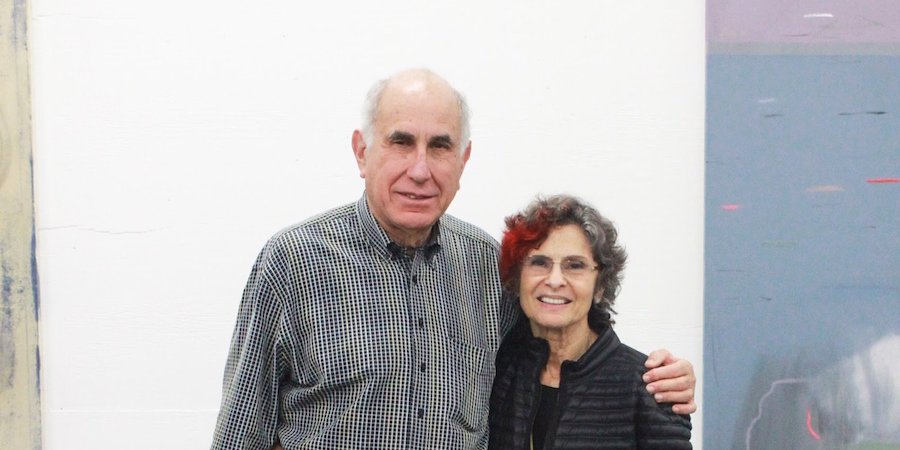

In an art world where trends come and go, artists rise and fall, and buzzy galleries emerge only to quietly vanish, many New York collectors who want to buy fresh, young art with staying power follow a simple rule: find out what Michael and SusanHort are collecting. A couple of rare influence within the early stages of the art market, the Horts have built a reputation not as champions of arena-worthy trophies, the playground of the Pinaults and Broads of the world, but as tireless seekers of intriguing paintings and sculptures by artists who are just hatching into the gallery system, eking out their first couple of shows.

It’s a volatile pursuit with a high likelihood of disappointment—an artist can have a talked-about show and then vanish or go nowhere—but the Horts have an uncanny success rate of finding major talents early on. Among the artists they bought early (if not first) are John Currin, Chris Ofili, Michaël Borremans, and Adrian Ghenie.

The Horts’ influence was unmistakable this January when they held a gala to mark the 20th anniversary of the Rema Hort Mann Foundation, a charitable organization dedicated to supporting both cancer patients and emerging artists that they created in the memory of their daughter, who died of cancer at age 30. To celebrate Rema and pay tribute to the family’s generosity, dozens of artists, dealers, curators, and assorted art-industry heavyweights from across generations crowded into a Tribeca ballroom that was lined with more than a hundred works by people like Michele Abeles, Gina Beavers, Sascha Braunig, Ann Craven, Amy Feldman, Max Frintrop, Jamian Juliano-Vilano, and other young artists that had been donated for the benfit auction. Nearly all of those artists are represented in the Horts’ collection, and many had been given important grants from their foundation—a testament to both their taste and their market-making power.

These days, as a new era of collecting is given rise by the advent of Instagram and the spread of the market, the Horts stand as emblems of old-fashioned patronage. But that doesn’t mean they aren’t paying very close attention to where the market is trending. Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein spoke to Michael Hort about how he and his wife first got into collecting, what’s bothering him about the current gallery model, and what it means to wield enormous influence as a collector.

How did you first begin collecting art?

One piece at a time.

When was this?

1985.

What was the impetus for you to start? Did you ever study art?

No. My wife bought our first piece of contemporary art. She had collected 19th-century American art while our kids were growing up, when we lived in Westchester, a place called Edgemount. She had a nice little collection, a good eye, but I was not involved at all in it—she had a friend that she collected with. The art was on my wall, it was attractive, but it wasn’t of interest to me.

In 1985, we had a mutual friend who was involved with a gallery on 57th Street run by Jack Tilton, so Susan went in and bought a piece of contemporary art. She called me up and she said “When are you getting home tonight?” I said “Why?” She said “I just bought a piece of contemporary art, so the artist is coming over tonight to hang it.” Oh! So I got home and an hour later the artist showed up in Westchester. He walked in carrying this big box, with Jack Tilton in tow, and he walked around the house and hung up his piece. The artwork didn't make a huge impact on me—it was nice, but there wasn’t anything in it I was jumping around about.

Who was the artist?

His name is Paolo Icaro, from Milan. In fact, by coincidence, I believe Artforum wrote a review of him last month. Anyway, he walked in, hung it up, and then we ate dinner. These guys were really fun, Jack and Paolo—they were really interesting, they were really smart, and I really had a great time. Afterward, I went for a walk front of my house, and there was this rock formation I had walked by a thousand times and had never really looked at it beyond thinking “rocks.” They were different shapes, colors, sizes, and after those two left I never walked by that rock formation again without looking at it twice. It became really, really interesting, and I enjoyed it so much. I said to Susan, “I like contemporary art!”

At that time, it was all about the East Village, so we went to the East Village every Saturday to look at art. We got the postcards and brought them back to Jack Tilton to see what he thought, what he liked, and little by little we started collecting. In the beginning, we collected mostly by our ears because we were depending on other people like Jack, and as time went by we finally went out alone.

How long did it take to get your own footing as collectors?

I don’t know about getting my footing, but we were pretty decent collectors within a year, I’d say.

What was your approach like in the beginning?

One of the things that we decided to do was try to collect young and emerging artists. Our plan was that we would buy an artist with the intention to buy more of their work if we liked them. So if we bought a painting and we saw another show, we’d get another painting. Another week we’d collect two more. But we’d nix an artist if they had two or three shows and their prices went way up—we’d never collect them again.

You have to understand, at that time really good art was a few thousand bucks. You could buy Juan Muñoz’s great sculptures for like three or four thousand each, so the next show they might be five or six, it wouldn’t be $30,000 to $50,000. It was only in the 2000s that things really got crazy expensive. This is one of the problems today. If you buy something at $40,000 today, it’ll be $60,000 this time next year.

Who were the artists who really captured your imagination in that late ‘80s scene?

Juan Muñoz, Kiki Smith, Richard Tuttle, many more artists like that. And lots of artists that don’t exist anymore, commercially.

At some point you must have realized that you were buying more art than you could possibly show, especially if you’re buying three or four works by each artist.

Yeah, it was obvious to us at the beginning. We bought a Christopher Wool painting that couldn’t fit in our house, so we had to put it in storage. When you’re a collector, part of it is feeling good about owning it, not necessarily showing it. You can’t show everything, for sure. Early on, we had a Tudor house that was very difficult to show contemporary art in—it had all these angles and things. Other artists we liked early were Marlene Dumas and Franz West.

Did you ever sell works in order to get the funds to buy more?

No, we don’t sell anything.

Really? Not even in the beginning when you were just figuring things out and maybe making some bad decisions?

We have lots in storage.

At this point you must have been meeting and having dinner with these artists. What kind of relationship do you like to cultivate with the artists you collect?

We love artists, and we love to cultivate our relationships with them. But it’s a little bit dangerous if you’re a collector, because if you don’t like their art it becomes difficult.

How do you negotiate that?

You don’t have dinner with them if you don’t like their art.

So you associate with the artists whose work you like, even if they’re unpleasant?

In general.

When did you start going up to buying four or five works per artist?

Right away, not necessarily from one show. We could buy artists one at a time, not three at a time, because the prices weren’t so high and they would go up slowly. The truth is that from 1996 to 1999—so not so long ago—we bought 29 out of 30 shows in a row from David Zwirner. And we paid him $5,000 a month, which is even more incredible. Things were $10,000, $12,000. Jason Rhoades was $5,000, $6,000. It’s crazy, but that’s what the prices were then. I mean, if you buy like that, you get a discount, but still. At that time in the ‘90s, you kind of felt that you could buy any new artist you liked—you didn’t have to decide which one—and also we told ourselves we didn’t have to buy art at the first show.

When did you make the decision not to sell any of the work you bought?

There was no decision about it. We collected what we loved, end of story. To be honest with you, when we first started collecting we never dreamed that anything we collected would be worth $100,000. We just didn’t. $100,000? We better get that out of the house, my kids will spill all over it! In the ‘80s and early ‘90s, that’s what we believed.

We fell into this thing, as far as we were concerned. We had no clue if this art we were buying would have any real value. In the 2000s all of a sudden people with lots of money and no brains decided that contemporary art was a good investment, and today they’ve turned this thing into a joke.

You were really collecting against the grain at this time. Richard Tuttle was a difficult guy to collect, and you were collecting portrait paintings by people like Elizabeth Peyton when that was out of style. What shaped your taste?

But we don’t listen to people, ok? I looked at a gallery just now. I don’t want to mention any names, because they’re nice people, and they send me images of all their artists. It’s a gallery on Madison Avenue and it makes lots of money and has spaces all over the world, and they’re showing shit. It’s beautiful stuff, big stuff, but it’s not real art. It’s decorative, it’s colorful. I don’t need to sit there and look at it and ponder and say “What was the artist thinking?” It’s not an intellectual exercise. Most of art is like that now. Paintings aren’t dead, they never were dead, and if you really think so, well, you can think so.

You bought amazing paintings: Michaël Borremans, Neo Rauch, Marlene Dumas. In fact, the centerpiece of your annual open house that you hold during the Armory Show is always the wall in your bedroom, where there’s a salon-style hang of smaller paintings by the greatest figures of that era.

We bought Borremans and Rauch in Europe before David showed them, but this was the ‘90s, not the ‘80s. The first Rauch we bought was probably in ’96 or ’97. The stuff on the wall is mostly personal, or they’re small portraits. Every year it changes a little bit. There’s a portrait that Marlene Dumas gave us when we went down to visit her. There’s a portrait that Andy Hope did for us, a lot of that kind of stuff. They’re artists we love. The Luc Tuymans was a gift to Susan for one of her birthdays. The Marlene Dumas over the bed was a painting that we bought of a monster eating her family. We bought the first John Currin ever sold, but you know we like John Currin.

You’re obviously very close with some of the artists you collect, but you’re also close to dealers, supporting their programs in a concerted way. Where do dealers fit into your collecting worldview?

I would say the people who had the most influence on us were David Zwirner and Jack Tilton. Jack in the ‘80s to the late ‘90s, and then David from the mid-‘90s on—but, then again, we had a lot of influence on David too. Over time things changed—we did a lot of business with Jack Shainman at one time, we did a lot of business with Anton Kern. Early on, we did a lot of business Jay Gorney until he left town. Paula Cooper as well.

The thing is, the dealers are really important to the artists, I believe. To be a successful artist you have to paint and not worry about making deals, selling art, getting into museums. You have to have a good dealer who’s going to do that for you. It’s a full-time job, being a good painter. We love these artists, we want them to grow, so obviously we have to support the dealers. The good ones, anyway.

But everything’s changing—I’m a little bit cynical about what’s happening. The problem is, most galleries now really depend on lots of sales to make a living. Their expenses are huge. For David Zwirner, his rent was like three grand when we were paying him $5,000 a month. But every dealer has this ambition to have a mall for a gallery now, which means big expenses. At one time, most really good galleries represented about 15 artists. Fifteen artists! That’s who they represented. There was a show every two years for every artist they had, pretty much, and you would go to one or two art fairs a year, because there only were four or five. There was Cologne, there was Basel, there was Chicago, and there was the Armory. That was it!

So you’d go to a couple art fairs with your 15 artists, and that was fine. If you go to 12 or 13 art fairs, you have to have six dealers, because every time you go to an art fair you have to have art. If you need 50 artists, you neglect your artists. And these galleries are neglecting their artists. It’s really a shame. They’re selling the art, but they’re not really dealers. To me, it’s hardest on artists, this race to get bigger and more expensive.

As your stature as collectors has risen, you’ve experienced giant shifts in the way the art market works, particularly in comparison to the scale of the art world in the 1980s.

Dealers at that time didn’t expect to make money. They loved what they were doing, they had to make a living, but that was it. They weren’t going to get rich. If they wanted to get rich they became bankers.

Even so, there has always been fierce competition to get the best work. As entry-level collectors, when you were starting out, did you have to fight to get your hands on the art you wanted?

Yeah, it’s hard. There were things we wanted that we had trouble getting at the beginning, because we were kids. Why should we get the art when there are other people who want it? But there weren’t a lot of collectors, and over time people discovered if you were really good collectors, so it wasn’t very long before we were able to get what we wanted in general.

The other thing is, the big advantage Susan and I have over most collectors is that we have no problem going into a gallery—which we do every year, many times—and seeing an artist and buying four or five works without anyone saying, “This artist is good, they’re ready.” This artist has no resume, they’re having their first show at this young gallery—we have no problem. We believe in our eyes and our knowledge of art, and if we’re wrong, we’re wrong. And we’re wrong plenty, believe me. But if we like it, we like it, and that’s the end of the game. That’s the advantage we have. Most collectors are a little bit timid. They want a little support from someone else who says, “Hey, that's a good artist, check it out.” You get good luck in the end. And now we can get anything we want.

As a collector who’s so invested in supporting these emerging galleries, how does one find the proper balance in terms of ensuring that you support the galleries while also making sure that you’re able to buy the art at the best possible price. Because, obviously, major collectors expect to get discounts.

We get real discounts. I can’t tell you what they are, but we get major discounts. There’s two things that we do: if we buy a young artist, we’re going to show them. You came to our house, you saw four or five people that nobody knows. Some of them you know now, because we bought them a year ago and dealers told everyone we bought it, so all of a sudden some of these artists are known. When we bought Max Frintrop from Cologne, nobody knew who he was. No one. We called some of our friends, and all of a sudden he’s hot. The point is, sure we get good discounts, but we don’t sell them. If we buy five works, we’re not going to sell them. That means something.

In other words, we want to buy the best art we can as inexpensively as we can, and what we give up is that we’re not going to sell your artists. I can’t promise if it goes up to $30 million we won’t sell it, if that happens we might sell one, but until it hits $30 million, no way. And not only are we not going to sell it, we’re going to show it, and you’re going to tell everyone you know that Susan and Michael Hort bought this work, which is going to help this artist immeasurably. Everything we bought at the Armory I later heard about from other people. Before talking to me, you could have walked around and someone would have told you what we bought. And I didn’t tell anybody!

And then when you have open houses to show your acquisitions you have 3,000 people from all over the world come through per day.

Exactly. That gets us what we want, obviously. And it should.

You’re also active on Instagram, posting pictures of the works you buy to @gigihort.

No, I’m not—my wife started all that about a month ago. She has fun with it. I don’t know anything about Instagram. Her friend Carol Server told her about it—great woman, great American, great art collector. She told Susan about Instagram, pushed her on it a little bit, and now she said she likes it. From time to time she’ll promote what she thinks is good.

You spoke earlier about how many galleries have expanded to the level where they have too much overhead and need to bring on too many artists to make ends meet, meaning they can’t properly take care of them. Nowadays, there are a number of new models that are emerging in the market where artists don’t necessarily have to rely on the gallery system. A friend of yours who lives in Los Angeles, Stanley Hollander, runs a place called Hooper Projects that represents one kind of new model. My understanding is they provide a free residency for artists to work out of a studio complex, with the arrangement that Hooper Projects then gets to claim a certain number of the best works that are made during the residency. How does it work?

The artists work there, they make a little money, they build up art, and then they get a gallery. Christian Rosa had a residency there, and lots of people discovered him that way, and now he’s having a show at White Cube. Another artist had a residency there and he’s now about to show at James Fuentes. They’re getting exposed, but part of it is what I just told you. The artists are not really satisfied that galleries are galleries. They need dealers. The really good galleries nowadays are scrambling to make money, getting bigger and getting more branches, and showing at 12 or 15 art fairs, therefore they’re representing more artists than they can really take care of. If you have 50 artists and a curator comes in to talk to you, which one are you going to talk about? You can’t talk about all 50, so artists are kind of resistant to that. It’s a big problem. I had a bunch of artists at my house in New Jersey this summer, working. One of them was kind of happy with his gallery. All the rest of them were not.

What do you think is the solution? Is this a place where collectors should step in?

They are stepping in. I’m not stepping in—I have no interest in representing anything. But I understand how these things are coming about now. I don’t know where it’s going, though. One of the things is, as long as art keeps going up in price so quickly, as it is now, it will attract a lot of people to it for all the wrong reasons. Once it levels off or drops to a realistic level, which I’m sure it will at some point, then we’ll really see what’s going on.

Stay tuned for the second half of our interview with Michael Hort, in which he says where he believes the gallery system is going, and which artists he’s collecting today.