The irreverent Swiss artist Thomas Hirschhorn is renowned for his eclectic and energetic installations made from everyday materials and objects like cardboard, aluminum foil, tape, and plastic wrap. Created at odds with the commercial realm of graphic design and the institutional confines of the white cube, his work is often displayed in public as "monuments" to continental philosophers like Gilles Deleuze and Georges Bataille. Despite this seemingly democratic setting, Hirschhorn stresses the lack of interactivity in his work, which interrogates the audience as much as it does the capitalist structures and societal hierarchies he disdains. Existing liminally between the realms of process, installation, video, and performance art, his projects embrace their ad hoc, precarious nature to in order to, as he says, "confront reality."

Below, we’ve excerpted a conversation between Hirschhorn and the curator and critic Alison Gingerasfrom Phaidon’sThomas Hirschhorn, focusing on Hirschhorn's thoughts around being a fan, defining the success or failure of a piece, and making unpolitical political art.

Alison M. Gingeras: You first trained as a graphic designer, and later decided to abandon design to become an artist. How did that choice relate to your vision of artistic practice, which is very much engaged with notions of political commitment, and which questions the role of the artist-activist?

Thomas Hirschhorn: It was a difficult choice for me. I studied at the Schule für Gestaltung [School of Design] in Zurich. There was no proper art department, nor was it a school of applied arts like the École des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. The educational philosophy at the school was inspired by the principles of the Bauhaus, but in a degenerate and rather deviant version. Of course, it was neither the Bauhaus, nor the Ulm School, yet it adopted the precepts of both. As theorist Thierry de Duve pointed out in his book Nominalisme Picturale (1984), the very name Schule für Gestaltung implies these two affiliations both practical and theoretical.

It's important for me to stress this point, because the teaching at the school was generalized: the vague and the unsaid dominated the official discourse. Our training positioned us against the advertising industry, yet our teachers were great Swiss-German graphic designers who had worked in advertising. None of my fellow students wanted to work in advertising, but everybody knew that 95% of job opportunities were in this field. We learned a great deal about the legacy of the Bauhaus, and we were taught about the history of graphic designers, fashion designers, architects and artists. I was fascinated by Russian revolutionary artists—Malevich, Rodchenko, Tatlin, Klutsis, El Lissitzky, Popova, and Stepanova—who are still very important for me. So this was my foundation at that school, with all its intellectual vagueness, the things it left unsaid, its equivocations and institutionalized ambiguities.

But I would imagine that the school’s hybridity was an important early lesson for you. I'm thinking specifically of an education about art that also included a philosophy of its use-value.

In the midst of all that ambiguity, I always really wanted to be a graphic designer. My goal was clear. I was attracted to the use-value of the graphic designer's work. My friends wanted to become artists: they painted, they drew, they sculpted, and some actually did become artists. I didn't share their vision at this time, so I refused to take certain art classes, particularly those devoted to drawing and painting. Despite the school's philosophy, I wouldn't take those courses because I thought that as a graphic designer you didn't need to know how to draw or how to make a sculpture. An old Bauhaus principle stated that everyone had to know how to draw a pack of cigarettes. I figured there was no need to draw a pack of cigarettes—you could take a photograph.

When you left school, did you intend to give a political dimension to the profession of graphic designer?

I really wanted to work with existing images, with photographs, with texts, with forms. I wanted to find a way to confront an audience directly with my work. I wanted to work for a cause or an idea that I agreed with, to which I had a commitment. It was then that I started to claim that I was a "graphic designer for myself"—that is to say a graphic designer who doesn't work on commission, but creates for himself, independently, but also for others. To me this wasn't a contradiction. When I attended a lecture in Zurich given by Grapus, a collective of politically engaged graphic designers from Paris, I was impressed by their posters for the Communist Party, the CGT (Confédération Générale du Travail, or Workers’ Union) and cultural events in Paris. I wanted to go to Paris to work with Grapus and make posters, prospectuses, brochures. I wanted to make images with an immediate impact, to address a street public. But I thought I didn't need anyone to commission them; I wanted to create on my own.

You thought you didn't need clients?

Yes. That's where this notion of "graphic designer for myself" came from. Of course, I was completely out of touch with reality, and that's why I spent only half a day with Grapus in their studio, in spite of all the admiration that I had and continue to have for them. I realized that they too were executing the wishes of clients, even when these wishes came from the Communist Party or the Workers' Union. It was an ordinary creative graphic-design studio with its own hierarchies and clients.

They were working with the commercial model of the capitalist system. Was that the start of your disenchantment with being a graphic designer?

I started to question what to do, how best to use my forces and strengths. I was interested in working with two-dimensional forms, and thinking of how to put together existing pictures, how to design forms, cut text, crop photographs. But I dropped the idea of a being a graphic designer, living in Paris and working for myself, because I realized that graphic designers are the servants of someone else.

As a graphic designer, you are essentially someone who provides a service?

To be a graphic designer means not to be totally free and absolutely responsible for what you do. I wanted to be a graphic designer for political reasons. I wanted to be free, and responsible for my work. I wanted to be the sole author of my work. I needed a lot of time to figure that out; it was the beginning of my quarrel with graphic design. I felt I was at a dead end.

So you were trying to create visual form that had use-value, not some sort of aesthetic value?

Yes, but no one was commissioning it, no one was interested in it and I didn't have any audience to communicate with.

What happens to a graphic designer with no clients? Perhaps the ambiguity that this dilemma posed made you start thinking about making art.

I couldn't resolve this dilemma by talking with other graphic designers. They were no help to me, because as far as they were concerned art was defined by painting and sculpture. I had to find a way out of this cul-de-sac for myself. At this time I became more familiar with the work of Hans Haacke as well as that of Barbara Kruger—both of whom I found interesting. Their approaches were close to those of graphic design.

Yet their work was in a different context.

I realized that I was almost the only person in my circle of peers familiar with this kind of art. I particularly remember an exhibition by Hans Haacke at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. His exhibition was running simultaneously with a conference on graphic design there; the graphic designers in attendance hadn't even gone to see the exhibition. I was shocked! I was the only one who had seen it. There I was, in the milieu of Parisian graphic designers, isolated. I had support from my friends at Grapus who did appreciate my way of thinking, but ultimately I was on my own because they weren't interested in Haacke's work or other works of art.

Das Auge (The Eye), 2011 (installation view)

Das Auge (The Eye), 2011 (installation view)

Was it then that you began to question a political commitment based only on negation and denunciation? I recall you telling me on another occasion that there was a climate of suspicion about art in your circle. There was a consensus that art was reactionary and mainstream.

Yes.

At the same time, it seems you maintained a certain pragmatism in this early period of questioning. Perhaps this pragmatism came from your training, imbued as it was with the ideas of the Bauhaus. While you were eager to question the commercial models specific to graphic design, you were simultaneously trying to find a different political or critical model, one that wasn't based in Marxist ideology, in negative dialectics.

I realized I had to make a decision. I went on seeing exhibitions. and reading about art. I had no quarrel with the world of art—I was just outside of it. I'd seen the work of Joseph Beuys and Andy Warhol, who had both impressed me a lot, but I was still stuck in my dilemma.

So it sounds like this was the turning point in your work. When did you shift roles, and begin to feel comfortable with the notion of being an "artist?"

Basically my transition to "artist" took place over several years. First of all I had some important encounters—not with artists, not with graphic designers, but with intellectuals. However brief these encounters were, they put me in contact with people who helped me to take my trajectory seriously. They helped me to understand that my choice was political, not artistic, that I was refusing to become an artist for confused reasons. I was denying art on the grounds that I found it too navel-gazing or too technical. The fact was that I simply found art too formalistic. I realized that I had to make the choice to be an artist because only as an artist could I be totally responsible for what I did. The decision to be an artist is the decision to be free. Freedom is the condition of responsibility. I realized that to be an artist is not a question of form or of content, it's a question of responsibility. The decision to be an artist is a decision for the absolute and for eternity. That has nothing to do with romanticism or idealism, it's a question of courage.

During times of crisis, people often need to look for role models. In my time of crisis, I read about artists—Joseph Beuys and Andy Warhol in particular. I also read about Otto Freundlich and Piet Mondrian. These were artists who had spent their lives being true to an initial idea. Their work wasn't just to do with formal concerns. The best example for me was Warhol. I'd seen the exhibition at the Fondation Cartier, Jouy-en-Josas, "Andy Warhol System: Pub, Pop, Rock" (1990). It was at that point that I understood that throughout his whole life Warhol remained true to what he had been at the outset. He never deviated from this initial approach. This said a lot to me. He understood that he didn't have to be either a painter or a sculptor; he understood that commercial graphic design fell under the heading of "illustration." Having grasped that, he just developed, repeated, industrialized. It was that understanding that gave his work all its formal strength, and introduced a critical dimension.

Warhol's work also revealed a sense of humor. He had a conflated view of the notion of high and low culture, such as you developed in your own work later on.

That's why Warhol is important to me. He stayed true to that little drawing of shoes that he had colored in gold. His approach helped me when I was questioning myself. When I made the decision to become an artist, and to break with the world of graphic design, I understood that from that moment onwards I had to stay true to what I was looking for. I chose to be liberated from the constraints of format, material and support.

From your very first works up to now, you've questioned the categories of "sculpture" and "installation." You often use the term "display" to describe your first artworks. It seems this was a bridging term between your work as a designer and that as an artist. Works such as Fifty-Fifty (1993) or Très Grand Buffet (1995) fall into this category: they're essentially two-dimensional pieces that combine text, image, and flat objects. Is that a kind of continuity with your earlier principles, now displaced into another context?

From the moment I worked on a sheet of paper, on cardboard, or on other easily available materials, I wanted to do it with a two-dimensional spirit. This implies that I can look at it from all directions, that it can be turned any way up, that there's no directed reading. I wanted to do a three-dimensional work in a two-dimensional-spirit—not to think about the volumes. I was never interested in volumes, weights or the dynamics of forms.

But it also acquires the status of an object?

It becomes something else, like a map. All of a sudden another dimension appeared—not a dimension that I had created, but a dimension that made a vision possible. That's why my earliest works, such as the "displays," were conceived as though they were being perceived by a pilot in a plane, who can make out shapes from above the earth. In fact, it was a post-post-supremacist vision. As my ruminations on the question of how to show my work became urgent, I understood that I was abandoning the format of the A4 page, books, and other elements of graphic design to which I had at first limited myself, while also making a clear choice not to make drawings or paintings. I still had to come up with an alternative to these.

This is where the idea of the "display" or "lay-out" presented itself: how to present my work, not like a product or as an object, but something in process. I borrowed these terms from graphic design so as not to refer to the history of painting or drawing. The term is supposed to indicate something other than a finished product. When I say "display," it's something banal, unspectacular, like something in a shop window that's just put there. At the same time, you can also look at a shop window from behind, from all sides.

If I've understood correctly, this early work could be read as a partial critique of the autonomy of sculpture, as well as the term "installation"—which has dominated recent art practice, often replacing the category of sculpture. But this critique was born out of a genuine pragmatic drive: your desire to be faithful to your beginnings as well as to a certain aesthetic that was part of both your graphic and artistic practice.

I was visiting galleries and museums, and already had a critical attitude towards the "white cube" and towards glorified, mystified artworks and the means of displaying them. I always hated a certain way of presenting artworks that aims to intimidate the spectator. Often I felt myself excluded from an artwork by the way it was presented. I hate the suggested importance of context in the presentation of artworks. From the outset I wanted my works to fight for their own existence, so I wanted to put them in a difficult situation. My early works were intended to be a critique of what I was seeing; I didn't want to imitate what I was criticizing, I wanted to try another way.

Très Grand Buffet, 1995 (installation view)

Très Grand Buffet, 1995 (installation view)

This brings me to the question of the materials you consistently use in your work. From the very beginning through to your most current works, you've used banal and ephemeral materials such as cardboard, packing tape, aluminum foil, Plexiglas. Looking at your vocabulary of materials, it's tempting to project the notion of "precariousness" on your works. These materials are all very cheap; they share a functional role in our society as "wrappings" for commercial merchandise that ultimately becomes the refuse of consumer society. Was the choice of these materials essentially pragmatic? Was it part of the struggle that you wanted to set up in relation to the status quo of the art world?

The issue of the choice of material is political but it's also pragmatic. Joseph Beuys said, "I work with what I've got, what I find around me." In my case, I don't have fat or felt, I don't have sandblasted glass around me; nor am I surrounded by gold and marble. I haven't got a big light box. What I've got around me is some packing tape; there's some aluminum foil in the kitchen and there are cardboard boxes and wood panels downstairs on the street. That makes sense to me: I use the materials around me. These materials have no energetic or spiritual power. They're materials that everyone in the world is familiar with; they're ordinary materials. You don't define their use in advance; they aren't loaded. There's no doubt, no mystery, no surplus-value. I have to like the material I work with, and I have to be patient with it. I have to like it in order not to give it any importance. And I have to be patient with it in order not to give myself importance either.

You can't project a mythology on to them, unlike with Beuys’s use of fat?

These are materials that don't require any explanation of what they are. I wanted to make "poor" art, but not Arte Povera. My work has nothing to do with Arte Povera. Because it's poor art, the materials must be poor too: quite simply, materials that make you think of poverty. To make poor art means to work against a certain idea of richness. To make rich art means to work with established values; it means to work with a definition of quality that other people have made. I want to provide my own definition of quality, of value and richness. I refuse to deal with established definitions. I'm trying to destabilize them. I'm trying to contaminate them with a certain non-valuable aspect of reality. The value system is a security system. It's a system for subjects without courage. You need values to ensure yourself, to enclose yourself in your passivity and anxiety. You need the idea of quality to neutralize your proper freedom: the fact that it's you who decides what's valuable or of worth. People need quality as a kind of ghost who helps you escape the real. To make poor art is a way to fight against this principle. Quality, no! Energy, yes!

So the reference to "poverty" in your work operates on many levels. The association, for example, with the homeless person on the street corner who builds a little cardboard shelter—is that a deliberate and direct reference in your work too?

All of the materials I use have some local or vernacular usage: the aluminum foil you see in rural discos; the photocopies you see stuck up on university noticeboards; the packing tape you see everywhere; the wood and cardboard I can find on the street; the cheap reusable paper is very common. All those possible associations—from drugs bagged up in plastic and tape, to the cheap suitcase that bursts at the airport and which you quickly tape up—all those local or vernacular references are deliberate. It's a political choice.

In this context, I've always thought that an exclusively political reading of your work neglects an important part of your practice. Despite the absence of mythology in the materials you use, they nonetheless help to underscore the self-effacing, humorous perspective that you have with regards to your role as an artist. An example of this is one of your earliest works, the performance entitled Jemand kümmert sich um meine Arbeit (1992), "someone takes care of my work." You placed a number of your sculptural objects on the sidewalk, and then documented the sanitation workers throwing them in the bin. By placing these works in an awkward position—where it was very hard to differentiate them from the general garbage—was a laconic way of positioning yourself as an artist.

I said to myself, "If my works are like canvases by Picasso abandoned on the street, perhaps the passer-by won't throw them away. He might say, ‘That's beautiful, I’ll take it home and hang it up, it's like a Picasso and it's valuable.’ He might say that—or not." At that time my works had no market value—in fact, these works come from a series that I still own. But what I'd put on the street wasn't exactly rubbish either. My aim wasn't to put the person who came across the work to the test. Instead my idea was to hold an exhibition with active spectators, hence the title. Filming the action was like documenting an exhibition. Even if everything ended up in the bin, it was the same as exhibiting in a gallery or a museum to me.

[related-works-module]

Just as humor is an agent that activates the political meaning of your work, I wonder if the recurrent use of collage is also intended to emphasize a political will? Your collages articulate very clear political commentaries, without being devoid of humor. They also seem to refer to the politicized tradition of collage in art history, in artists such as John Heartfield and Aleksander Rodchenko, whom you doubtless studied in art school.

Collages, from those of Heartfield to those of Kurt Schwitters and others, made a big impression on me, mainly because those artists worked only with what they had within reach. I always liked making collages. I liked bringing together what shouldn't be brought together. The stronger the contrast, the better it was. I liked that material constraint and I liked the easiness of making collages. I liked their "stupidity." I tried to ensure that the message was immediately apparent. As students we were always encouraged to go beyond the Rolls Royce juxtaposed with the hungry Third World child. It took me a long time to understand that the really important thing was the Rolls Royce juxtaposed with the hungry Third World child!

The action of putting together two things that have nothing to do with each other is the principle of collage—that's where the politics lies. In today's society meaning is diluted by an overload of information as well as the tendency to over-explain everything. We're getting further away from the Rolls Royce and the hungry Third World child. There are examples in Heartfield's work that showed the same direct, brutal juxtaposition process. Heartfield said, "Use photography as a weapon." But if it is a weapon, you can blow your own head off with it—it's just as dangerous for you. You can define philosophy and art as the search for your weapon. It's a question of how to arm yourself while fighting against the established power. Philosophy and art are machines de guerre. I like this. A war machine is a tool with which to struggle for freedom, to territorialize yourself, to get out of the whole shifty art, culture, power system. There's nothing new, no creation, no action without this machine de guerre. Art and thinking result in permanent self-mutation, self-deconstruction, and self-mutilation. You have to overtax yourself again and again.

Can you talk about the moment you decided to exhibit your works in a public space?

At that time I was having discussions with friends who were very critical of the "system," of museums, and of galleries.

I can imagine that the assumption was that the art shown in those places were corrupt a priori.

They were preoccupied with the fact that art in galleries and museums had become institutionalized. From the moment I decided to be an artist it was clear that, along with my choice of materials, how and where I presented my work would be important. I realized that, as an artist, I'd have to show my work in museums and galleries. But I also tried to show it in public spaces or in alternative galleries or in squats, in apartments, in the street. I wanted to be responsible for every side of my work. That's what I call "working politically," as opposed to "making political work." I wanted to work at the height of capital and the height of the economic system I'm in. I wanted to confront the height of the art market with my work. I work with it but not for it.

Overall I confront people with my work both in the museum and on the street. From the very beginning I've tried to head in these different directions simultaneously. The work comes first; where to exhibit is secondary. This is my guideline. Of course, early in my career I wasn't given the opportunity to show in a museum or a gallery anyway, but I did exhibit in public spaces. I've made more than forty projects in public spaces, so my work hasn’t moved from the public space to the museum, nor from the museum to the public space, but towards all these places at the same time.

So you have no sense of a hierarchy in terms of exhibition spaces and opportunities?

I do hate hierarchy, every hierarchy. In discussions with other artists, I've always felt quite alone with this position. In the alternative venue called Zonmééé, in Montreuil, where I worked for a while, there were many discussions about hierarchies, strategies and about fighting against the museum, the system, the market, the institution. I never really understood the critique of the institution. It's important to stress that I've never based my work on institutional critique or the critique of commerce. I don't want to fight against; I want to fight for. I want to fight for my work. And through my work I want to confront the audience, criticism, the market, the institution, the system, the history, but it isn't an end in itself.

This brings us to a notion that recurs in all your works. It seems that you systematically integrate a certain form of struggle in your art. But there must be a difference between the way struggle is integrated in a work conceived for public space and a work conceived for a closed space, a commercial space, or a museum context. Can you talk about strategic and formal changes in the conception of your work in relation to context?

There is no change. There are basically things that work better in a museum or in a gallery or on the street. For example, in public space the "precariousness" you mentioned is more intense because the project is subject to weather and vandalism. But for me it's only about scale; inside the museum is almost equally as precarious as outside on the street. After all, the Egyptian pyramids are precariously out in the open! I like this term "precariousness"—my work isn't ephemeral, it's precarious. It's humans who decide and determine how long the work lasts. The term "ephemeral" comes from nature, but nature doesn't make decisions.

We're not talking about Process art.

No. That's another reason why I don't use different materials in the public space and the museum. The public doesn't change. For me, the context doesn't change the work, because I want to work for a non-selected audience. What changes is the opening hours. In public space, the exhibition is open 24 hours a day.

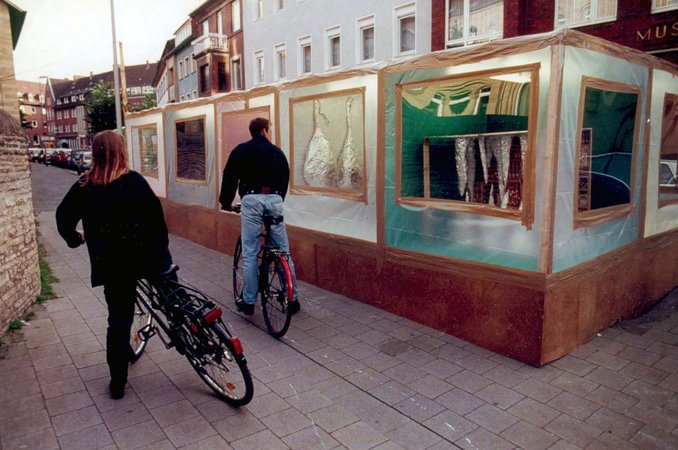

Skulptur-Sortier-Station, 1997 (installation view)

Skulptur-Sortier-Station, 1997 (installation view)

Yet I've noticed a sort of evolution or shift in the works you make for public space. For example, earlier works such as Skulptur-Sortier-Station in 1997 at the Skulptur Projekte Münster, or VDP—Very Derived Products at the Guggenheim SoHo (New York, 1998), or the work in Bordeaux, Lascaux III (1997), all took the form of closed structures, or "vitrines" that the public could look into but not physically enter. Some of your more recent works, such as the Bataille Monument for Documenta 11 (2002), or the project in Aubervilliers, the Musée précaire albinet (2004), are structures that the public can use, enter, occupy and animate.

In my two last public-space works, the Deleuze Monument (2000) and the Bataille Monument there is certainly a development. Clearly there's a difference between a piece like Travaux abandonnés on La Plaine-Saint-Denis (1992) and the Bataille Monument in Kassel. The difference is the scale on the one hand and the possibilities of implication for spectators on the other. But I'm not an animator and I'm not a social worker. Rather than triggering the participation of the audience, I want to implicate them. I want to force the audience to be confronted with my work. This is the exchange I propose. The artworks don't need participation; it's not an interactive work. It doesn't need to be completed by the audience; it needs to be an active, autonomous work with the possibility of implication.

With projects such as the Deleuze Monument and the Bataille Monument I wanted to multiply the possibilities of implication. Before, when I made larger-scale works—I'm thinking of the work that I made in Langenhagen, the Kunsthalle Prekär (1996), the M2-Social, in Borny (1996), and later the Skulptur-Sortier-Station in Münster and Paris (1997)—I was creating closed structures. There was no possible implication for the spectator other than thinking—which is of course the most important activity an artwork can provoke, the activity of thinking.

So the issue was confrontation rather than some sort of participation or supposed "community" activity, as suggested in the relational theory of Nicolas Bourriaud, which emerged as a model about the same time as your early public work and had some claim to political meaning.

Confrontation is key. You get that again in the altars (1997–98), in the earlier projects such as Travaux abandonnés, and even in Jemand kümmert sich um meine Arbeit, in which there was already the will to confront. I've always thought that the work of art exists even if no one looks at it. It doesn't exist only in relation to someone. Because if a work of art only exists because someone uses it or employs it in some way, there's a non-will that I reject. The artist has to take the responsibility for the artwork, including responsibility for its failure. This criterion was applied to Skulptur-Sortier-Station when I installed it under the Stalingrad Métro station in Paris (2001). The critics said it didn't work because it had no use-value. This reproach never bothered me.

With an artwork in a public space it's important to provide the choice not to see the work or not to use it. It's important to provide the possibility of ignoring the artwork. Because just as an artwork in public space is never a total success, it's never a total failure either. Anyway, it doesn't need this criterion of "success" and "failure" in order to function. What I'm criticizing about participatory and interactive installations is the fact that the artwork is judged as being a "success" or "failure" according to whether or not there's participation. I now see this kind of work as totally delusional, although I did make a work in this participatory vein, Souvenirs du XXème Siècle, at the Pantin street market in 1997.

This work took the form of a sort of market stall where you sold different things you'd made such as T-shirts, mugs, banners, and football scarves with the names of artists on them.

Yes. That project was deemed a "success" because we sold the lot. But let's be honest, about 90% of the objects were bought by people I knew, collectors who knew that this was an art project by me. Then there were about 5 to 8% of people who were passing through, who might have known Deleuze or liked Mondrian and bought a mug for that reason, without knowing it was my work of art. Only 1 or 2% just bought them for no reason other than because they needed them and they were cheap. I was certainly aware of the unreality of my project, but this 1 or 2% is still important. The danger with these types of projects is to think that it's a success when it's actually a failure. So I'm suspicious of the interactive side of art projects. It's important not to fall into the trap of "success." What I'm criticizing is the idea that failure isn't accepted, that it's hidden. I wanted to stop hiding failure, stop hiding the fact that I might be wrong.

So there's never any preconception of what the spectator's participation will be, even if your work has developed away from closed sculptures towards more open sites? Your recent series of monuments in Avignon or Kassel—where inhabitants of the community where the works were installed were directly invited to participate—created a social environment that involved the participants maintaining or animating the work. It seems as if you cannot avoid creating some sort of social contract in these works.

With the monuments, the only social relationship I wanted to take responsibility for was the relationship between me, as the artist, and the inhabitants. The artwork didn't create any social relationship in itself; the artwork was just the artwork—autonomous and open to developing activities. An active artwork requires that first the artist give of himself. The visitors and the inhabitants can decide whether or not to create a social relationship beyond the artwork. This is the important point. But it's the same in the museum. The idea of success and failure is also present in the museum: a lot of visitors pass in front of the artwork, but what is the visitor's implication? Yet people want me to subscribe to this shabby "contract" with my projects in public space. The Deleuze Monument and the Bataille Monument were much more: they were experiences.

So there's no ambiguity when you create a social contract, because there's no fiction behind it. You're not creating a predetermined, fictional political act?

There is no fiction. There's reality and my will to confront reality with my work. Art exists as the absolute opposite of the reality of its time. But art isn't anachronistic; it's diachronic. It confronts reality. As an artist, I ask myself, am I able to create an event? Am I able to make encounters? With the last monument project I understood more and more clearly that it's important to assert the complete autonomy of the artwork.

Touching Reality, 2012 (video still)

Touching Reality, 2012 (video still)

So it's a matter of suggesting things to the inhabitants of the place in which the installation is made without having any preconceptions about them?

The Spinoza Monument (Amsterdam, 1999)—the first monument I made—already had all the elements I used in the later monuments: the sculpture, the photocopies of selected texts, flowers, a video I'd made, books that you could consult. It was small, compact, and concentrated. It was lit day and night thanks to a cable plugged into the sex shop opposite, which supplied me with electricity. It was located in Amsterdam's red-light district. I thought it was pertinent for it to be placed there. It provided a kind of nexus of meanings. But I thought that some elements could be more active, more exaggerated, more intrusive, more offensive, more present, more overtaxing to myself, and I wanted to be more involved in order to increase confrontation. I wanted to develop these aspects with the subsequent Deleuze Monument and Bataille Monument.

So this desire for more intrusiveness gave rise to the works’ potential to be "inhabited" by people? This habitation wasn't necessary for their existence; they didn't really need to be activated by the public, it was just part of taking it to another level?

The work only provides the possibility of activation. It wasn't necessary that it should be activated—neither for the work nor for the spectator. Yet there was this possibility. The confrontations in the Deleuze Monument and the Bataille Monument were dense. They were pertinent experiences that raised many questions for my future works regarding the presence of the artist, paying the inhabitant for their work, the creation of libraries. Such projects have an aesthetic that goes beyond art towards service; it loses its strength as an object.

The autonomy of the object is sacrificed in favor of activism?

The Bataille Monument develops other strengths through the fact that it can be "used." There's no "sacrifice in favor" of anything. The will to confrontation and the assertion of its autonomy works!

The monuments have no use-value or didactic mission, even if they often have libraries, videos, television studios? I think people are likely to read this element of these works as some form of artist-activism, as your desire to spread the word of these philosophers.

There is no "use-value," it's about absolute value. It's too vulgar and too easy to communicate the work of philosophers; there's nothing to communicate about artists, writers, or philosophers.

So you just give a clue by providing a library?

The entire monument was one form with different elements; the library was one element of the monument. I didn't "provide" the library; I'm not a politician and I don't represent anything, but I did give form to the library. I want to give form—I don't want to make form. I give a form, my own form, and I only want to represent myself. I wanted to assert my love for Gilles Deleuze or Georges Bataille. I want to give form to this love. And I do think love can be infectious.

There's a parallel between the monuments—and the altars. In both you use proper names in the titles: Mondrian, Deleuze, Bataille, and Spinoza, to list a few that are recurrent in these works. Why these names? you've mentioned in the past that these are people whom you appreciate, but you're clear about them not being heroes for you. Aside from being figures who’ve taught you something, I also wonder if you aren't seeking to allude to the exchange value of those names: the way they signify intellectual capital in our culture. You play a lot with those notions, and the kind of "devotion" that they provoke.

That's very perceptive of you. Obviously what interests me about Deleuze and Spinoza is the value of their work, but not as an "added value" that I integrate into my work. If I love Deleuze or Spinoza it's because of the absolute value of their work, because they give me strength—I need them as a human being!

Deleuze Monument, 2000 (installation views)

Deleuze Monument, 2000 (installation views)

And what about Ingeborg Bachmann?

I chose her for her writings, for her magnificent poetry and for her beauty. Her work manifests itself as an exchange value in the sense that I assert that I'm a fan. I am a fan of Ingeborg Bachmann. I give something, I uncover myself, I assert. The fan decides on his attachment for personal reasons. These reasons could be geographical in nature, or have something to do with age or occupation. I like that idea. you've perceived this aspect of what I'm saying when you use the term "exchange value." I made the monument series about people I'm a fan of. Someone else would have made a Michael Jackson Monument.

The fan isn't obliged to have a professor's knowledge. This is an important distinction. I've heard people making critical comments about your work along the lines of, "Thomas has not read all the works of Deleuze or Bataille."

Of course I haven't! I've only read a few books by Georges Bataille. But I read, for example, what he wrote about an "acephalous society," one that's headless, stupid or silly, in German: kopflos. I really like that "headless" idea. I made the Bataille Monument because of Bataille's book La part maudite (1967) and his text La notion de dépense (1933). It's not about being a historian. It's not up to me to be a scientist. This isn't scientific work, it's an artwork in relation to the world, which confronts reality, which confronts the times I live in. I've never claimed to be a specialist, or even a "connoisseur." I'm a fan of Georges Bataille in the same way that I could be a fan of the football club Paris Saint-Germain. I'm not obliged to go and see all the matches. I'm not obliged to know the whole history of Paris Saint-Germain football club. You can even be a very fickle fan: when a fan goes to live in Marseille he can become a fan of Marseille's football club; he's still a fan. That's why I like the term "fan." The fan can seem kopflos, but at the same time he can resist because he's committed to something without arguments; it's a personal commitment. It's a commitment that doesn't require justification. The fan doesn't have to explain himself. He's a fan.

[related-works-module]