The undisputed doyenne of performance art, Marina Abramovićpioneered the use of her own body as both the subject of and medium for her work. Since her early, radical performances in her hometown of Belgrade, she’s gone one to become one of the few—very few—performance artists to achieve a level of recognition beyond art-world inner circles, mostly through her blockbuster 2010 MoMA piece The Artist Is Present and her subsequent appearance in Jay Z’s video for his song “Picasso Baby” (though the two performers have reportedly since had a falling out).

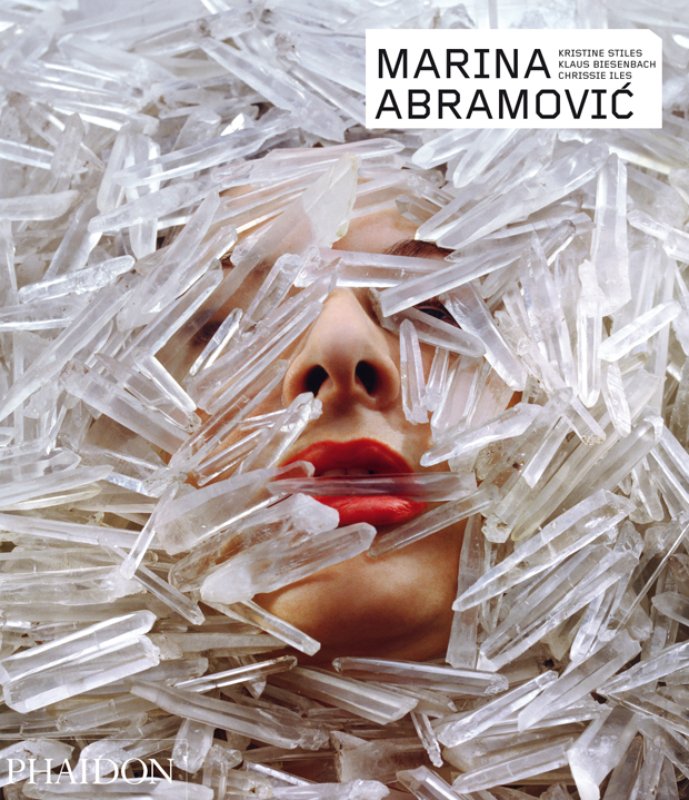

In this intimate interview with her lifelong friend and champtionKlaus Biesenbach, the famously forward-thinking director of MoMA PS1, the artist looks back on her trailblazing and continuing career as part of herPhaidon’s monograph Marina Abramović

Klaus Biesenbach: Your early sound pieces seem to be very much about control. When you think about The Bridge (1969, Belgrade) or the announcement (Airport, 1971, Student Cultural Centre, Belgrade), were these pieces meant to be disruptive and commanding?

Marina Abramović: This is a really good question. I think I was dealing with destruction even earlier than that. I think it comes from my childhood. My mother always used to give me sets of instructions for what I should achieve every day—to learn a certain number of French words, for example, or what I should eat, what kind of books I should read, what time I was supposed to be home. That time of my life was based in a frame of discipline. So my earliest work, I remember, was my dreams. I had a kind of destruction in my head that I dreamt about, and then I would paint the dreams.

Later on, when I went into painting clouds, I had this idea that the clouds had a complete system—the clouds are in the sky, they are projections, there are the clouds that are coming in, clouds that are already there, black holes, ones that are disappearing. So there was always some kind of system that I followed.

When did you paint the car accidents?

I painted the car accidents after the dreams. I was about nineteen. It was very strange because first of all I wasn’t fascinated with normal cars. I was fascinated with these big green trucks, these kind of Yugoslav trucks. I would hear about the accidents, and then I would go there and try, through some of my father’s connections, to get as close as possible and see the smashed or overturned truck, and I would take photographs and bring them back home and try to paint them.

And when you look at the paintings now do they look like a student’s paintings? Do they look naïve or bad?

No, I don’t think they look naïve or bad or like student paintings. They are more abstract. The problem is that they’ve all been given away to friends. I only have one left. During the second period I would go to the toy shop and buy small little trucks and bring them to highways and see if I could get the real truck to smash the little toy truck. I would then paint these big trucks being smashed by the little trucks, the toy truck being untouched and the big truck being smashed. After that I moved on to the clouds. From working on the clouds I would look into the sky constantly. One day I saw twelve military planes passing by, and they made this incredible drawing in the sky. The lines appeared and disappeared, and then there was blue sky again. So I went to the military base and I asked if they would give me twelve military planes to make a drawing. They called my father to say, "Are you crazy? What does your daughter think it would cost to give her twelve military planes to play with?"

But what was your father’s position that you could even ask that?

He was a general in Tito’s army during the Second World War, and then later on he was a civil judge. We constantly had his friends at our home, including the chief of police. So I knew these people, and it was easy for me to get to these places. But it was very interesting for me because when I saw the planes and the drawing in the sky, it was like a revelation. That was the moment I stopped painting. Why did I have to use something two-dimensional when I had freedom to use anything I wanted? I could use fire and water and the body and sound. And that thought became sets of instructions and drawings, like conceptual works, which I could not realize. It was always about instruction, from beginning to end.

One of the first instructions came about when I proposed putting on an exhibition in a gallery in Belgrade while I was still in the academy. It was about fitting washing boards around the gallery. The public would come in, take off their clothes and give them to a group of women or men or whatever, who would wash their clothes, dry them, iron them, and give them back. And then they could go out clean. The proposal was absolutely refused.

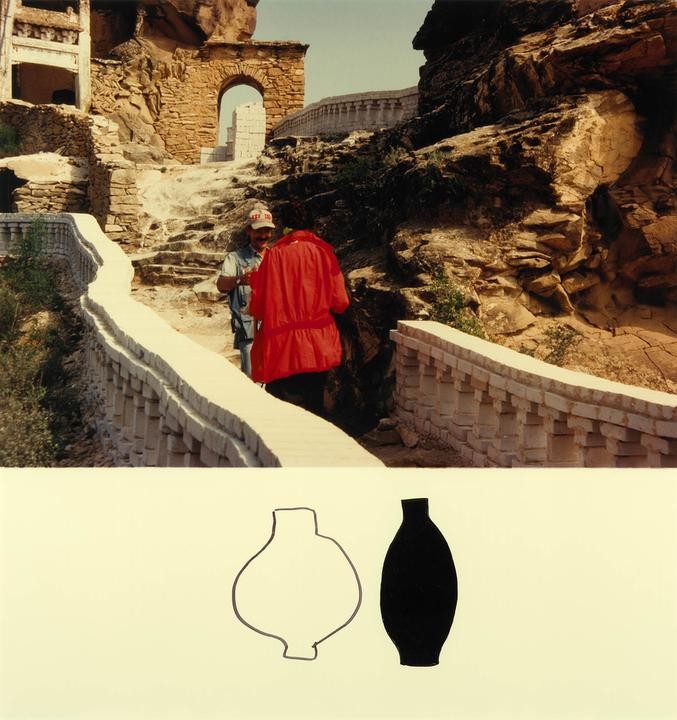

100 Pisama/100 Letters, 2008—available on Artspace

100 Pisama/100 Letters, 2008—available on Artspace

So what was your first serious exhibition?

That would be the exhibition of paintings I had instead of the refused concept. The gallery was called The House of Youth.

When was this?

This was all happening before 1968. In 1968 there were big demonstrations in Belgrade, and at the time I was the student secretary in the Communist Party at the academy. Student secretary was an important position. I was very proud to be communist. This was a time when there were demonstrations everywhere, in France and Germany, and we wanted a change. We were asking Tito for thirteen points, like more freedom, a multi-party system, freedom of expression so that people could write what they wanted and criticize the system. We also wanted better food and a cultural centre, a place where we could make art.

My father gave a talk on the square, and he was completely on the side of the students. My mother was against it. She had never really been a true communist like my father, so it was like I was on his side. One afternoon Tito had to give a speech, and if he didn’t accept the conditions we were supposed to stay in the barricades and go to war. I was ready to die for these ideas. I had that kind of strong passion.

In the morning I went to the committee centre to find out what was going to happen, and when I arrived people were preparing for a big party. I said, "What are you doing? How do you know what Tito is going to say?!" And then one guy looked at me like I was so naïve. "Whatever he says, it’s over." I didn’t understand until that moment that Tito had given a talk, and out of the thirteen points he had accepted only four totally uninteresting things, like better food, but not the major things.

One of the things given to us was the Student Cultural Centre. The building was previously where the secret police had played chess and their wives played knitting. So we got this centre. That evening there really was a party, like everything was fine. I was so disgusted by the whole thing that I burned my communist membership and never became a communist again. At the same time, in the square, my father threw away his communist membership. That same evening the soldiers brought it back to him.

But that Student Cultural Centre became the main focus, a place where I really knew art was happening. The first director of the Student Culture Centre was Dunja Blazević. She was the daughter of the minister of the state of Croatia, so she had this kind of coverage and protection from her father’s position, and we could do things that couldn’t be done anywhere else. The first thing she proposed was to create an exhibition in which everybody brought something that wasn’t art, something—an object or thing—that actually provided inspiration for the work, but not the work itself. And it was called “Drangularijum.”

One person brought the door of the studio, because for him the door was the most important part of his process—when you open the door you open a space that you have to enter to create. Another guy brought an old blanket, because when he went into the studio he always went to sleep and covered himself with this old blanket with holes, and then he woke up and he felt fresh and could work. A third guy brought his girlfriend, saying, "I always need my girlfriend," and she was sitting there. Another one brought an old radio. He said, "I always listen to the radio in the studio." So he went to the radio station, and in the space we transmitted the show of him talking through his old radio.

I brought three objects, two little peanuts and a black sheepskin, which I nailed to the wall. I called it Cloud With Its Shadow (1970), because at that time I was painting clouds. This was the first time that we had the structure and infrastructure to put on an exhibition. After that exhibition I was the only woman, and there were another five guys [Raša Teodosijević, Zoran Popović, Ukrom Gergelj, Era Miliovejić, and Neša Paripović]. We all started working with things that weren’t traditional art. I was the only one who did performances and sound installations.

When you started with sound pieces how important was theelement of time?

I think that the concept of time, for me, always meant "forever." I never thought that I had to make a work two hours or three hours long. I wasn’t aware of performance art at that time. I was aware of the participation of the people, and I was very interested in how I could change the environment with a sound. Like in The Bridge—visually you can see that the bridge is there, but with sound, the bridge disappears.

But when the sound is so strong it affects your situation. It becomes like an imposition.

That’s true, but then the sound becomes more and more important. In my big exhibition in Zagreb [Gallery of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, 1974] I had the whole museum for myself, about six or seven rooms. I did a performance on the first evening, Rhythm 2. Afterwards it was all empty, and in each room there was just a metronome on different speeds—adagio, allegro, andante—and in the last room the metronome was still. I think this was a really important piece from that time—the idea of the empty space and being aware of the time passing at different speeds.

The pieces entitled Rhythms are also connected to the vocabulary and grammar of music. What was your relationship to music?

It was zero. My mother sent me to piano lessons, and after a year the teacher said to my mother, "You know, I’m just taking your money for nothing. She absolutely doesn’t have any talent for music." No, these works were related not to music but to sound. But in my mind they were really about time.

Can you remember when you started visualizing or expressing time as sound? I think this is quite an important characteristic of your work.

I think I did this most consciously in Rhythm 10 (1973). Rhythm 10 wasn’t just about playing with knives in between my fingers. There were two tape recorders. One recorded the sound of the first performance, and every time I cut myself, I changed the knife and rewound the entire tape. Then I would play it, and while listening to the first sound I would concentrate and repeat the action by cutting myself exactly at the same time. I only missed it twice. And then I had a second tape recorder with the doubled sound. So the idea was to find out if I could put together past and present, including the mistakes. The mistake synched together, which was such a crazy concept, if you think about how impossible it is. But I was always thinking about the past and the future, and then about the present.

All my new work now is about time. And it’s about the fact that actually by being in the present you stop time—you don’t think about the past or future, you’re just there, with everything turned into that idea of here and now. I really can’t recall the first time I thought about this. I only know that it was definitely the most clear for me in Rhythm 10. But there were two parallel ideas at that point. One was about time, but the other was really about consciousness and unconsciousness. I could not accept that a performance would have to stop because you lost consciousness. I wanted to extend the possibility, and that’s why I made these two pieces, Rhythm 2 and Rhythm 4 (1974), in which the performance continues even if the performer is unconscious. I didn’t accept the body’s limits.

Rest Energy, 1980, by the artist and Ulay

Rest Energy, 1980, by the artist and Ulay

Your early performances are about duration and a linear concept of time, but when you look at your pieces now, and how they are presented, they’re loops. Rest Energy (1980) lasts only a few minutes, but now you present it as a never-ending, timeless picture.

The idea of the performance having a beginning and end was very difficult for me. In Rest Energy there is a beginning and end, because even if it’s looped you still see us release the bow and then start again, but in many other performances you don’t see that. For me it was and is very important that the public never sees the beginning and the end. It’s very important that this image continues. It’s almost like our planet endlessly moving around the sun. And we’re endlessly moving around the galaxy. The entire universe is looping, and I like to simulate this looping in performance.

But when you think about presenting or re-presenting performances, going back to the very beginning, when you started, what kind of images did you want to create? What was your intention?

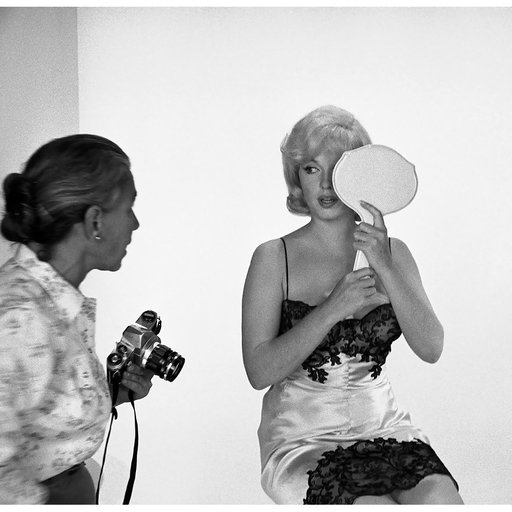

I had a very strong sense of historical responsibility. From an early age I always thought about documenting. I think that’s why I have better documentation than so many artists from that time. Even if people questioned whether we should document performance or whether it was something that should just stay in memory, I always documented, even from the early days, with the Rhythms series.

Did you photograph them or did you hire an assistant?

There were different cases. For Rhythm 2 a person was there who I instructed how to photograph—frontal and then close-up images of the hands. The photographs are always frontal, always very static. I immediately got all the negatives. I didn’t know whether I was going to make big photographs or small photographs, but I knew that I wanted to have documentation. I was in control of it, and this is how I wanted it to be.

When I performed Art Must Be Beautiful, Artist Must Be Beautiful (1975) I didn’t have any experience with the video camera, so I didn’t give any instruction to the guy who was filming. Immediately after my performance I saw the material, and I was so disgusted, so unbelievably appalled, that I literally asked him to erase the recording right there on the spot. He was moving the camera, panning, zooming, doing solarization. It was such unacceptable material, I mean it was like he was making his own work. It wasn’t my work. And I redid the performance in the back room just for the video camera and instructed him the same way that I had instructed the photographer. It was good that it happened at this early stage, because from that moment I had a very clear idea of how someone should be instructed to make the documentation.

The Energy Blanket, 2010, available on Artspace.

The Energy Blanket, 2010, available on Artspace.

But this sounds as if you were not documenting. It sounds as if you were editing and producing. I think there is a difference between the word ‘documentation’ and creating an image.

Yes, but again it’s very mixed. For Art Must Be Beautiful it was like that. When we made Relation in Time (1977) we had sixteen hours in the gallery without the public. Only the last hour was with the public. We didn’t have enough money at that time to film all sixteen hours. We placed the camera, and the people who worked in the gallery would come and shoot three minutes every hour. So for every hour we have three minutes of video. Then in front of the public we shot the entire hour. Everything was done on video, but later on we redid some of the performances for film. We never shot straight to film because it was impossible to shoot continuously.

How about the objects from your performances?

My attitude about objects from the beginning was that I didn’t care. I didn’t want to create any kind of fetish situation. I was very against this idea of saving objects from the performance, like Gina Pane, or Chris Burden, who saved the nails. I didn’t want them and I didn’t have much, like Art Must Be Beautiful—

You didn’t keep the brush?

No. Every time I did this performance I would just go and buy a brush, and that was it. What really made me angry was Rhythm 0 (1974). Rhythm 0 involves seventy-two objects, including knives and a pistol with a bullet. When the performance was finished the gallerist asked me what to do with them, and I said, "Just throw them away." But when the curators of “Out of Actions” (Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 1998) asked me if I would present Rhythm 0, I thought it would be ridiculous to represent it with small images of the performance and that it would be much more interesting if people could see the objects. So I sent the curators a drawing of the table as it should be built and covered with a white cloth, and I gave them a list of seventy-two objects to buy, including the pistol (which, because of American law, had to be locked so that it couldn’t be used), and behind that there was to be a slide projection of the work.

Then I heard that the gallerist had written a very angry letter saying that he had the original objects and that I was not allowed to display these objects. Original objects? There are no original objects. Every time I do a performance I will always buy new ones. But things change. In the 1970s I said that I would never re-perform performance. I think differently now. I said I would never have these relics, but at the same time I kept the Chinese shoes and the Chinese stick [from The Lovers (1988)] and white coat [from Balkan Baroque (1997)].

Rhythm 0, 1974

Rhythm 0, 1974

That’s my next question. Do you perform—and did you perform—to create images, memories or oral history? You make a performance, and from it there is an image that people carry in their minds. It becomes a memory. And if people talk about it, it becomes oral history.

Again, this changes from period to period. In the 1970s for me what was important was to make something really disturbing and dangerous, some kind of image that would shock the public and create a space in them so that they could receive something new, giving them a different awareness. This was especially clear in the piece called Sound Corridor (1972), which is actually quite an important piece. It was done in the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade. The entrance was a glass corridor, and in this glass corridor I put very large speakers on each side with sensors so that when then public came in they activated the speakers, which created the sound of gunfire. By crossing that corridor to enter the museum, they were killed with a sound. And when they entered the museum there was total silence. But it was not any kind of political statement. What was important for me was that by entering that space you left everything behind you, because the shock of that sound completely filled the body, and when the sound stopped, you went into the silence and were empty to receive art.

For me performance was creating that kind of empty space by doing something so unexpected, strange, and weird. Much later I read about this Tibetan tradition where they built a bridge under a waterfall and made a little hut and stayed there for three or four years. The sound of the water was so strong that it completely stopped the thinking process. The sound would constantly be in their bodies. Then after four years they would leave, and there would be such a silence, a completely new space of total silence that allowed them to receive things. It’s like a cleansing.

[related-works-module]

Three very short questions, you can say yes or no. Are you a conceptual artist, or at that time did you consider yourself a conceptual artist?

No, I was immediately thinking of the body art.

Second question—did you or do you consider yourself a political artist?

No.

Third question—did you or do you consider yourself a feminist artist?

Absolutely not, never.

If someone had asked you in an interview in 1971, "Marina Abramović, describe yourself as an artist. What are you actually doing?",what would you have said?

I would have said, "I am doing sound installations, and I’m doing body art." Sound installations were not connected to body art in my mind.

And if you had to do that now, what would you say?

I would say that I’m a functioning artist. That’s it. Just an artist.

This brings me to another point. I wrote down a couple of words, and I’ll just give you the word and you can comment. How important to you is the concept of boredom?

It’s very important. There is something that John Cage always told me, that you have to go beyond boredom or behind boredom. In some of my new pieces when there is nothing happening I try to take every possible kind of expectation out of the piece. There is no beginning, development, and end. It’s just nothing. It’s just presence, pure presence. And the first reaction of the public can be boredom, but if you go beyond that boredom, something has happened. So boredom is very important. It’s almost crucial.

Are you ever bored, Marina?

No, I am really not. I want to recall a wonderful Nam June Paik piece in Kassel a long time ago [Documenta VII, Kassel, 1982]. People were invited to his performance, and he took the microphone and repeated for about an hour, "This is going to be a very boring piece. Please leave the room. This is going to be a very boring piece. Please leave the room." And after ten, fifteen minutes, the people really just started leaving. I stayed there. I was so interested to see what was going to happen. Maybe about twelve people remained. And then he made a wonderful concert. It was like a kind of threshold that you had to pass in order to get something special.

The idea of doing nothing is so foreign to our culture because we constantly have to do something or achieve something, even in our free time. Again, coming back to the Tibetans, they told me, "When you wake up in the morning and you have enormous amounts of energy what do you do? You go shopping or call friends or do whatever and spend energy, and then you go home, have a drink, get very tired, and sleep. But if you have all this energy, just sit in the chair and do nothing and see what happens. All this energy that would go outwards turns inwards, and something else happens."

You asked about my work in the beginning and whether I sought to create space and to shock. Now more in my work is how I can find a kind of formal structure so that I can actually elevate the spirit of the audience. That’s actually my main objective, not to put spirit down—there are so many works that do that, it’s too easy to put down the spirit of human beings—but to create some kind of work that is almost empty of content but which still has a kind of pure energy that elevates the spirit of the spectator.

Marina Abramovic, the definitive monograph from Phaidon, available on Artspace.

Marina Abramovic, the definitive monograph from Phaidon, available on Artspace.

We talked about boredom. Next question—how important is danger?

Ah, it’s very important to me. Danger is important because it brings time to the point of the here and now, to the present. Your mind escapes every single second. Every time we blink there is another thought. So to stop time, to just be in the present, you have to be in an extreme, dangerous situation. That’s why I stage situations where I have to do some dangerous things—so that the public and I are in the space at the same time. For The House with The Ocean View (2002) it was very difficult to be in the present constantly for twelve days, so I always tried to stand on the edge, over the ladder with knives, where I might fall on the knives. That was the point. Even if I lost consciousness or was too dizzy because I didn’t eat, or just physically weak, for me that moment was the right point to stand there, because that was the point at which I could be in the here and now, in the present.

To keep going through words, like a vocabulary, how important is pain?

Pain is the same thing. You see, there is so much secret knowledge being preserved, because pain is like a door. You have to enter through the pain into that other space. That is what all superstition is. That’s why Aborigines at ceremonies will literally become clinically dead in order to understand what is behind all these things. Our minds will try everything to mislead us and say, "No no, this is painful. I can’t do it." And actually when you understand the pain it doesn’t matter anymore. You can do anything. You can stop the pain, you can remove it from your consciousness.

That is very difficult to believe, because some people, like those battling a disease, have unimaginable pain.

Yes, but this is again a different story. We are talking about consciously going through the pain, staging the pain and going through it. Every ceremony, every ritual from ancient times until now, including the Catholic Church or the Orthodox Church, stage rituals that include pain. When you are sick, when it’s something inflicted without your will, it’s a different story. Torture is not something you want to go through. Neither is the pain of being sick. This kind of pain is another thing. When you stage the pain we are talking about how to actually understand how the mind and body work and what pain exactly is.

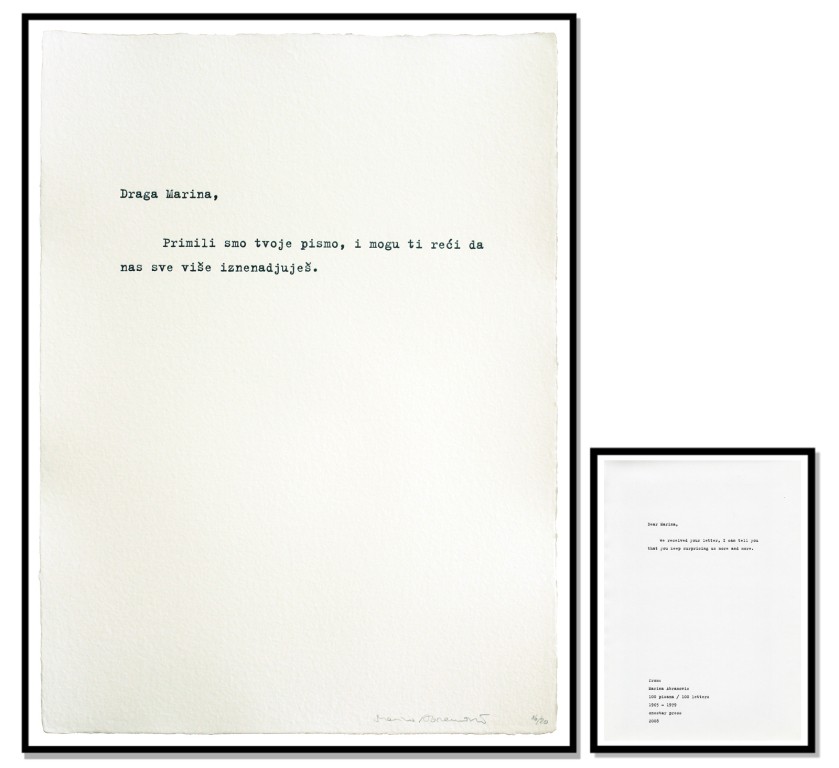

Spirit House—Dissolution, 1997

When you say this, one could say that your work is very rooted in mythology and even in religion, not only because you are talking about the Dalai Lama, and about monks and Aborigines, but because some of your works nearly look like Christian martyrdom and self-flagellation. So I think the ritualistic quality of self-inflicted pain has a very mythological or even religious quality to it. Do you need to feel the pain?

Valie Export said a very interesting thing. She said that if I inflict pain on myself in order to liberate myself from the fear of pain, then pain is okay. That’s a really good statement. So I somehow become friends with pain. I don’t need to inflict it anymore. That’s why I did The House with The Ocean View. But there is another type of pain that has something to do with mental limits, about which there is so much more to learn.

But the reason for me that other religions and rituals and ancient civilizations are so interesting is that they master the body in so many ways. I mean, if you go to the East, there is total control. They can stop blood circulation. They can create such a heat in an extremely cold environment—minus twenty degrees—that they can sit naked on the snow and melt it or dry wet towels on their shoulders. I see myself as a bridge going to the East to get the knowledge and going to the West to transmit it in the form of performance. People don’t go to the temples anymore. They go to the museums. And to me performance can be a great tool to create some kind of platform for that kind of experience.

How important is the concept of shame for you?

Unbelievably important. It’s very interesting because shame is something people don’t deal with as much. To do things with your shame or say things that you’re ashamed of or to expose yourself in a shameless way, it’s like opening yourself to the audience. Being so vulnerable, this is something that really breaks down the walls between you and the audience. And I think it’s really important. For me one of the people who I very was impressed with for doing something with shame was Leigh Bowery. He would go to clubs and dance, and in the middle of this came the performance. People there were ashamed of looking, and you were ashamed for him, and it was an amazing experience. We don’t deal with shame. We are even ashamed to admit certain things to ourselves, never mind to friends or large audiences. So that one is even more interesting for me right now than pain.

Is there, for you, a difference between performing and acting?

Yes. For me acting is taking on the role of somebody else, and you’re pretending to have the feelings that you are showing in front of an audience. Whereas performing is real. When performing you just have an outline of the concept, and then you go inside it. For me, there is the danger that if the performance is short, you act. If you repeat the piece too many times, there is a danger that you start acting, because you already know everything, all the elements. But if you put on something that lasts four, five, six, seven hours, it’s impossible to act.

In your theatre piece The Biography (1992) are you acting or performing?

It’s absolutely a mix, because the performance element in it is real every time. It’s a question of concentration, how to concentrate in order to create three hours in two minutes. It’s very very fast. Originally I would start the performance slowly and then build up the intensity. If I did something like Rhythm 10, here you start with intensity and then you can’t act because you play with the knifes so fast, and there’s a real possibility of injuring your hand.

Who is the author of The Biography?

The idea of The Biography started as a collaboration work with Charles Atlas in 1989. Since then I went and just invited different art directors to direct my life as a theatre piece. By rearranging my material they always make a new way of seeing my own life. For The Biography Remix (2004) with Michael Laub, he didn’t do anything chronological. He took the Yugoslav part out of it completely, which I think is important, but he didn’t think so. He added elements that I wouldn’t have, so everything looks new to me. And now it’s Robert Wilson, so we will see what he is going to do. But all the text is mine. All the materials that I give to every director are mine. I just give them all the material, and they just re-edit it. With Michael Laub I suggested that I wanted to have my students play me so that they, by actually being on the stage, were the literal demonstration of this transmitting of knowledge. With Rest Energy I do it with Ulay’s son, who plays his father in The Biography Remix, and then give it to my student to do it right after me. So that’s exactly what it is—a demonstration of the possibilities of re-performance.

In Seven Easy Pieces (2005) you performed seminal performances of other artists. Do you see your own pieces performed by others now?

Yes, absolutely. And you know, not every piece can be reperformed by anyone, because some pieces put whoever is doing them in potential danger. I could not accept it if I didn’t have some kind of assurance that the person would be capable of doing it. But I now have these two people, Eva and Franco Mattes [0100101110101101.org], who came to me with this idea of having three or four of my performances made for Second Life. They have done Chris Burden’s Shoot (1971) but they didn’t ask him for permission because they thought nobody needed permission. But after they saw mine they decided to ask me for permission, and I was extremely enthusiastic about this. I think the possibility of Second Life is that the performance takes another form, that of a cartoon, and becomes an Internet thing.

Will you basically create a storyboard, libretto, or instructions for how your pieces should be re-performed, or do you want people to see an image and then do it?

No, I think that it’s really important to have complete instructions and also certain foundations in order to decide, if I’m not alive, whether a person is able to perform the piece or not before he is given permission. It’s like, if you know how to play the violin, you can play Bach. If you don’t, you can’t. You can’t just let anybody perform these things, because you need a certain … not just knowledge of performance, but stamina and concentration and willpower. So these pieces are not all easy to perform. Some are, others not. But I see that a performance can take so many different forms. With Second Life it is not human anymore—it’s a cartoon—but the idea continues, which, for me, is interesting, using new technology and thinking about how it can develop in the future.

In an interesting way performance has no copyright.

Yes, that’s what I argued about because it’s so unfair. If you make the piece, you’re the original owner of that piece, so you should be asked. But there is no law that states this, so I think it’s totally unfair that there is no law that states the property of a performance. If somebody takes it into fashion, MTV, theatre, whatever, they should actually pay the rights for that thing. But performance art is nobody’s territory. Before, video and photography were like this, but not anymore.

Performance has always been some kind of in-between medium. I always want to compare performance to the phoenix. In the 1970s there was body art. In the 1980s there was no performance. At the end of the 1980s club culture arises, and young artists start doing video in the studio, and the video was performative—it was performance that was actually exposed as a video. They were mostly three, four second loops, which I argue against again because they were endless loops of something that was very short but suggested enormously long periods of time. In real performances in the 1970s it was very long periods, but the artist went through an experience of three of four or five or ten hours. In the work of young kids who made an endless loop of, I don’t know, one and a half minutes in the studio, the experience was not there, the experience of them doing it. So it’s another story. And then performance moved into the theatre, dance. Dance has so many elements of performance art. Then therewas Jan Fabre, then MTV. Then it went back to the theatre. Then it came back again into interactive installation. And now it goes onto Second Life. It’s always changing.

Do you see a revival in performance in the last seven years? Are performances much more present now than they were ten years ago?

Yes, but not in a pure form, I would say. It’s more with sound and music. I think the future of performance will definitely go back to sound. And I think that something like noise music is extremely interesting. It’s like a new territory. Now there are some things coming up in performance that we don’t have words for. They are in between everything. But it’s based on sound. It’s based on overtones, low vibrations, high vibrations, where they take up the entire space. I think there is something very new coming in the next few years in performance,but it’s not as traditional as we think it must be.

Now each big exhibition has a performance program, and New York has this huge performance biennial [Performa], and there are lots of younger artists like Jamie Eisenstein or Terrence Koh who do performances. I think that performance is actually one of the leading practices right now.

But it’s very interesting how different things are. I went to see Jonathan Meese performing, and the first ten minutes went very well—he has this energy and there’s something there—and then the moment the beer came out and he started drinking it became something like Fluxus or a happening. It was like, ‘Oh god are we going through this again? That you have to be drunk to be loose, and you completely disintegrate in front of the public?’ Everybody was enjoying it, but I really had a problem with losing control in that way. It’s very old-fashioned. Maybe the new generation has forgotten, but that’s exactly how it was in the 1960s.

I was thinking about coming to your more recent biographic situations. You did Balkan Baroque in 1997, which I think is very autobiographical. And more recently you did Balkan Erotic Epic (2005), in which you feature the spiritual or mythological backgrounds of the peasants of the country you’re from. Having spent so much time elsewhere, do you feel like a nomad? Do you actually have a culture where you feel at home right now?

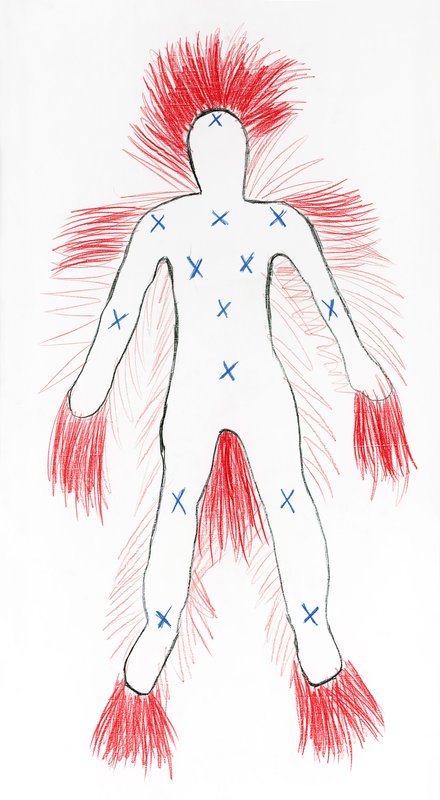

No. When I left Yugoslavia I absolutely didn’t have any interest in the Yugoslav traditions or culture. I wanted to go as far away as I could, to be interested in anything else. For me these multi-cultural elements were a very important part of my work from very early on. Nightsea Crossing/Conjunction (1983) was one of the inspirations, because never in the history of these two cultures had Aborigines and Tibetans ever met in a normal life, and we put them together inside a performance. And only after that could I go back to Balkan culture, after forty years of being away from my own culture. Because then I could see the big picture. I could not have seen it from within that culture. I can only see it from outside. But I don’t see it as a culture that I am part of. It just interests me. There is a piece called Expiring Body (1998) that is quite interesting to think about now. I created this kind of video body starting with the head of my brother, representing the brain, and the torso was an African man dancing like a rattlesnake. Then there was an Indonesian man walking on the fire, just his feet. So this "expiring body" is almost a totemic body which represents this nomadism and my interest in many different cultures.

Do you think you are ever at home, culturally? Do you ever say to yourself, "This is where I belong?"

No, I don’t. I have asked myself this question so many times. I think that home is me. Any hotel room is home. Any place can be home, but actually home is inside me. I don’t really have any space where I would call home. And it’s happening even with languages now. I don’t have dreams in Serbo-Croatian anymore. I mix English, Italian, French. It’s a mess. I think it comes from this extensive traveling. There were times when literally every four or five days I would take a plane somewhere else. So everything became relative, in a way. I always have this idea that I see everything from an aeroplane. I see the totality and not the particular parts of the planet.

At age twelve you had a painting show, then when you were eighteen you had a show at the cultural centre, and then you had your first museum show a couple of years later. When you think of Marina Abramović back then and Marina Abramović now, are you the same artist?

You know, I can answer this in very funny way. A few years ago when my grandmother was still alive I went back. All my old stuff was still in her place. I was looking through the cupboard and found this little diary that I used to have when I was like twelve or fourteen. I had written down what happened every single day. And it’s just incredible. I thought that I had gone through so much transformation, that I had made so many things, that I had become so wise, so knowledgeable. And as I was reading this diary what struck me was the realization that nothing had changed. All this shit is there. It’s only different names. But all these little things—suffering, crying like a little baby for the stupid things, being hurt—nothing has changed. I really think that change has to appear in an incredibly dramatic way. It’s only if you have a life-threatening sickness or suffer some great loss or great accident that something really changes. But normally, even if you do so much, things don’t change as you want them to.

It’s so interesting that over forty-five years you never stopped dealing with certain ideas, like the representation of time, your body in time, making people aware. Perhaps when you wrote when you were fourteen you were already the Marina you are now.

But you know what is amazing is that I never doubted, never thought of being somebody else. I never thought, "Maybe I should do something else. Maybe I’m not an artist." There has been a complete line, like one of these highways. One more thing that I didn’t mention to you—when I lived in Yugoslavia I was already thinking about a retrospective, and I had just one idea. For my retrospective I was going to take a magician and invite him along with an audience. I was going to be in the audience, and he was going to be on stage with instructions in his hands. He was going to read the instructions and ask anybody from the audience to come onto the stage and be hypnotized and under hypnosis do any of the performances of their choice, with me as a viewer. I could watch all my performances being done through the hypnosis of somebody else. And I had this idea so early on.

When was that?

That was in 1975. But you know, it was funny because I didn’t know how else to get anybody in a healthy state of mind to do any of this stuff. So the only thing I could imagine at that time was to hypnotize them! But I never did it.

[related-works-module]