The first 16 years of the new millennium have witnessed a veritable flowering in contemporary art, with widely diffuse approaches and media proliferating throughout all areas of artistic endeavor as artists struggle to make sense of a shifting yet increasingly interconnected art world. For Part 1 of our list of must-know recent sculpture, we’ve excerpted 10 notable works from Phaidon’sThe Twenty-First Century Art Book that illustrate the diverse and innovative ways in which these artists have responded to our century thus far.

MARCELO CIDADE

Imóvel, 2004

Sixty-one concrete breezeblocks have been neatly stacked up in a supermarket trolley. As well as borrowing from the language of Minimalism, the sculpture evokes the Modernist tower blocks in the artist’s home city of São Paulo. As the work’s title suggests, the trolley has been rendered useless, made immobile (imóvel) by the sheer weight bearing down on it. Concrete is a recurring material in the young Brazilian artist’s work, alluding to the wave of utopian Modernist architecture that promised to transform so many Latin American cities, yet arguably failed to deliver. The urban environment is a central concern for Cidade, whose works engage with language, politics, and art history. His sculptures, installations, films, and actions explore the Post-Modern condition of the city and the relationship between public and private space. While Cidade’s studio pieces often incorporate urban elements, the former graffiti artist also performs subtle and anonymous interventions in the streets themselves.

ANDREAS SLOMINSKI

Monkey Trap, 2004

Slominski’s ongoing series of traps are set not for animals and birds – although, if triggered, they would reportedly function efficiently—but for the eyes and minds of humans. While sculptures such as Monkey Trap are metaphors for the way an artist ensnares a viewer’s intellectual curiosity, they are also traps in the sense that they lure viewers into constructing interpretations, then snap shut—claiming only to be traps after all. Monkey Trap purportedly relies on the monkey’s greed, which keeps him grasping a banana even though it is too large to extract from the cage. Can this be a genuine method for catching monkeys or is it a shaggy dog story—another kind of trap for the gullible? In works such as Imprint of the Nose Cone of a Glider (2005), nothing more than a dented panel of foam, viewers once again have only Slominski’s mischievous word to rely on.

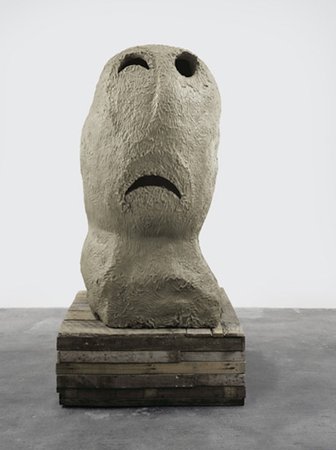

UGO RONDINONE

MOONRISE. east. april, 2006

Rondinone is an artist more easily identifiable through his sensibility – gently humorous, melancholic, and attuned to quiet moments of surprise and delight in daily life – than he is by his diverse subject matter. Over his career spanning two decades, the New York-based artist has made airbrushed, circular paintings resembling targets, jolly rainbow-patterned signs with messages such as Hell Yes! (2001) and, more recently, giant statues made from roughly hewn lumps of rock, installed in New York’s Rockefeller Plaza (Human Nature, 2012). MOONRISE. east. april belongs to a twelve-part series of clay heads, each titled after a different month of the year. The initial sculptures were made in clay; the artist’s finger marks are preserved in the final bronze casts, which were painted to resemble their original material. Sculpting these monstrous though friendly faces, Rondinone meditates on the passage of time and the importance of daydreaming and fantasy.

ISA GENZKEN

Hospital (Ground Zero), 2008

An assemblage of disparate objects has been arranged and shrouded in fabric to suggest the outline of a skyscraper. This is one of a series of architectural proposals that the artist made for the former site of the World Trade Center in New York. The appearance is haphazard and precarious. However, Genzken worked with a team of structural engineers to ensure that they could be built to the scale of the Twin Towers. Genzken cannot be defined by a single medium or tradition, but she has developed a distinctive aesthetic and uses recurring motifs. The column, for instance, is employed to explore the relationships between art, architecture, design, and social experience. Her work contains a flamboyant sense of humor. She creates monuments and structures that explore notions of both construction and deconstruction through a light-hearted perspective. Hospital (Ground Zero) commemorates a destructive historical event, yet builds a colorful, optimistic, and humane tribute.

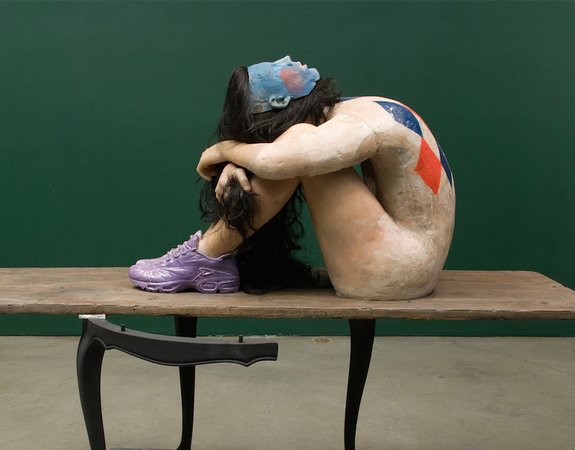

ANDRO WEKUA

Sneakers 1, 2008

A spookily life-like wax figure of a dark-haired girl sits hunched, with her head buried in her knees. On her back is painted a harlequin pattern and on the crown of her head a theatrical mask smiles at the ceiling. But for a pair of purple sneakers, she is naked. She is placed on top of a makeshift table assembled from diverse parts, which stands on a pallet cast from aluminum. The pallet and table provide a functional plinth but their presence is so particular that they also serve as a device to further focus attention on the figure. Part of a series of cast-wax mannequins, in which the same sneakers play a recurring role, Wekua has staged an image of childhood solitude and indeed loneliness. In his sculpture, paintings, and photography he draws on personal and shared iconographies to develop narratives through which he explores human experience at the intersections of individual and collective memory, identity, and history.

[related-works-module]

TONY CRAGG

Lost in Thought, 2011

This towering sculpture is made from hundreds of layers of laminated plywood. Its twisting curves and recesses allow viewers to see inside and right through the complex structure. Adopting an intuitive approach, Cragg let the work take shape organically, building it up layer by layer from the inside to the outside. For the artist, it relates to the idea of being lost in one’s thoughts and the social defenses that we erect to protect ourselves. Cragg emerged in the 1980s as a key figure of the New British Sculpture movement, a group of sculptors whose production of objects marked a departure from the conceptual practices that had characterized the preceding decade. Drawing on his early training as a scientist, Cragg constantly experiments with new materials, styles, and techniques. Working with bronze, glass, plaster, steel, wood, clay, plastics, as well as found objects, he continues to explore and expand the language of sculpture.

JOANA VASCONCELOS

Lilicoptère, 2012

For this sculpture, Vasconcelos adorned a Bell 47 helicopter with ostrich feathers and thousands of rhinestones. Its lavish interior is further bedecked with intricate woodwork, sumptuous gilding, and embroidered upholstery. Inspired by the opulent surroundings of the Palace of Versailles, France, where it was first exhibited, Vasconcelos’s work draws on the grand aesthetics of the Ancien Régime, speculating the type of motorized vehicle that Marie Antoinette might enjoy were she alive today. Such extravagant and witty projects are typical of the Lisbon-based artist, who de-contextualizes and subverts commonplace objects, investing them with new meanings. By delving into the past, Vasconcelos offers a critique of the present, exploring themes of gender, class, and identity. Much of her work addresses feminist issues and often employs artisanal techniques and craft-related materials associated with female labor. Vasconcelos first attracted international attention at the 2005 Venice Biennale when she exhibited a giant chandelier made of tampons.

NICHOLAS HLOBO

Ndize: Tail, 2012

Working with materials as varied as leather, lace, satin, and the rubber inner tubes of car tires, South African artist Hlobo creates large-scale installations, as well as paintings, drawings and performance-based works. Ndize: Tail is displayed across the walls and floor of the gallery space, and the mix of brightly colored ribbons, leather, and rubber come together to form a design that is abstract yet suggestive of something organic, perhaps the remains of an enormous multicolored beast. The items that Hlobo uses have multiple references, to Xhosa culture as well as urban life in Johannesburg. Their meaning in his work is ambiguous: Hlobo’s use of leather, for example, refers to the importance of cattle for the Xhosa people, although is also used by the artist to create sexualized imagery, including allusions to fetish gear. Hlobo also makes reference to gender, deliberately mixing materials regarded traditionally as masculine and feminine.

YTO BARRADA

Twin Palm Island, 2012

Yto Barrada’s hometown of Tangier provides the socio-political backdrop for her manifold activities as an artist and an activist. Just 8 miles from Europe, the city is both a jumping off place for the hopes of African migrants, and a crossroads of civilizations. Barrada’s early work as a photographer offered quietly haunting images of the landscapes and people of Tangier, and often relied on implied absences: a book of her photographs published in 2005 was titled A Life Full of Holes. Her 2012 touring exhibition “Riffs” and 2013 monograph expanded the scope of her inquiry beyond the city to the surrounding “third landscape” at the edges. The toy-like fairground signage of Twin Palm Island is part of the artist’s critical assessment of uses of the botanical in Moroccan public space, including photographs, films, sculptures, and posters featuring the polyvalent symbol of the palm tree.

SARAH LUCAS

Patrick More, 2013

Lucas emerged in the early 1990s as a leading member of the Young British Artists, the irreverent and ambitious group whose affinity for working-class vernacular culture and post-Thatcher DIY resourcefulness lent them swift and widespread acclaim. In 1993 Lucas opened a shop with Tracey Emin, which sold handmade knick-knacks and closed after six months. Lucas’s “Bunny” series, begun in 1997, was based on figurative sculptures made from tights stuffed with cotton wool. The tights became lumpy, sprawling legs, which Lucas often fixed to chairs, as if they were sitting. These works led to another series, “NUDS” (2009), in which she knotted stuffed tights into abstract (though corporeally suggestive) objects that sit on breezeblock pedestals. In more recent pieces, among them Patrick More, Lucas casts the soft sculptures in polished bronze, explicitly acknowledging the influence of mid-century Modernist sculptors such as Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth who have long shadowed Lucas’s work.

[related-works-module]