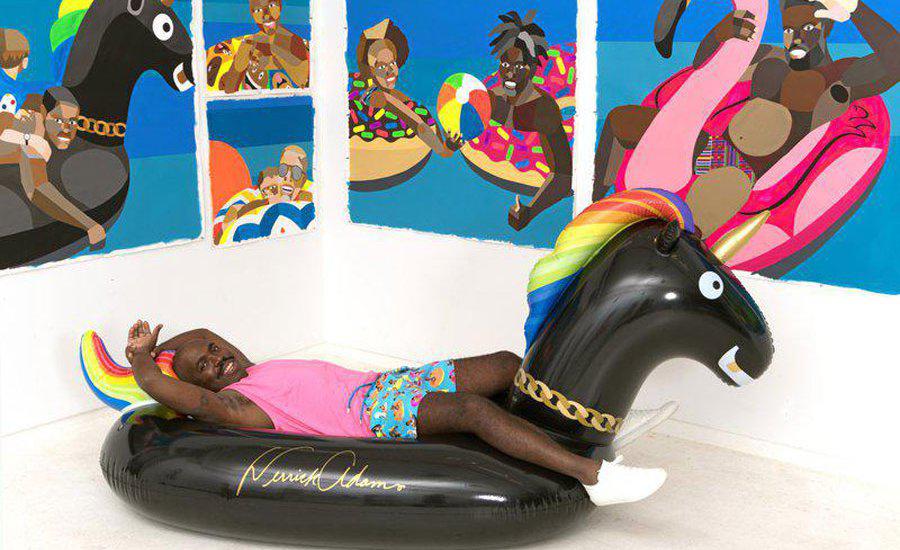

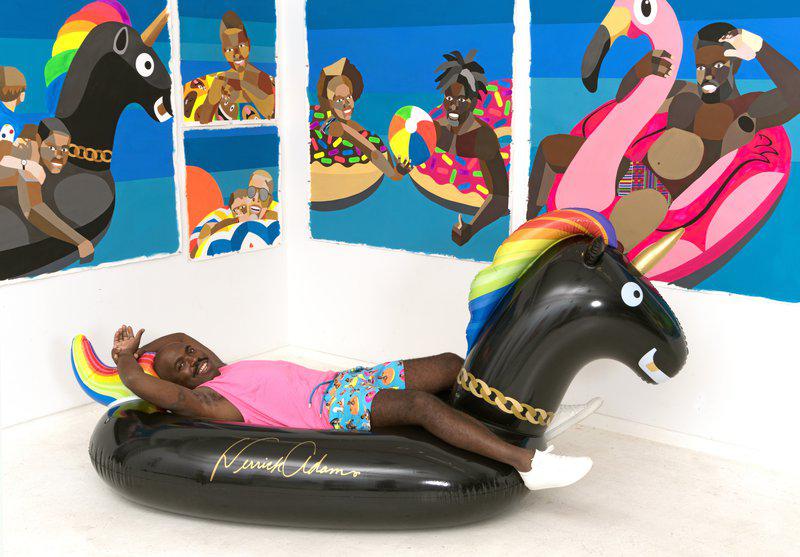

News of a collaboration between a fine artist and a swimwear company might give you cause to raise an eyebrow or two. However when the artist in question is Derrick Adams and the swimwear brand is the decidedly upmarket Vilebrequin, it begins to make a lot more sense; a perfect positioning even. Adams' Floater series - a collection of bright and breezy paintings depicting African American men, women and children lounging on whimsical pool floats - are the visual basis for the collaboration.

The Floater series received its first museum outing this year as part of a larger retrospective of Adams' work at the Hudson River Museum. The artist has worked with the brand to use the images on swimwear and tote bags designed for beach and pool. We asked him how the collab came about, where the Floater series images originally came from and where he’ll choose to go floating himself when the pandemic is eventually over.

First of all, how did the collaboration come about Derrick?

Funnily enough I was in the studio one day working on the Floater series of paintings - basically black figures in a leisurely stance which I first started work on in 2015 - and I said out loud that I would love to make these into swimwear. And maybe a week later I got an email from Vilebrequin out of the blue. I thought it was like junk mail at first because it was so weird as I had just been talking about it. When I reached out to them that was exactly what the invitation was - to collaborate on swimwear.

So we met and talked. And I told them about the idea I had. I’m coming to the end of the Floater series and as a finale I wanted to create an object that would be more accessible to a larger audience of people, beyond the unique artworks that go into galleries and museums and collections. I felt that adding an element to my practice by making a wearable art piece would just reach more people and be more of an offering and in a different kind of way. So I was excited and made a proposal to create this pattern and create a trunk.

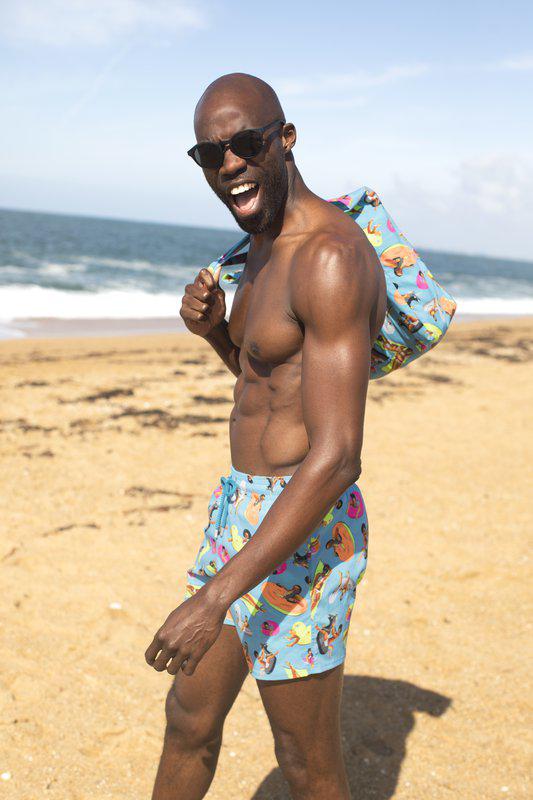

Vilebrequin X Derrick Adams Moorise swim trunk

Your friend and fellow artist Mickalene Thomas described the Floater series as “capturing the essence of black joy that most people don’t necessarily witness”. It’s a great encapsulation, isn’t it? Yes it is. The original intention for the Floater series was to make something that has a certain level of lightness and joy but coming out of somewhere or something that I felt was missing.

I think that most of my practice comes from a serious and very focused point of view. But I hope that the outcome is not as weighted as some of the motivation for making it is. The focus of a lot of my work is to normalise things that are not necessarily seen to be normal. So the Floater series originally came out of that. But having the swim trunks makes it more of a statement about community, accessibility and connectivity in a way that an artwork necessarily cannot.

Your wider artistic practice is partly about reconfiguring things, so this collaboration could be seen as not too far out from that essentially deconstructivist approach of yours, couldn’t it? It’s a perfect joining! One of the ideas that came to mind when I had this idea, using this pattern for swim trunks, was that I thought it would be best presented with a brand that’s respected as a swimwear line, as opposed to just putting my image on some trunks. It was really more about a union between myself and a respected swimwear brand that had a certain level of quality that I felt related to the way I make work and the way I present work. So I felt that it was almost like fate.

The often used description of the Floater paintings as ‘joyful’ and ‘positive’ comes with a certain degree of irony though, doesn’t it? One of the things that is important about the work is that the idea of positivity comes up a lot when people discuss it. And I think that is an ironic point of view. Because the idea that positivity has to do with some type of opposition of seeing something different, and the fact that people consider it positive, shows that that is a problem in itself. To me that is really an interesting thing, because if the figure was of a different cultural background, maybe the idea of looking 'positive' wouldn’t necessarily be in the conversation. I think that there’s room for other more related narratives and other depictions of black lives that are not seen as being as radical. But I think that representing these images in the context of leisure does present an idea of being radical because it’s something that people have to contemplate - its meaning and purpose and what exactly is it doing for the viewer.

The idea of pushing art into the mainstream and into areas where it would not normally be present is obviously an important one for you. Totally. My goal was always to make these images so common place that when I’m finished with the series it would somehow influence another generation of visual artists, to contemplate on how to depict themselves culturally and allow them to think about other more personalised representations of who they are and what they represent.

I feel we sometimes as people don’t look at it as radical or as necessary to put the most mundane things into the world. But the idea of the mundane, or of not doing anything in particular, doesn’t necessarily reflect a sense of not thinking, or of not moving forward. Sometimes you have to have those moments of reflection, and of leisure, in order to have complex ideas and to really think about life.

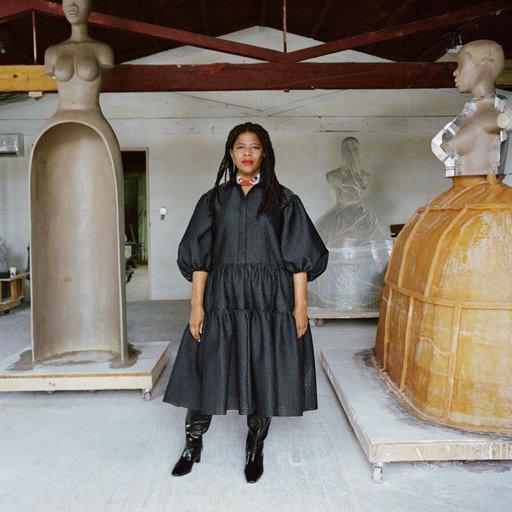

Vilebrequin X Derrick Adams Balade tote

Vilebrequin X Derrick Adams Balade tote

Getting back to what you said at the beginning, what made you think you were coming to the end of the Floater series? I’d put over a hundred works into the world from the series and I feel like I’ve said as much as I can say about the subject. I’m hoping the influence of seeing these works in the world will be significant enough to influence other people to follow suit in some ways and to take more agency over how they want to be represented in the world. Again, as artists we do have the opportunity of creating things I feel are necessary for the younger generation to see in the future.

For me I feel that I have so many other narratives to explore. This was just one small one out of all the works I’ve made. And I’ve always worked on various series at the same time and now I’m just departing to focus on other challenges for me creatively. I really want to explore formalism, because content is something that will always be a part of my practice.

The quality of formalism is always kind of based on work and practice and exercise and those things. And so I’m really excited about moving forward and having some more experimental projects to take on that will have conversations that are not away from the Floaters but maybe something that can extend that conversation into another aspect of black life. If I had to say anything about my practice it’s probably an extensive book with many different chapters. Many and various themes that are related to one common goal!

OK, where do you think you’ll go floating when this pandemic is over and we can alll breathe a sigh of relief?

I’m very close to my family and they have a place in Sag Harbor in New York. It’s on the water and so every time I get a moment I go there and have some family time - plenty of water, and a pool, and a beach. I like to float when I’m there. That’s what I enjoy.

Take a look at Derrick's artist page to see the Vilebrequin collaboration as well as many other fine works by him.

Derrick Adams kicks back in Vilebrequin