Since some of humanity's earliest artworks, the nude has been an art form betrothed to passive figures of women, often meant to tantalize and seduce the (assumed) male viewer, or to embody idealized notions of athleticism and power in the male figure. It wasn’t until the first rumblings of Modernism at the end of the 19th century that some painters began expanding the subject beyond objectification, instead empowering their subjects to take active roles. Still, the nude has largely remained chained to the male gaze, though this is quickly changing as feminist ideals of vulnerability and politics of the body penetrate the art world, making for more critical modes of representation. Below we’ve chosen three painters with distinctly contemporary takes on the nude, as featured in Phaidon’sVitamin P3.

JANA EULER

Born 1982, Friedberg, Germany. Lives and works in Brussels.

Jana Euler’s first institutional solo exhibition, held at Kunsthalle Zurich in 2014, was titled after her series “Where the energy comes from” (2014), three larger-than-life paintings depicting non-regulated sockets from different European countries. Anthropomorphic and anachronistic, the group might at first glance seem to fall into the category of anatomic metaphors made (in)famous by Blues musician Muddy Waters in the 1970s when he recorded the not-too-subtle song Electric Man. Yet the decision to situate the paintings in the final room of the show opened up another, more poignant interpretation: a celebration of the energy source that made the art on display possible, as well as a hint at the element of participation required of the viewer in order to experience it. The contradiction of having non-standardized sockets, signifying a stubborn resistance to conformism, versus the obvious need for a third party to implement their activation, was best described by Euler when she expressed a desire for the verb “to socket” to exist, along with the possibility of a “Manifesto for Vulnerability”—an apparently fractured statement but one deeply resonant with her art. In their less esoteric moments, Euler’s portraits of women are an exquisite combination of fragility and empowerment.

Turning “socket” into a verb is admittedly a task out of Euler’s hands, but writing a manifesto for vulnerability is a different proposition, as her self-portraitNude climbing up the stairs (2014) attests. Taking its cue from Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (1912), the painting functions as a self-portrait, and is an example of how a simple intervention like switching the subject’s body can alter the reading of a canonized image. Viewed from a frontal perspective, and defined by a stronger realism that makes the figure easily identifiable, Nude climbing up the stairs transcends its original muse to bring to the fore issues of objectification and voyeurism. The reversion from descension to ascension introduces a narrative, too: removing the focus from the motion itself to the place where the motion leads, piquing the viewer’s curiosity to follow and find out what might lie upstairs.

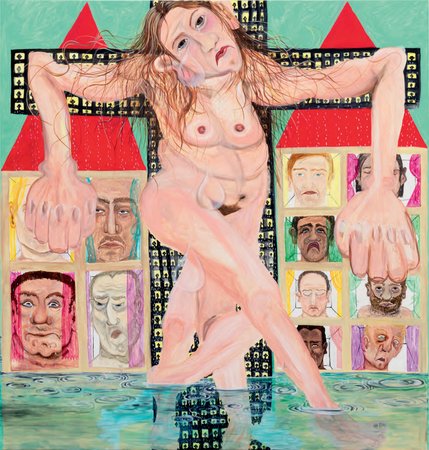

Female Jesus crying in public (2015), the centerpiece of Euler’s 2015 exhibition at Galerie Neu in Berlin, further investigates the way women are represented in art by reprising the language and the compositional structure of classic Gothic iconography. Surrounded by an arena of portraits of visibly subdued men, some sobbing, some averting their eyes, a crucified woman literally drowns in her own tears. This tragically public demonstration of suffering is underscored by the addition of three sets of airplane seats aligned in front of it. The painting is a spectacle, but not one that can be enjoyed in mindless comfort. The erosion of conventions does not make for a pretty sight. Euler has made clear how she feels about having to work under constant scrutiny since her 2009 exhibition at the gallery Pro Choice in Vienna, when she illustrated the chore of professional networking through a pantheon of contemporary art celebrities. Brutally direct and yet perfectly in line with the gothic tradition it perpetuates, Female Jesus crying in public is a powerful reminder that the act of looking is both emotionally enriching and taxing.

– Michele Robecchi

CELIA HEMPTON

Born 1981, Stroud, UK. Lives and works in London.

A plump bottom lies before us on a cloudy-white bed sheet. Slightly raised, two cheeks protrude, while two testicles peek out from underneath. The rounded figure is rendered in broad brushstrokes of aquamarine, orange, and pink. The painting is entitled Eddie, August 2013, Hotel Lumin, Dallas (2013), after the name and location of the male sitter. Like many of Celia Hempton’s subjects, Eddie is observably posing, but it is a posture of vulnerability—passive, objectified, the subject of our gaze. This work is one of dozens of paintings produced in various scales and sizes, from the miniature to larger than life-size, of male figures whose bodily features—a flaccid Technicolor penis or an erect one—collectively portray the divergent forms of modern day gender, sexuality, and performance. Most evocative here is how the artist manages to both capture and flatten the attitude adopted by her subjects, revealing the manner in which each figure’s posturing is suggestive of a kind of performance. As the artist has stated, “what I am looking for when painting is a situation more important than painting itself.”

The performative turn is also explored in Hempton’s “Chat Random” (2014–ongoing), which sees the artist painting live whilst using the website chatrandom.com, a social networking platform facilitating randomly-connected video chat with other users of the site. These users are visible inside a small window on the computer screen, identified by their location and occasionally a username. Hempton meets strangers online and asks them to model for her whilst continuing the conversation. Chatrandom.com, like the site chatroulette.com, began with an idealistic notion that it could offer a universal platform for human interaction but has since largely grown into a site used for sexual exposure. Serving partly as painterly documents of the artist’s encounters, the “Chat Random” series also acts as a meditation on the changing nature of painting. Here, it is as an accelerated process of daily performance whose practice is driven by the digital obsession for live-ness: Hempton only paints for as long as she can hold the conversation; once her interlocutor has moved on, she stops painting and moves on herself.

The Internet is an ongoing place of research for Hempton, who most recently has begun unearthing archives of human trauma, such as hangings and beheadings. Hempton re-imagines these events in lurid and haunting colorful bursts of paint on canvas, placing emphasis on the body as a political border. Indeed, Hempton’s work is most concerned with the haptic possibilities of the body, both still and in motion. It is the interface by which we experience all emotion, and for Hempton it is the most fragile and urgent object of study.

– Omar Kholeif

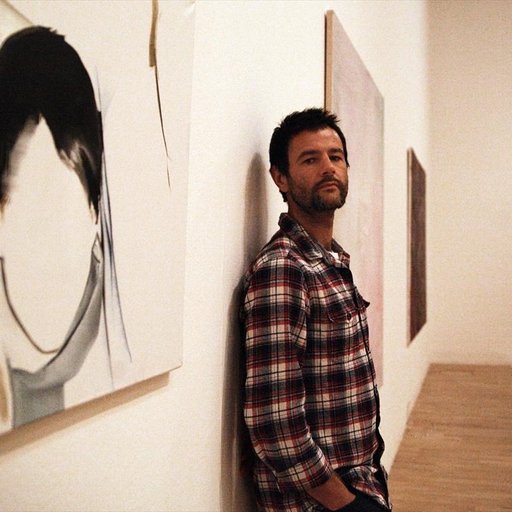

PATRIZIO DI MASSIMO

Born 1983, Jesi, Italy. Lives and works in London.

Painting is not the only medium Patrizio Di Massimo is well acquainted with. Although he fell in love with the work of Picasso (1881–1973), Giorgio de Chirico (1888–1978), and Salvador Dalí (1904–1989) when he bought his first modern art book as a teenager, Di Massimo’s early efforts were mostly executed in video, photography, and performance. One of the first, timid appearances of painting in his work took place in a group show at FormContent in London in 2008, where he exhibited a small charcoal on canvas depicting a profile of a head on a plinth—a work that in the darkness of the room could have been easily confused with the brick wall on which it was hanging, were it not for the slim wooden frame around it. This early demonstration was followed a few months later by a more imposing, albeit completely different presentation, this time on an actual plinth, of an apocryphal painting by Mario Schifano (1934–98) purchased at a flea market in Rome. A subsequent trip to Libya, Schifano’s home during Italy’s ill-fated experiment at imperialism, resulted in a series of drawings inspired by colonial iconography; but it wasn’t until 2009 on the occasion of his degree show at the Slade School of Art in London—when Di Massimo showed a series of male figures loosely adopting fascistic mannerisms next to one of women and aptly named after Picasso’s aphorism (“As every artist I am first of all a painter of women”)—that painting began to claim a central role in his practice.

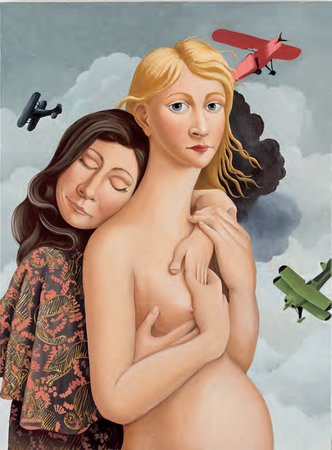

Di Massimo’s combined interest in personal and collective history, along with a soft spot for the twisted side of things, is the driving force behind his largest body of work so far. The Lustful Turk (2011) is a group of paintings and sculptures inspired by the eponymous erotic novel of 1828 by John Benjamin Brookes. Possibly as a tool to fortify the exoticism of the setting, Brooke’s prose was characterized by a rather liberal and evocative use of soft furnishing elements like cushions, tassels, tiebacks, and curtains—a fact that Di Massimo quickly noticed and incorporated into his work in the form of objects substituting body parts. Such a strategy, coupled with a visual style ostensibly indebted to the Mediterranean tradition, gives The Lustful Turk works close links with the paintings of Di Massimo’s heroes Dalí and de Chirico.

The representation of a pile of black cushions with human limbs (a concept that Di Massimo later enacted in a performative piece titled Inside Me, 2013) particularly stands out as a fitting example of how this morphological process can generate new organisms within the limits of a vocabulary exclusively made of mundane and familiar objects. The influence of Surrealism is also visible in his portraits, where scenarios and characters are incongruously matched so as to challenge their realism. As Di Massimo himself is fond of reminding us, portraiture is the genre that persistently interrogates human nature, and it is this ingredient that manages to give an edge to his work even in his most conservative moments.

– Michele Robecchi

[related-works-module]