If the New York art world is a kind of royal court populated by empurpled dealers, landed collectors, waggish artists, and all manner of opulently bourgeois courtiers, then Walter Robinson is the kingdom’s scribe—and also, from time to time, its jester. The critic and founding editor-in-chief of Artnetmagazine for 16 years, he has chronicled the “radical masquerade” of the avant-garde, heralding new talent, skewering the deserving, and identifying epochal shifts in the art scene, from his pronouncement that "there are no art movements, only market movements" to his lament about the rise of “zombie formalism” in contemporary painting today. (The latter in his column on Artspace, "See Here.")

Robinson is also, with equal emphasis, an artist in his own right. Having emerged in the 1980s East Village along with Richard Prince and Sherrie Levineas part of the Pictures Generation, he playfully appropriates mass-media images from pulp book covers (in his "Romance" series) to JCPenney ads and also paints objects of lust and desire, from the scantily clad selfies escorts use to promote themselves in Backpage magazine to Pop portraits of decadent cheeseburgers and whiskey bottles. A graduate of the elite Whitney Independent Study Program in the early '70s, Robinson was also a member of the influential artist co-operative Colab, together with Kiki Smith, Jenny Holzer, John Ahearn, Tom Otterness, and other artists.

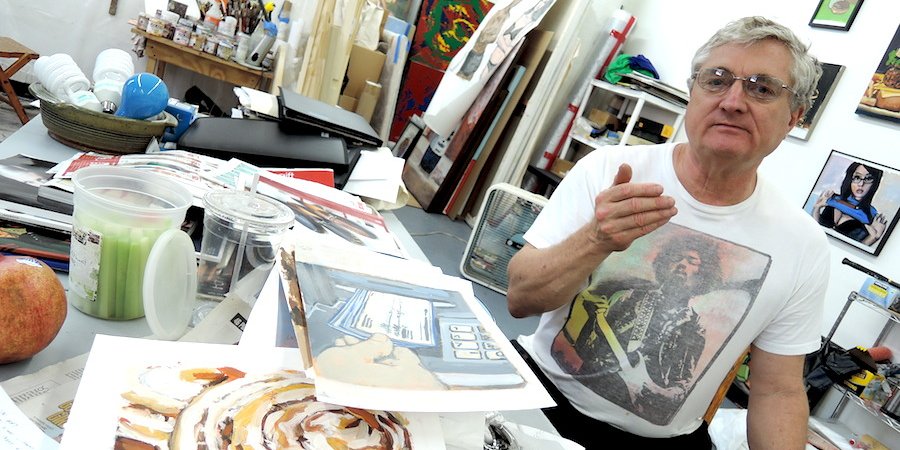

This month, Robinson has a new show at Lynch Tham gallery in New York (up until July 17), featuring paintings of the glossy pages of department-store catalogues, lightly marbled with art-historical jokes. Artspace's Noelle Bodick visited the artist-critic at his Long Island City studio to sit down with a container of celery and a bowl of hard sugar-free candies and talk about indulgence and desire in American society, and how these ideas play out across his canvases. (Interspersed throughout the interview are photos of work in progress at Robinson's studio.)

RELATED LINKS:

The Pen Is Mightier Than the Brush? Looking at 6 Famous Artist-Critics

What was the genesis of the latest body of work? Why department store flyers and ads?

It seemed like a funny idea at the time. That kind of imagery is so ordinary, so unremarkable, it's everywhere—the exact opposite of the avant-garde. At the same time, like the avant-garde, it's an idiom all its own, with it's own unique characteristics that are historical and transitory. Do you know the pulp images I exhibited back in the ’80s? They came from what I thought was a lost or discarded image bank, and this kind of low-end fashion stuff is a similar subject, a "collection" that is baroque but boring. It's kin, I guess, to that classic advertising genre—bra ads.

Like any healthy American teenage boy, I was always interested in bra ads. But you know it's funny, those ads aren't really aimed at boys, they're aimed at women, though of course they’re aiming at men via women, or at women via a projection of a male gaze. Once you start examining department-store fashion ads, it's clear they segment their audience in this and other ways, and that dynamic is peculiarly alive, in a way many pictures are not.

You're interested in a particularly middlebrow form of fashion: Macy’s, JCPenny, Target, L.L. Bean, and Lands’ End.

It just comes to you, in newspaper flyers or via email, or in ads and posters. It's like air or sunshine. I try to avoid using Bergdorf’s. It’s got too much "fashion" in it. And J.Crew is too metrosexual. What I want is norm-core! I want it to be plain. One of the first ones I used showed three women modeling pajamas, joyful but demure, like a middle-class "Three Muses." I liked that it had the faintest ghost of a classical motif, that its sexual allure was so surreptitious. And I was especially into the idea that the images are actually selling to the viewer—they involve the viewer in a kind of feedback loop. A regular painting just sits there on the wall, and you look at it. These beckon you. They’re smiling at you. They're selling pajamas.

Among the paintings at Lynch Tham is a row of neatly folded plaid Lands’ End shirts, playfully alluding to the geometric blocks in an Ellsworth Kelly painting. In another painting, a pair of red rain boots ($25 dollars, the title tells us) pay homage to van Gogh’s hobnailed boots, written about in German philosopher Martin Heidegger’s famous essay on aesthetics. What got you thinking about these delightful meetings between art history and fashion catalogues?

It’s an additional reason to paint something, if it makes a reference. Ross Bleckner's show a couple of months ago at Mary Boone gave me the idea about stripes and dots, which just happened to match up with the new Lands' End designs for women's beach wear this summer—it's all striped. After I painted some of these models, I started noticing people wearing stripes all over the place. It would be good, I thought, if whenever you saw a person in a striped shirt or dress, you'd think of me. Or a plaid shirt. It's the essence of capitalism. Take something that belongs to everybody and claim it as your private property.

So dispense with originality and take from a catchall of references and styles?

In the old days, before say 1980, the view was you couldn't do anything anyone else had done. You had to be original. But now everything has been done! So you can either try harder and harder to do something new, or give it up and make things that are obviously copies. Instead of being grandiose and situating yourself above everyone else, which is ridiculous anyway, you're taking a place in the middle of a network of references. It's realer, and more fun.

With this body of work, you aren’t fretting over the gaping maws of consumerism or something punishingly serious like that?

No, this is consumerist utopia! Everybody’s happy. It’s a perfect world. I've become utterly absorbed by the capitalist ideal. If there’s anything I hate, its all the hall monitors that have taken over the art world. They're bureaucrats. All they want to do is enforce their petty rules. It happens most in discussions of race and gender, but let me give you a less sensitive example: [former Guggenheim director] Tom Krens putting motorcycles on the ramp of the Guggenheim Museum. You'd have thought he was betraying the museum's core values, but it was just dumb. And now it's forgotten. What I’m saying is that so much art today is grasping after its "superiority complex." That's where it finds its value, its excuse for being, and so it strains to be “good for you”—an idea that is very American and very Puritan—whereas I'm holding out for the primacy of play.

So you playfully employ the strategies of corporate America, appealing to our impulse to… buy?

You make it sound so delightfully abject. I definitely want to piggyback on that desire dynamic that is already built into consumer products. I like that. People want Dristan when they have nasal congestion. And, look, the company has already designed the package to be perfectly appealing. I want my paintings to have that same appeal. It should be irresistible. Something must be off though, since nobody bought that still life of a Dristan spray bottle. Maybe I should have put in an apple.

Do you blame corporate strategy for your unsold paintings as well then?

In 1985, I sold a painting of Johnson & Johnson baby oil to Johnson & Johnson. It worked perfectly. I also once made a painting of a bottle of frozen lemonade. It was just like a still life. I had this collector, a friend of mine, and looking at it, and he was getting interested, so I said, “Yeah, I painted that because I wish women’s pee tasted like lemonade. That’s why I painted that.” It was supposed to have a secret sexual meaning. And of course, he turned away immediately and left without buying it, because who wants to have a painting that when you look at it reminds you of women peeing and what it tastes like? Nobody wants that.

Is it better to play mute as an artist?

My advice would be to keep your mouth shut. Still waters run deep.

You were the editor-in-chief of Artnet magazine for 16 years and are an Artspace columnist. What’s the difference for you between painting and writing about art?

It's fundamental! A critic talks about everything and anything, but an artist can talk only about one thing: him- or herself. A critic, especially one who works for a website that posts daily, can have their say every single day. Most artists work alone in their studios and are able to show their art infrequently, maybe once or twice a year.

How does being an artist shape your criticism?

I suppose you could say because I’m an artist I have a particular angle on art: how it’s made, how the artist works. I look at it less in the abstract. I’m also much more interested in the market angle of things than a lot of critics.

You have a record of hailing the market as a powerful marker of value and useful benchmark. How does that thinking affect your work as an artist?

The art market talks to me. I only just realized that the other day. It tells me everything. My problem is that I'm too neurotic to listen, at least much of the time. I need an art-world Cesar Millan. A Market Whisperer. That's what the art flippers have... isn't it?

Since the 1980s art-market bubble burst, however, figurative painting has not been particularly fashionable in the market.

I can only do what I can do. It’s funny that art is supposed to be about freedom, but artists typically have been locked into their individual brand. I think it's loosened up some in the postmodern era. You see a lot of artists working across disciplines in the 20-something art world. It's like a new planet, this 20-something art world.

You've said that as a figurative painter, the toughest part is finding a subject.

It’s not the picking, it’s the justifying. For me it was always about desire. A lot of the things I was reproducing are charged with sexuality. They are romantic—it’s like being a troubadour, seducing people, unleashing the libido. Painting pictures of people are like passionate embraces. Back in 1985, Kim Levin did a tiny Village Voice pick review of the spin painting show I had at Metro Pictures. She said they gave “a frisson,” a shiver. I didn't like it then, but at least it was in French. All of this stuff is about desire.

Do you paint things you can’t have?

I deny myself nothing. I’m a child of the ’60s. Or I did. Now it's all a vivid memory.

Do you want to unveil the mechanisms of desire?

Oh, no. I'm not on any kind of mission. I'm no Carrie Nation.

Is there any particular kind of art you don’t like?

Yeah, plenty. I hated the idea that Tino Sehgal would hire kids to interrogate visitors at the Guggenheim, for instance. Like that mope has anything profound to teach us. But what are you going to do? First rule of the art world is "don't fight success." Rejecting hip art is reactionary, it's the avant-garde's own Catch-22.

In a recent Artspace column, you said artists are like mutants, like in X-Men with unique superpowers. Which mutant would you be?

Oh, that's a good question. What about Mystique? She’s always disguising her superpowers in a norm-core shell. And she's played by Jennifer Lawrence—what guy wouldn't want some of that?

You know in the new X-Men movie, the bad guy steals Mystique's shape-shifting powers and creates these giant robot Sentinels that can absorb any mutant power and ultimately destroy the X-Men altogether. The Sentinels are like capitalism, which has the supreme power to take any radical art and domesticate it for popular consumption.

So, resistance is futile?

Artists just play. And I actually like consumerism. When people complain, “Oh god, the world is going to turn into this big consumerist thing where there’s nothing authentic.” And I really don't understand what they're worried about. Everybody loves shopping. I remember when I first felt it back in the ’80s, living in a crummy apartment on Ludlow Street, so depressed I didn't know what to do. I didn't have any motivation. But then, I’d think, “I know, I’ll go to the hardware store and buy some stuff. Then I’ll feel better.”

You don't seem to have gone into a profession that is profitable enough to allow much shopping.

I know! Like I didn't know what I wanted to do. I liked art, so I should have gone to business school. My father wanted me to go into the oil business. Instead I went into the acrylic business, which is very much like “The Graduate.” “I got one word for you son, plastics.” See, I watched “The Graduate” and I was like, “Oh, okay plastic paint.” Sorry, what was the question? I am the king of tangents.

A signal of originality. But you don’t want to be original.

I want to be as unoriginal as possible.

Can think of your paintings of Target bathing suits or Lands' End rain boots as another commercial advertisement?

That’s just an idea, a bit of narrative. I don’t know what's really happening, what the actual effects are. That’s why we all hate the culture industry so much, because it steals all our impulses and desires. We have these inchoate emotions that demand satisfaction, and capital gives them a form and sells it to us. They steal singing around the campfire and turn it into copyrighted top-50 hits that we all follow slavishly. Kids love Mickey Mouse, but Mickey doesn't belong to them, he belongs to the Disney Corporation. The culture industry has stolen imagination. They've stolen people’s imaginations.

So why appropriate?

I have a list of reasons on my iPhone, here, I'll read them to you:

1. It’s an admission of defeat.

2. The artist quails in the face of the spectacular.

3. It’s a transformation of the ordinary into the sublime.

4. These catalogues want to be art and I’m helping.

5. You don’t have to worry about being aesthetic. (I’m not going to devote myself to cultivating some kind of discrimination. That’s ridiculous!)

6. Reanimation: it’s old, dead, out of print, only available in archives.

7. Because it’s not allowed. (This is the Richard Prince thing, the thrill of transgression.)

8. You know what’s going to happen (In real life you know what’s going to happen too, it’s going to be bad. But in the movie it’s going to be good. The hero is going to win, unless it’s a Cormac McCarthy book and then the bad guys win! I hate that.)

9. To be fake.

10. To be already existing rather than invented.

Yeah, I wonder if I’ll be sued.

Other than a possible lawsuit, what’s next for you? Do you think you’ll keep with the catalogs?

I don’t know, maybe I’ll give the whole thing up. I want to be like John Singer Sargent. He was a society guy and he’d go to some dinner or something and they'd all be talking and after a while he’d get so bored and say, “Do you have any paints?” And then he’d just make a painting. I want to do that.

So ignore the lousy company and devote yourself to your oils?

If I could paint like Sargent, that would be good and I could do that. When artists get in their groove and find a subject they enjoy, so many possibilities seem to open up. Richard Prince talks about the days when he worked at the clip desk for a big photo magazine, and every time a new cowboy ad from Marlboro would turn up, he’d think, “Oh look, there’s another one.” And it’s like you're finding money on the street, or seashells on the beach. I can feel that with this catalog work.