In Artspace Magazine 's series Art in the '90s , we look at the most pivotal works from a decade that is not only having a comeback in contemporary culture, but that paved the way for many multimedia, video, and social practice artists working today. Excerpted from Phaidon's Defining Contemporary Art––25 Years in 200 Pivotal Artworks , the following text written by super-curator Hans Ulrich Obrist discusses the most pivotal work of 1990: Damien Hirst 's A Thousand Years .

Damien Hirst once recounted to me the story of the time he received a telephone call from an art gallery to inform him that Francis Bacon —one of the artist’s great heroes—had been standing, captivated, in front of the same Hirst piece for an hour. The work in question was A Thousand Years , first exhibited at the pivotal YBA exhibition, “Gambler,” curated by Carl Freedman and Billee Sellman at Building One, a former warehouse in Bermondsey, London, in 1990.

It is in A Thousands Years— and in the later, now iconic The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991)—that so many of Hirst’s themes and influences are most clearly revealed and most thoroughly worked through. As he has said, “There has only ever been one idea, and it’s the fear of death; art is about the fear of death.”

Damien Hirst, "A Thousand Years" (1990). Image courtesy of the artist and Science Ltd. Photo: Roger Wooldridge.

Damien Hirst, "A Thousand Years" (1990). Image courtesy of the artist and Science Ltd. Photo: Roger Wooldridge.

A Thousand Years takes the shape of a rectangular glass vitrine, bisected at the midway point with a glass sheet that has been pierced with a few round holes. In one half of the vitrine is a severed cow’s head, with an insect-electrocuting light suspended above it, while the other half contains a large white die, with one dot on every face. (You can’t win.) Maggots released into the cage-like container feed on the cow’s head and metamorphose into flies before inevitably ending their lives on the electrocuting light. Hours can be spent observing the flies going about their business with what appears to be the utmost freedom, but which is in fact a freedom totally constrained by an inevitable ending zap. This curtailing of freedom by fate is a little like John Cage’s notion of controlled change.

Hirst relinquishes control of these creatures to a certain degree of freedom or chance but then has the last laugh: “The fear of death is the strongest emotion, so as an artist when you start thinking about these things you end up thinking about that kind of darkness. […] It’s about how you can cushion yourself from death in some way.”

Besides Hirst’s abiding obsession with the passage from birth to death, and with the enshrouding of all human and animal activity in a final, blunt futility, the work sets in motion the artist’s now familiar deployment of minimalist forms— Donald Judd , Sol LeWitt , Bruce Nauman , Dan Flavin , and Dan Graham all make an entrance here—charging their quiet repose with a strong sense of existential fear and foreboding. The vitrine, in this instance, is large enough for us to easily imagine our own imprisonment within its seven glass walls. A Thousand Years makes plain—before the famous shark, that oversized fish in an undersized aquarium—Hirst’s ongoing fascination with containment and the crucial difference between being caught inside and looking in from the outside.

Glass, and its perceptual tricks, exert a particular hold on the artist: “I’ve always had a thing about glass. I had a magic mushroom experience very early on where I got a bit freaked out about being symmetrical. I imagined I had a sheet of glass running right through me. Glass became quite frightening. I think glass is quite a frightening substance. I always try and use it. I love going round aquariums, where you get a jumping refraction so that the things inside the tank move; glass becomes something that holds you back and lets you in at the same time. It’s an amazing material; it’s something solid yet ephemeral. It’s dangerous as well.” A Thousand Years, too, is dangerous and frightening, and these qualities were crucial to its influence on the trajectory of art during the 1990s. As Hirst concludes, “Frightening things attract us.”

[related-works-module]

RELATED ARTICLE:

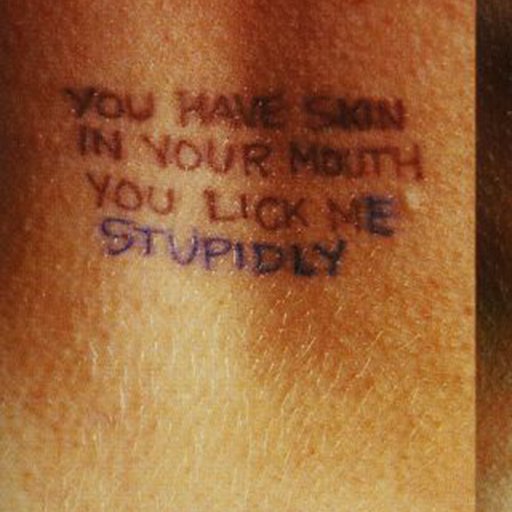

1993: Jenny Holzer's Feminist "Sex Murder" Raised Fury in Germany—For All the Wrong Reasons