myself in another culture. Before I came here [to the United States], a lot of friends told me that I would get lost in the melting pot of New York. "It's such a big city," they said. "You're going to be eaten up by it." So I had to find a strategy to keep my individuality and let it grow out of this idea of the periphery and the core.

Even if you never do a live performance again, it seems to me that your work evolves from a performance core.

I agree. I am sure that the over 10-year experience I've had with performance art has been very important for me. When I lived in New York, people would ask, "Where is your studio?" and I would tell them that I have the smallest studio in the world. It's about 10 by 10 cm, and it's my brain. It's right here. For me, this small, limited space allowed me to think, and it gave me the chance to envision the very big space that I have right now in Shanghai. My experience with performance art was a very important period of my life. It taught me how to conceptualize a work from beginning to end and it allowed me to live through the process of making art. It definitely helped me do what I'm doing now. Living in New York for 10 years also gave me the opportunity to develop my abilities to think individually and critically, and to sharpen my ideas in terms of what's good, what's bad, what's right, what's wrong, and what will work and what will not, in regard to my own work and to others' work as well. My decision-making skills improved a lot, and this is something that I didn't have before I came to New York. I was always aware or having two separate angles, two perspectives. Looking at the States from China and at China from the States and experiencing both places gave me a better picture of reality. Going back to China has given me the opportunity to revisit a lot of things that I took for granted, such as the sight of people in temples lighting incense and praying to Buddha and the old wooden doors of the countryside that you can't see in the city—things that were so familiar yet that seemed foreign from far away. I have a sense of a renewed passion that I had when I was in Beijing, when I was younger—a hunger and a thirst to create art. And that's really all-consuming now.

Pilgrimage—Wind and Water in New York (1998)

Pilgrimage—Wind and Water in New York (1998)

So being away from China allowed you to be more Chinese.

Certainly. The distance provided a clarity.

You bought a house in Queens, New York, where your children were born [in 2000 and 2003], and where they went to school, but in 2005 you returned to Shanghai with the children. You keep a loft in New York City but you are now a full-time resident of Shanghai. What was the trigger that made you return to China?

For me, New York had lost its sense of mystery, and my curiosity was gone. At the same time I wondered if I could get this energy by going back to China. Since we've been living in China we look back on those years spent in the West as lost years. China has given me more passion and drive. New York made me sick at heart. China helped me to forget that.

What music do you listen to now?

I have no time for music now! There's too much going on. I have a very set routine. It's almost like nine to five. I will go to my studio, and then I come back home for my kids.