Writing about his teenage years in his classic autobiographical novel cycle In Search of Lost Time (1913-27), Marcel Proust observed that “the salient feature of the absurd age I was at – an age which for all its alleged awkwardness, is prodigiously rich – is that reason is not its guide. There is scarcely a single one of our acts from that time which we would not prefer to abolish later on. But all we should lament is the loss of the spontaneity that urged them upon us. In later life, we see things with a more practical eye, one we share with the rest of society; but adolescence was the only time when we ever learned anything.”

Reading these words, anybody who has climbed beyond the foothills of their early twenties will recognize that Proust was correct. Our teenage years are a formative maelstrom of hormones and feelings, experimentation and individuation, a period of awakening when we receive lessons, both personal and political, that we’ll carry with us for the rest of our days. This is a time that we look back on with both nostalgia and regret (as the playwright George Bernard Shaw put it, “Youth is wasted on the young”) tempered by an astonishment at the strange appetites and motivations of our own past selves (in the words of Shakespeare “A man loves meat in his youth that he cannot endure in his age”).

It is teenagers’ combination of physical beauty and emotional ardor that has made them a perennially popular subject for great artists. Think of Edgar Degas’ canvas Young Spartans Exercising (1860), or Diane Arbus ’s photograph Teenager with a Baseball Bat , NYC (1962), or Elizabeth Peyton ’s recent, breathtaking portrait painting Greta Thunberg (2019), in which the adolescent environmental activist stares out of the image with glacial blue eyes, challenging the past and facing up to a dark future.

Here, we showcase six works by contemporary artists that smell like teen spirit. Engaging with youth’s playfulness and turbulence, its earnestness and caprice, they are testament to the brief years during which we shine like newly made stars, even when we are deep in the shadow of adolescent angst.

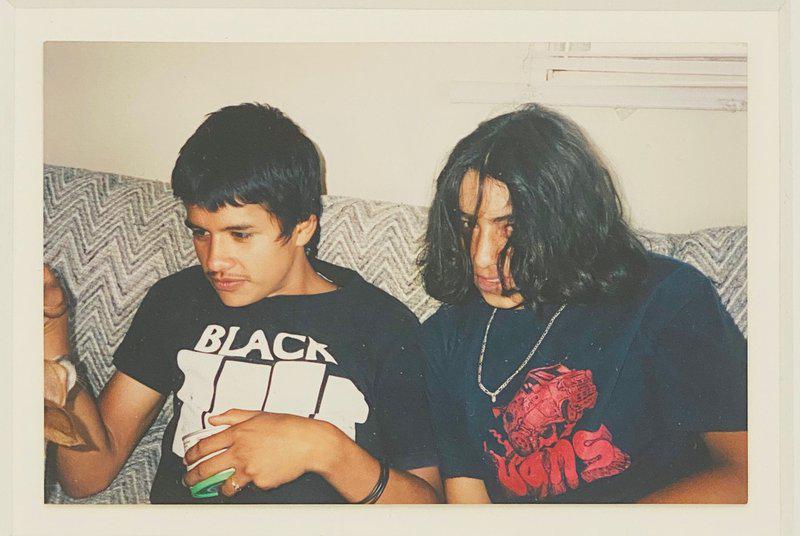

Larry Clark - Unique Color Photo (FUJI Film)

The cultural figure of the teenager is to a large degree a postwar American invention, and it follows that many of the great chronicles of adolescent life hail from the US: J.D. Salinger’s novel The Catcher in the Ry e (1951) and Sylvia Plath’s roman à clef The Bell Jar (1963), Nicholas Ray’s movie Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and Sophia Coppola’s film The Virgin Suicide s (1999). To this canon we should add Larry Clark ’s landmark book of photographs Tulsa (1973), an extraordinary, unflinching series of grainy black and white images shot in the artist’s Oklahoma hometown, which depict local youths caught up in a nihilistic whirl of sex, drugs and violence, as though tomorrow – or at least adulthood – will never arrive.

In this later work, Clark once again takes teenagers as his subject. The two boys in this shot are not, we should note, the kind of perky, preppy, flawlessly beautiful “adolescents” who populate American TV shows such as Dawson’s Creek and Beverly Hills 90210 (who are in any event usually played by actors in their 20s). Rather, with their buff-fluff moustaches, awkward postures and greasy, grown-out hair, these kids are the real pubescent deal. Slouching on their mom’s couch, wearing t-shirts that pledge allegiance to skateboarding culture and the punk rock group Black Flag (sample lyric: “I see my place in American waste / Faced with choices I can’t take”), they grow slowly and gracelessly towards an uncertain future.

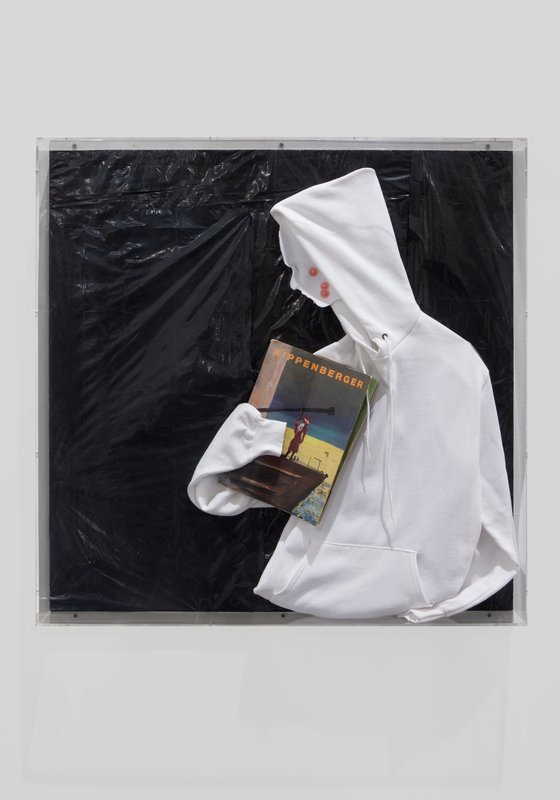

Keith Farquhar - Teenager (Kippenberger) (2007)

In 1979, the legendary German artist Martin Kippenberger became the manager of the Berlin punk club SO36, attracting such luminaries of experimental music as Throbbing Gristle and the pioneering synth duo Suicide. However, a hike in beer prices and Kippenberger’s trollish, more-punk-than-punk preference for wearing business suits to work so upset some of the club’s young patrons that a group of them – led by a woman named Ratten Jenny, so-called because of the pet rat that perched perennially on her shoulder – assaulted the artist one night, leaving him with a broken nose and numerous facial scars. Not letting this unpleasant experience go to waste, Kippenberger had his friend Jutta Henglein photograph his bruised and bandaged face, an image which he transformed into a painted self-portrait, bearing the droll title Dialogue with the Youth (1981).

This art historical anecdote provides the backstory for the acclaimed Scottish artist Keith Farquhar ’s sculpture Teenager (Kippenberger). Here, we’re presented not with a Berlin punk, but a British hoodie – a member of a 21st-century adolescent tribe that faces much the same tabloid demonization as their spiky-haired forebears did in the far-off 1970s. Today, now that a number of former teenage punks are now grown-ups employed in powerful media roles – and have long swapped sniffin’ glue at the 100 Club for sippin’ barolo at the River Café – the subculture they once belonged to is presented as the subject of affectionate nostalgia, rather than as a cause of anxiety. Might the figure of the hoodie be one day similarly embraced? After all, with his pristine white sportswear, Farquhar’s spotty adolescent is hardly the stuff of adult nightmares. Look: he’s even clutching a coffee table book about Martin Kippenberger, the unforgivably well-tailored supposed nemesis of youth.

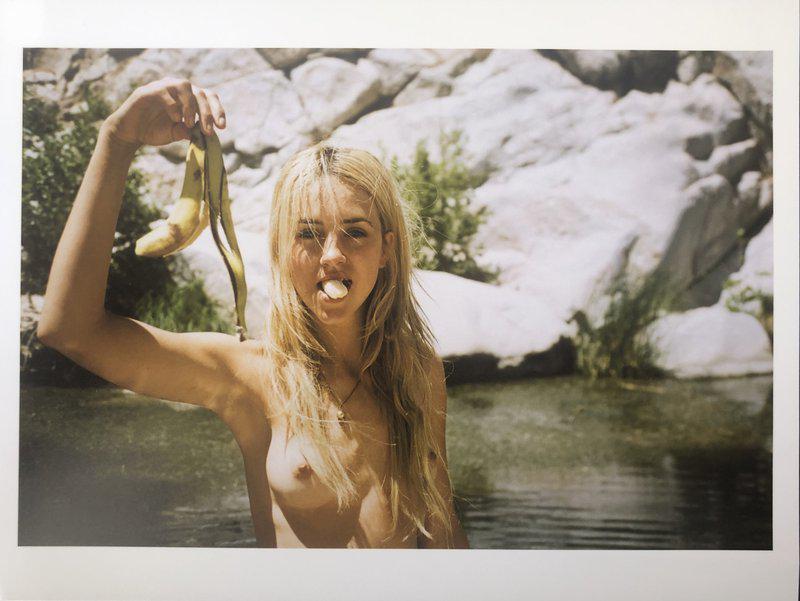

Magdalena Wosinska - Banana (2016)

Born in Poland in 1983, the emerging photographer Magdalena Wosinska moved to the US in 1991, spending her teenage years involved in Arizona’s skate and metal music scenes. Now based in LA, Wosinska’s rawly spontaneous work – which is always shot using ambient light – captures the energy, impulsiveness and carefree beauty of her youthful subjects. Suffused with an atmosphere of endless, heat-hazed summer, these are images in which the world feels full of possibilities, and in which the grown-up stuff of disappointment, compromise, and responsibility is kept forever at bay.

Wosinska’s photograph Banana depicts a blonde-haired, bare-chested young woman standing in (or perhaps beside) a rocky, sun-strafed swimming spot, a pearl pendant around her bronzed neck, a chunk of yellow banana clamped between her teeth. In her right hand, she holds up the fruit’s lolling, empty skin like an angler who’s just landed a prize fish, although the expression in her eyes – a kind of mocking sultriness – seems to indicate that her real “catch” is the male viewer, or more precisely the banana-like organ between his legs. If she is, to a degree, a 21st century take on the sirens of Homer’s Odyssey – whose sweet music lured lonely sailors to wreck their ships on the sharp rocks of these creature’s island home – then this is a role she plays for laughs. Youthful beauty is fleeting, so why not use it to make a knowingly dumb castration gag while the summer sun still shines?

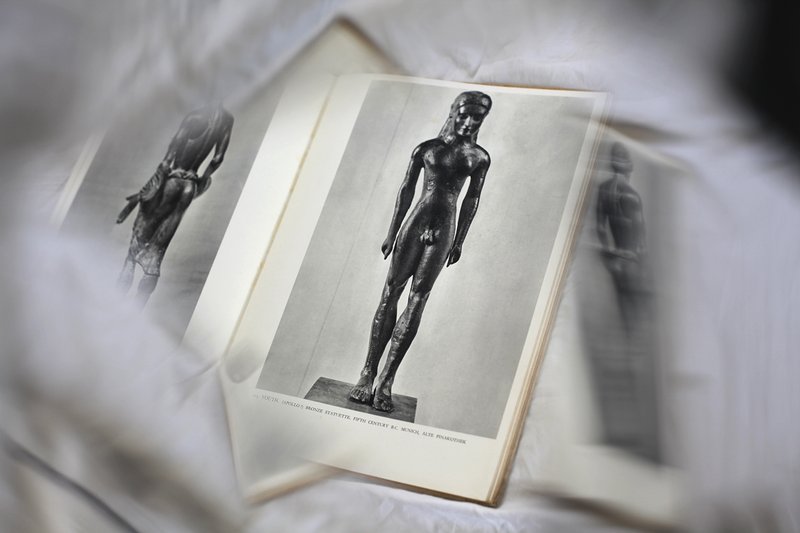

Rami Maymon - Untitled (Youth) (2013)

Kouri are sculptures of naked young men, which first emerged in early Greek antiquity. With their long hair, beardless features and left legs striding confidently forward as though into a bright new day, these figures are thought by some archaeologists to be representations of the god Apollo, and have been found at numerous sites sacred to this youthful – and famously comely – deity. Other scholars have identified kouri as depictions of the erômenos (or younger partner) in homosexual relationships between teenagers and adult males, while a third theory sees these sculptures as embodiments of the Archaic Greek notion of arete, an aristocratic ideal combining physical and moral beauty. As the 6th century BC poet Simonides described it: “In hand and foot and mind alike foursquare / fashioned without flaw”.

In this photograph by the noted Israeli artist Rami Maymon , we see a book open on a black and white image of a bronze kouros, from the collection of Munich’s Alte Pinakothek, against a backdrop of what appear to be white bed sheets. On the left-facing page we glimpse the pert buttocks of another sculpture, shrouded in tight fabric, which are repeated, in a blurred reversal, on the right of Maymon’s shot. The impression is of an unseen reader flicking through a museum catalogue, as they while away a lazy, languorous hour in bed. Is this book a source of cultural edification, or a notably highbrow masturbatory aid? Forget the repressive – and often hypocritical – Christian morality that replaced the Classical world’s sexual candor, and there’s no reason it can’t be both.

Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen - Young Couple, Byker (1975)

Byker is a working-class neighborhood in Newcastle upon Tyne, North East England, famous for Ralph Erskine’s landmark postmodernist public housing project Byker Wall, which was built between 1969 and 1982 to replace the area’s moldering Victorian slums. In the period leading up to Byker Wall’s completion, the Finnish photographer Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen spent seven years living in this community, documenting the lives of its members in a series of black and white photographs that have been widely praised for their powerful sense of social engagement. As Konttinen has said of her project: “Being a foreigner gave me one advantage: I could be nosy, and be forgiven. Many doors were opened to me that would have remained closed to another photographer”.

Few images in this body of work are as intimate – and as disquieting – as Young Couple, Byker. In this shot, we see a man and woman, barely out of their teens, in the backyard of a terrace house. He is naked, his hair curling wetly at his nape, as though he’s just drenched his head in a sobering bucket of cold water. Clothed in a dark dress, she grasps her lover’s hand, and utters a silent plea, appearing to talk him down from some unknown (self?) destructive act. To the left of the image a little boy stares at the ground, wishing away the tense scene that plays out beside him. Above his head hangs a dartboard, which seems to mark him out as a target for sudden, sharp violence. Is he the couple’s child? If so, what parental example might they set him, when they are little more than children themselves?

Collier Schorr, Young Rider (2008)

Adolescence is a time in life when many of us cycle through identities. Visit a teenage nephew at Christmas, and he might be a kohl-eyed, Doc Marten-shod emo. Return at Easter, and chances are he’ll have exchanged these dark and moody signifiers for the Supreme streetwear and box-fresh Yeezies of the high school hypebeast. What, though, of youths who grow up in communities in which identities are much harder to shrug on and off, such as the pubescent cowboy in

Collier Schorr

’s photograph Young Rider? What’s at stake for him is the continuation not only of a sartorial tradition, but of a whole mythology. The cowboy, after all, is the embodiment of American masculinity, a knight errant in a Stetson, a John Wayne-sized pair of (spurred) boots to fill.

Adolescence is a time in life when many of us cycle through identities. Visit a teenage nephew at Christmas, and he might be a kohl-eyed, Doc Marten-shod emo. Return at Easter, and chances are he’ll have exchanged these dark and moody signifiers for the Supreme streetwear and box-fresh Yeezies of the high school hypebeast. What, though, of youths who grow up in communities in which identities are much harder to shrug on and off, such as the pubescent cowboy in

Collier Schorr

’s photograph Young Rider? What’s at stake for him is the continuation not only of a sartorial tradition, but of a whole mythology. The cowboy, after all, is the embodiment of American masculinity, a knight errant in a Stetson, a John Wayne-sized pair of (spurred) boots to fill.

Is Schorr’s young gaucho ready to step up? Tellingly, she pictures him not in action at a rodeo or line dance, but sitting on a folding chair, waiting for something (adulthood, perhaps) to begin. A fresh crease ironed into his jeans, his new checked shirt spotlessly clean, his clothing is as unmarked as his baby-smooth cheeks. What experiences await him? Here in the 21st-century, probably nothing that would compare to the tough, violent life of a Jesse James or Billy the Kid. Still, this soft-faced youth will soon be hardened by the macho ideal he is expected to live up to, which has been passed down through the generations. Will this prove to be a golden legacy, or an ancestral curse?

[ahyouth-module]