British minimalist sculptor Rachel Whiteread (b. 1963) is known for her innovative use of negative space as sculptural object. Most renowned for her plaster casts of architectural spaces and utilitarian found objects, Whiteread's haunting, tomb-like works evoke themes of loss, memory, and invisibility.

Whiteread's work is currently on view at Monnaie de Paris as part of the Women House Exhibition, which features the work of 39 artists whose work explores the relationship between gender and space; particularly that of the female to a domestic space. She also has a solo show at the Tate Modern in London, closing on January 21. In honor of the artist's concurrent shows, we've revisited an excerpt from Phaidon's Speaking of Art: Four Decades of Art in Conversation , in which Whiteread spoke with contemporary art critic Michael Archer in 1992 about developing an extensive vocabulary of sculptural mediums, how site-specific works translate into new spaces, and how the installation of a piece can alter its meaning.

---

You've been selected as one of the five British Artists for Documenta 9. Are you making work for that now?

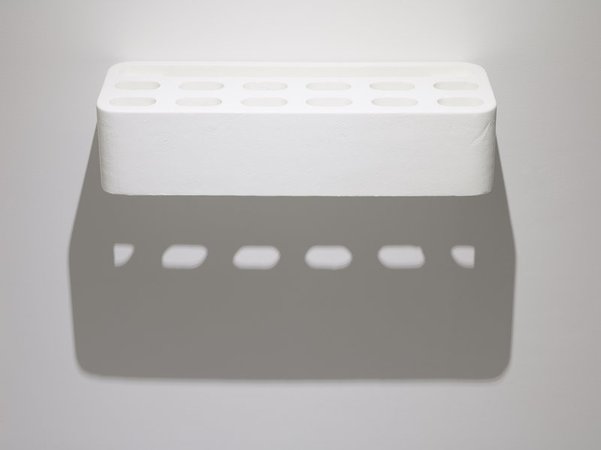

Yes, it's actually in front of us. It's a plaster cast of the space underneath some floorboards. It's probably the most formal thing that I've made. I think it's quite difficult to work out what it is.

It is about a foot thick, and it covers most of the floor area of the studio here. It's about fifteen inches wide. The divides between them, I presume, are the support beams.

The gaps are where the joists were, and there's an imprint of rough wood on the inside. On top, there's this very sensitive colouring that's come off the underside of the floorboards.

Polyshelf, 2009, Available for purchase on Artspace $3,200

Polyshelf, 2009, Available for purchase on Artspace $3,200

Which space did you use to make this cast?

I didn't want to use a particular room. I wanted it to work with the space at Documenta. Once I had all the floorboards and joists in the studio, I was able to make a plan of a fictitious space. I did a lot of drawings and spent a long time trying to work out what the space was going to be like. I could have had an area for bay windows and other things that would have made it far more literal.

And that would have been a repeat of your piece Ghost , which was cast of an entire room.

This piece actually came from the first showing of Ghost at Chisenhale Gallery. When I took it down, there was a kind of map on the floor of where it had been. I wanted to use that idea. I wanted it to be quite sinister, as well—you know, like mass murderers burying bodies under the floorboards or whatever—but by using plaster I avoided being too sinister.

You've used plaster for the past few years, but recently you've begun to work in other materials as well.

I'm going to Berlin at the end of June for a year, and the plan is to start making some work in wax when I'm there. I will probably make another floor using a very yellowy wax, which is like earwax rather than white paraffin wax. After making Ghost , I really wanted to do something flexible. I was fed up with my work being so fragile. I wanted something liberating. I've made about eight pieces with rubber and I think I will continue using it. I want to build up a vocabulary of materials.

Those rubber pieces, the mortuary slabs, were displayed resting up against the wall so that they sank down into the wall and along the floor. There is an awareness of the architecture of the space you're viewing the works in that seems very sculptural.

I trained at a painting school, the Slade, but I never really painted after my first year. I used the floor and the walls. I like to do something that specifically fits in a corner, or something that leans against the wall. The bed pieces that I made in rubber were cast flat, but I knew that they weren't going to stay like that. I was pretty clear about how much they would sag. But it's always a surprise when I take things out of the crate to install them somewhere. I like that change from what you see initially to what you see when it's actually installed.

Installation of Ghost, 1990-2012, Digital C-type Print Available for Purchase on Artspace $676

Installation of Ghost, 1990-2012, Digital C-type Print Available for Purchase on Artspace $676

There seems to be a very strong interest in the relationship of the body to the objects that you use—tables, baths, things like that.

I've always used found objects, things made for simple, everyday usage. For instance, beds are completely international—you find mattresses up against the wall or rotting in alleyways or whatever. And with the first table piece that I made, I wanted to give the space underneath the table some sort of authority. Casting it in plaster monumentalized a space that is ignored.

What exactly do you mean by 'monumentalize'? Are you referring to the traditional idea of sculpture as a sort of memorial?

The first cast-furniture piece I made was Closet, which was the space inside a wardrobe. And when I broke it apart and put it up in the studio, I just felt this enormous sense of release that I'd actually been able to make something that was bigger than I was. I'd been struggling for about six years to do that. It was quite a revelation in some ways.

Yes, it was made in manageable parts.

Ghost was manageable as well, you know. We didn't have to use cranes to put it up. It was just done with ladders and muscles.

That first cast piece, Closet , was covered with black felt.

Yes, I wanted to try and make it a kind of blackness, that space inside a wardrobe that maybe you sat in when you were a kid. In some of my later pieces, I used different oils for separators during casting, which do different things to the surface. The different materials that I used to box the works in became quite important, too. With the bath pieces, I used shuttering—a very rough type of plywood used when digging holes in the road. I liked the idea of this space that you dive into, although I was doing the opposite with it. I'm always very careful with those kinds of details. They're not accidental. I made five pieces using that space beneath the bed, and I used a very coarse hessian in a couple of them so that the plaster would pick up the hair. They have a really unpleasant, uncomfortable surface.

There's quite often a tension in your work between an unpleasantness—either in the quality of the surface or in the feelings that you get from the object—and the warm surface of the material itself.

People have different reactions to the surface of the plaster, but I think it's a very warm material that picks up meticulous detail. There are ten or twelve different plasters on the market, but I basically use two—a superfine casting plaster and a whiter, harder plaster. I have made a couple of pieces in dental plaster, which is a very different material, and it's kind of pink or yellow. But something I've never done myself is color plaster.

House Study, 1992, Image Courtesy of Tate Modern

House Study, 1992, Image Courtesy of Tate Modern

So, to come back to this work for Documenta, you say that the format of the piece was developed in relation to the space where you'll be showing it in Kassel. Does that mean it's a site-specific work?

No, it doesn't. I mean, Ghost was made specifically for Chisenhale, but now it's at the Saatchi Collection and it looks great there.

There are little cut-out areas in opposite corners of the rectangular block, which allow the spectator to be inside the work. This hasn't occurred in any of your other works. There's much more of a relationship between the object and the viewer.

With the bath pieces, you got very involved with the internal element. You came up to these white blocks and looked into them. There were two giant pieces that I made with sinks, where you were like a giant looking down on an archeological landscape. It's something that just crops up every now and again in my work. But with all the pieces, you can look at them quite formally, or you can get completely involved with the surface, or both. I think that's always been in my work.

In one of those bath pieces, you laid a sheet of glass over the top of the bath. Why did you do that?

I made three bath pieces altogether. The first one was called Ether and it had a plughole in it, which I drilled out so that there was a hole going though the work. The second one was called Valley. It had glass on top of it, where I wanted to make a space for a body, so the whole thing was like a sarcophagus. I wanted to trap the space so that it felt claustrophobic. The third one, which also had glass on it, had two holes in the glass and two holes in the plaster, so there was a sense of the work breathing. I wanted it to have some kind of relief. I remember seeing a documentary about the crypt at Christ Church in Spitalfields. They were clearing out lead coffins that were completely sealed. The bodies inside them had deteriorated so much that there was just this lumpy liquid sloshing about inside. And there was a big scare about unleashing the plague and other dreadful diseases. That was something I was thinking about whilst I was making these pieces. I wanted an open one, a sealed one and one that could breathe.

Doorknob, 2001, Available for purchase on Artspace $3,250

Doorknob, 2001, Available for purchase on Artspace $3,250

There was an earlier piece, a cast of two doors put together as one block, which was displayed almost up against the wall.

It goes about a foot away from the wall. You can walk round it, but not many people can fit through that space. Or you have to cock your head to look at it, in quite an awkward way. After that piece was shown here, it was in a show in Berlin called 'Metropolis', and one of the curators insisted that the piece went in the middle of the room so that you had a full view of the doors. And I was saying, 'No, this isn't what the piece is.' And he was saying 'Yes, it is.' And we had a big row, and he told me that he was the conductor and I was a mere musician and I should listen to him.

Do you have any thoughts about the art climate—in London particularly, but also in Britain generally—at the moment?

Someone was asking me the other day if I felt that there was a movement going on in London or England. But no, I can't say I think there is. We're a product of Saatchi's Britain—self-made people working very much on our own. I cant really go into the history of that because it hasn't happened yet. It's something we can only think about in twenty, thirty years' time. In the 1980s there was this big art boom. It meant that a lot of things were possible that hadn't been possible before—or that people of my generation hadn't known about before—which was very liberating. But now there's a very depressed atmosphere, and I actually think that's good. I think a lot of people were making work for the wrong reasons a few years ago. And now it's the real doers that are going to stay, because it's much harder.

[related-works-module]