The lasting influence of Bruce Nauman , an artist widely celebrated for his video, performative, and neon sculptural works, is easily traced when looking at contemporary art today. Working with themes of death, violence, spirituality and sexuality; often explored through the use of text; Nauman's works are nearly impossible to seperate from the political events at the time they were made. However, throughout his career, Nauman was against the notion of art as a direct political statement. In 1980, he famously declared "I don't think I know any good art, (or) very very little good art has any direct political or social impact on culture."

In anticipation of MoMA PS1's forthcoming exhibition "Disappearing Acts," opening in October 2018, we revisited this excerpt from Phaidon’s 2014 Bruce Nauman: The True Artist , in which art historian and critic Peter Plagens writes of the artist's aversion to making overtly political art.

---

"Mixing art with politics," a wag once said, "is like mixing gin with snot: it ruins the former and fails to improve the latter." Though simplistic, the dictum possesses at least a bit of truth. If the chief aim of a work of art is to change or reinforce a good many people's opinions on a political issue, then it usually has to sacrifice one or more of the traditional aspects of what we call, in the modern or comtemporary sense, a work of art. If it's too well crafted or made from too precious a combination of materials, then the audience wonders if the artist––acting as a political messenger––is being irrelevantly indulgent, or is bogging down the original message in unnecessary material distractions. If it's too beautiful, the audience might veer off into an aesthetic reverie instead of being compelled, as they say in politics, to stay on-message. And if it's too ambiguous––ambiguous being one of the hallmarks of much of modern art––then the audience simply might not get the political message.

Most serious modern or contemporary art that has a political message is politically effective only in the way that a street protest is effective: it testifies that this artist is one among many sensitive, talented and intellegent people who come down on a given side of a political issue. If the artist is well-known and generally respected, his or her work of "political art" functions additionally like a signature of a famous person on a petition. One of Nauman's contemporaries as a graduate at U.C. Davis, the artist Stephen Kaltenbach, put it this way: "Making really good political art is impossible. If you hope to deliver a point, it has to be blatant, and that takes it to being a lecture."

On the other hand, some people have contended––and still contend––that there's radioactive political content in a great many seemingly non-political content in a great many seemingly non-political works of art. "Do you agree with [the poet W.S.] Merwin," asked the narrator at the end of a 2009 episode of the PBS television program Bill Moyer's Journal , "that political art is 'almost always propaganda,' or with folk-musicoligist Irwin Silber that any artist who 'tries to deal honestly with reality in this world' is bound to be political?" Yet another view is that the real political feat of modern art was to have been political enough in the first four decades of the twentieth century to have broken in the first four decades of the twentieth century to have broken in the first four decades of the twentieth century to have broken free from the unstated but implicit obligation to be political in the service of the state. "Someday," the great formalist art critic Clement Greenberg said, "it will have to be told how 'anti-Stalinism,' which started out more or less as 'Troskyism,' turned into 'art for art's sake,' and thereby cleared the way, heroically, for what was to come"––meaning Abstract Expressionism , in America and abroad.

Like all American artists of his generation, Nauman spent his formative years surrounded by the political clashes over the war in Vietnam, the Civil Rights Movement (particularly the race riots in American cities) and what was back then called the Women's Movement. But Nauman––at least in his art––stayed apolitical, as did, somewhat to its later chagrin, most of the contemporary art world. Color Field painting and Minimalist sculpture, for example, looked decidedly apolitical, unless you subscribed to the leftist notion that big abstract painting constituted "bank lobby abstraction" and de facto support of high-finance capitalism, and that Minimalist sculpture was, owing to its militant lack of beaux-arts refinements and doodads, a kind of proletarian, homage-to-factory-workers brand of art. But both styles evidenced a rather cool aloofness from the grit of street-level political struggles.

Installation, video, and performance art, while being somewhat less aloof, still concentrated more on expanding the boundaries of art––for art's sake or just for the hell of it––than on delivering a political message or having a political effect. In Europe, those artists whose work was most morphologically similar to Nauman's such as Joseph Beuys and Marcel Broodthaers, were much more political than Nauman. (Beuys even helped to found political organizations: the German Student Party, the Organization for Direct Democracy Through Referendum, the Free International University for Creativity and Interdisciplinary Research, and the German Green Party.)

The Women's Movement was the great exception to the predominantly apolitical art of the 1960s. In fact, the art world was the venue of one of its most emphatic efforts, and the West Coast––with Judy Chicago's " Feminist Art Program," beginning in 1970 at Fresno State College, not all that far from U.C. Davis, and at the Women's Building in downtown Los Angeles opening in 1973––was arguably its most prominent location. But the Women's Movement had a built-in political role for almost any serious work of art made and/or exhibited by a woman. The increase in serious, ambitious artists added more proof that art made by women was as good as any made by men. (Some women artists maintained that, because of its comparative "outsider" nature, art made by women was inherently better than that made by men.) Most artists in the Women's Movement simply wanted a bigger slice of the pie. Whatever kind of art women were making, they wanted the benefits of more exhibitions, sales, inclusion in important museum exhibitions and catalogues, and more thorough and respectful treatment by the art-critical establishment which was still male-dominated.

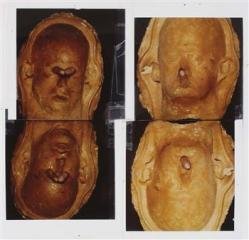

A substantial minority, however, believed in a women's aesthetic (centralized compositions, according to one school of thought, which echoed a utero-umbilical life force, proudly showcasing horror vacui in opposition to contemporary male artist's tendency to cantilever a phallic beam out into empty space). The minority thought this was as essential to the Movement, if not more so, than simply grabbing a bigger share of the goodies in a male-styled art world. In both factions––between which the boundary was often blurred––the "political" content of the work of art was substantially within the creation of the work of art itself, rather than something outside of the work of art, to which it only referred.

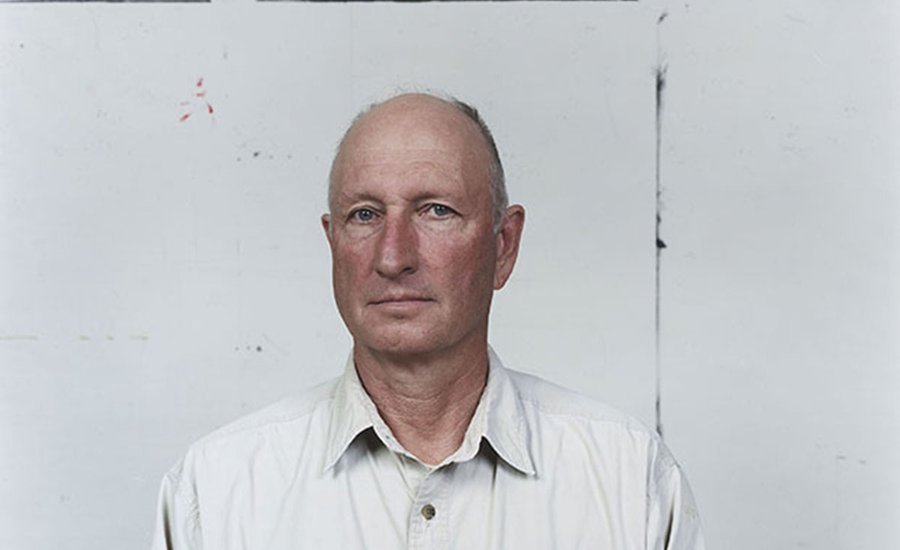

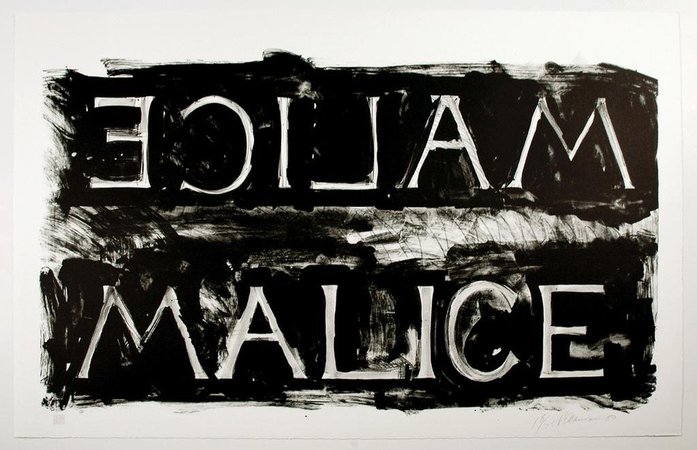

Malice, 1980, Available for purchase on Artspace $10,000

Malice, 1980, Available for purchase on Artspace $10,000

While not totally out of the political loop, Nauman says that in the 1960s and 1970s he was "barely aware of the Vietnam War, because I was too focused on wanting to be an artist." He was quite aware, however, of Ed Kienholz, the greatest Los Angeles modern artist and the prescient assemblagist with whom Nauman traded works early in his career. Kienholz's most important pieces––including the sculpture The Illegal Operation (1962), and the installations Roxy's (1962), The Wait (1964), and The Portable War Memorial (1968)––are "political" in powerful, but non-captioned ways, and the thrust of his whole oevre is towards a searing, bellowing, anguished social criticism. Nauman shares with Kienholz a whatever-it-takes attitude towards materials and physical methods (although Nauman's art is much more morphologically discontinuous than Kienholz's), and a critical regard (as well as a much more inquisitive, philosophical one) of American society as a whole. But where Kienholz worked with cast-off, readymade materials (he believed the finest sociological database in America was the junk store), Nauman almost always bakes from scratch, so to speak. In Marshall McLuhan's terminology of media, Kienholz is "hot" while Nauman is "cool."

In 1980, Nauman declared, "I don't think I know any good art, (or) very very little good art has any direct political or social impact on culture." His work entitled Raw War might reasonably be construed as saying something about the war in Vietnam (i.e., that it was "raw," as in uncivilized). A 1968 drawing and subsequently, a 1970 neon piece and 1971 print, the choice of words is apt––three letters, two powerful short words that are loosely connected (war is raw), relevant to the times, and a perfect palindrome. The drawing is simple and blunt: WAR drawn with no fads or fancy stuff three times in numbered horizontal rows; on the top row, the "R" is the single letter colored in (two red, one primary, the other dark, like dried blood), in the middle one it's the "A," and on the bottom the whole word is in reds. "WAR," the drawing says on the bottom; "RAW," the drawing says in a backward-shash diagonal. The neon version of two years later consists of the word "WAR," "R," "A" (while the "R" goes quickly off), and then "WAR" again. It's about as unvarnished and effective a brief meditation on war as you'll ever see: the blinking neon looks like a little battle on the wall. In its final interarion as a print in 1971, Nauman gives "RAW" front and center position in an aerial view of a three-word, three-row arrangement of the words; it's bright red on a solid black ground. Behind it, in yellow, resides "WAR." Most distant is "RAW" again, in weak white. The alternating of the two words is only implied in this, the most visually complex of the three works. Like many of his works in pared-down language, each of the three versions of Raw War grows on you. The words tumble around in your mind, but never lose their original meaning, or force. The neon piece is, as John Yau aptly puts it, "haunted by itself."

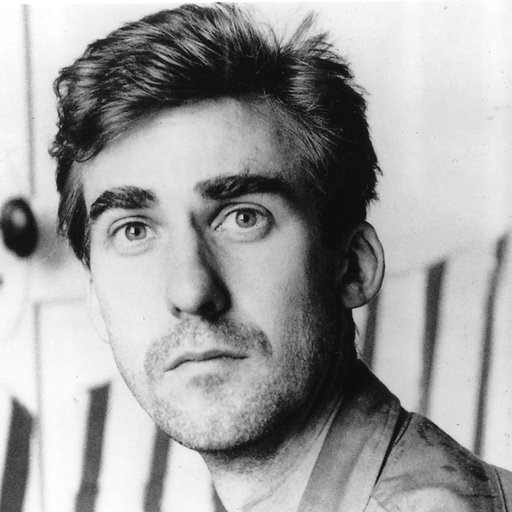

The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths (Window or Wall Sign), 1967, Artist’s proof, neon tubing with clear glass tubing suspension frame, 149.9 × 139.7 × 5.1 cm (59 × 55 × 2 in), Philadelphia Museum of Art

The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths (Window or Wall Sign), 1967, Artist’s proof, neon tubing with clear glass tubing suspension frame, 149.9 × 139.7 × 5.1 cm (59 × 55 × 2 in), Philadelphia Museum of Art

The earlier and more famous neon, The True Artist... (1967) might be construed to contain a hint of commentary about the revealing of mystic truths on the part of artists as amounting to nothing but a bit of fiddling while the world burns. Still, to find any specific and overt political content in Nauman's work up to the mid-1970s requires the viewer to do a considerable amount of reading in. But with Double Steel Cage Piece (1974), Nauman's artistic compass needle wiggles toward outright political commentary.

Produced in the wake of an artist's block of several months' duration that followed Nauman's precocious retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1972-3, Cage Piece is an interior cage constructed of steel beams and heavy-duty metal screening that is quite close to chain-link fencing, and a door to each cage made of the same materials. You can enter the outer cage, the door of which is usually left open in exhibition circumstances, but not the locked inner one. Between the two cages is barely enough room for a person to stand, let alone move, and moving around the perimeter of the interior cage means for all but a super-thin person that the screening behind you rubs your posterior. The feeling is, to say the least, uncomfortable. As critic Ben Davis said about its retrospective appearance at the 2009 Venice Biennale, "A work like Double Steel Cage Piece (1974)...is obviously meant to influect a sense of frustration and panic on its audience."

But what does Double Steel Cage Piece mean? Like a good deal of Nauman's work, it communicates what Lewinian psychotherapists, especially in the 1970s, referred to as "approach-avoidance" or, simply put, mixed signals. You can see all the way through space, but you can't get all the way into it; you can get halfway into the space (meaning inside one of the cages), but once you're there, it becomes more frustratingly apparent that not only can you not get into the interior cage, but that you cannot take a single step forwards towards that goal. Nauman offers something, then holds it back. He does this with "mystic truths"(he tells you they exist and that the "true artist" reveals them, but he won't tell you what even one of them is). He does this with words, offering you "violins" and "sugar" and then brutally deconstructing them with semi-anagram and half-palindromes so that the longed-for sweetness for melody or taste is delivered to neither your ears nor your tongue.

Even with the title of Double Steel Cage Piece , which is a mere description of the conglomerate object, Nauman denies the promise of some meaningful specificity. Yes, you say, it's obviously a double cage, in steel, but what (or whom) is it a cage for, and why? Nauman has never been coyly enigmatic about discussing his work, but he doesn't want to make it any easier for the viewer (either in 1974 or 2009) than he did for his thesis committee of professors at U.C. Davis in 1966. Yet Cage Piece clearly has a political implication. It looks as if it's meant to imprison someone––not after the niceties of "due process" have been observed, but in an ad hoc, makeshift way, after a capricious or corrupt verdict by a kangaroo court. The piece simmers with sinister political potential and, in that regard, brings to mind Picasso's alleged remark to Gertrude Stein after she complained to him that his famous 1906 portrait didn't look like her. "Don't worry, Gertrude," he is supposed to have said, "it will." Similarly, Cage Piece inevitably became political. It was shown in Nauman's Tate Liverpool exhibition, "Make Me Think Me," in 2006 and at the Venice Biennale in 2009. In both instances, what America was doing with alleged Islamicist-terrorist prisoners was an ongoing front-burner political issue.

In 1974, Nauman was as aware of the resonances of a cage as he had been of those who communicated by a narrow corridor five years earlier. But was this also the case with the ordinary rigid, old-fashioned office chair that he used in South America Triangle (1981)? This bare-bones seating item can connote Kafkaesque and Beckettian end games or, worse, a third degree from the police. So it's hardly surprising that Nauman––after having read Cell Without a Number, Prisoner Without a Name , the Argentinian journalist Jacobo Timmerman's memoir of his imprisonment and torture in his country's "dirt war" against its own populace in the 1970s, and V.S. Naipaul's treatment of the same general subject in The Return of Eva Peron and the Killings in Trinidad ––might have found a deadly political metaphor in such a chair. It was to such a universal, punitive chair that Timmerman was tied up and subsequently beaten and subjected to electric shock. Nauman says:

"Up until [that time I read those books], I hadn't intended any work as overtly political. Maybe it took that long for me to be confident enough to step back. One day I made a full-scale wood mock-up and hung it. I hadn't been able to work for many months, and I wasn't sure if I could deal with this. I was finally able to fabricate the steel and make a number of drawings around around the work that let me see it more clearly and accept it."

South America Triangle (1981), Nauman's most Kienholzian work, is a simple piece: a steel chair hanging upside down in the center of a triangle delineated by three steel I-beams about 10 feet long, also suspended from the ceiling by cable. It's usually installed so that the triangle hovers above the gallery floor just above shoulder-level of the average person. In its original conception, the work was to have floated perilously at eye level, with the triangle motorized and rotating, and the chair crashing into it. The visual, kinesthetic impact, not to mention the power of the allusion to torture, would have been much greater, but so would the danger to the viewer's eyes. Nauman also made a very similar companion piece in the same year, Diamond Africa with Chair Tuned, D.E.A.D. which consists of identical components, save that the I-beams in Diamond Africa are four and form a diamond, and the chair, still upside down, is hung at a diagonal.

As political-comment sculpture these two works operate in the same way: the beams form a metaphorical prison and the upside-down chair, from which its implied occupant has either been dropped or to which he (or she) is bound, connotes a person being tortured. The symbolism is direct to the point of being crude and obvious––or at least it seems so in a description such as this one. In person, as it were, the sculptures pulsate with both accusation and empathy. Critic Tyler Green writes:

"The two pieces are masterpieces of suggestion, raised eyebrows in steel and cast-iron. On one hand, there is nothing overt in either of them. On the other, what else could they be about, but the misuse of a human, the institutionalized infliction of terror. Both sculptures reminded me of American behaviors that I'd read about in the 2007 International Committee of the Red Cross report that concluded that the Bush administration tortured detainees. They reminded me of American-made horrors that fill every chapter of Jane Mayer's chronicle of the Bush administration's extra-legal detention and torture, The Dark Side ."

If there's a medium seemingly made for political art, it's neon. Not only is it the nocturnal language of our turn-of-this-century era, but its synonymous––indeed near-identical––with sending an imperative message: buy, eat, see, drink, sleep, save. All that had to be done was to make it legitimate as a fine-art medium, something that was accomplished by Rauschenberg, Johns, Rosenquist, Chryssa and Nauman himself in the 1960s. But just as a standard office chair's ambiguity made it perfect for Nauman's contrariness to turn into a work of art ( South American Triangle ) about a very particular political event (the torture of Jacobo Timmerman), neon's penchant for command specificity (for example, park here) also made it ripe for Nauman's characteristic ambiguity.

Although the younger artist Jenny Holzer works not in neon but in electronic LED signs whose works "move" smoothly (it's an illusion) rather than toggle on and off, her work is probably the closest to Nauman's socio-politicized neon signs. Holzer's work––which can also take the form of printed handouts and T-shirts––is, if anything, more deadpan than Nauman's. She merely states "truisms" gleaned and condensed from a sort of Great Books reading list of Western culture, i.e., Abuse of Power Comes as No Surprise (1977-9) in illuminated form. Less often does she venture into the imperative, as in Protect Me from What I Want (1983-5), from another series, titled Survival .

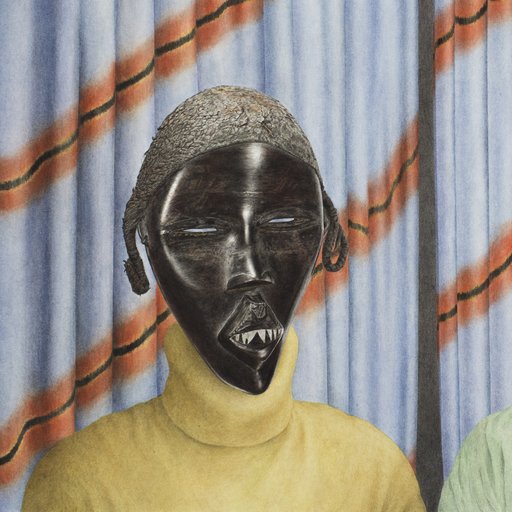

One Hundred Live and Die, 1984, Neon tubing with clear glass tubing on metal monolith, 299.7 x 355.9 x 53.3 cm (118 x 132 ¼ x 21 in). collection Benesse Corporation, Naoshima Contemporary Art Museum, Kagawa

One Hundred Live and Die, 1984, Neon tubing with clear glass tubing on metal monolith, 299.7 x 355.9 x 53.3 cm (118 x 132 ¼ x 21 in). collection Benesse Corporation, Naoshima Contemporary Art Museum, Kagawa

Nauman, on the other hand, favors the command. (Whether this is because he's male, others can decide). American Violence (1981-2) is, for instance, maddeningly unclear about what it's getting at. "Stick it in your ear" and similar impolite phrases are configured in a swastika formation and flash on and off in the medium's typical garish colors. "Stick it in your ear" is a hybrid: the usual imperative concerns a bodily orifice less conversationally polite than the ear. The customary command is "Stick it in his ear," and is a baseball fan's shout, requesting that his team's pitcher throw at the opposing batter's head. The Nazi reference in the sign's configuration is similarly imprecise, since the Nauman swastika's word-arms bend at forty-five degrees instead of ninety. The overall effect, though, is a rough condemnation of America's residual propensity for Wild-West-type violence, which amounts to a work of art slightly more political than philosophical.

RELATED ARTICLES

How did New York Change Bruce Nauman? Looking Back on a Radical Period in the Artist's Career

Jenny Holzer Describes the First Works She Made as a Young Artist––and They're Not How You'd Imagine

[related-works-module]