So, you’ve invested in a Frank Stella print. Excellent choice! It’s framed, up on the wall, and your friends are coming over to admire the new work. Do you know what you’re going to say? Do you know which major 20th century art movement he is most closely associated with? Do you know whom he was influenced by, and who he has influenced? And how does his work do at auction? Who are his friends? Who was his famous babysitter? Why was he arrested in 1982? And what has Moby Dick got to with all this? What do you mean you have no idea? Quick! Read this piece, and you won’t be stuck for conversation around this important, contemporary artist when friends want straight answers.

Frank Stella ? I know this. He's the original minimalist painter, right? Well, that’s certainly what he’s known for. Stella, who was born on May 12, 1936 in Massachusetts, is best known for his Black Paintings, a series of 24 canvases, each consisting of bands or stripes of black enamel house paint on raw canvas. Displayed most famously as part of the Sixteen Americans show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1959, back when Stella was still in his early twenties, the series is commonly referenced as an important starting point within the minimalist movement which developed in the following decade.

Is that the right way of looking at those early paintings? Maybe, maybe not. While these paintings are seen as revelatory, Stella actually credits a Jasper Johns exhibition from 1958 as his own source of inspiration. He was particularly impressed by the bands of color in Johns’ Flag painting. “'It was hard not to be impressed,” he told the Daily Telegraph’s Alastair Sooke back in 2011. “'I was working on a particular painting,” he goes on. “And I remember I got mad at it. So, I painted over it, and went to bed. When I looked at it the next day, it didn't look that bad. All I'd done was simplify it by painting out the bands all black. But something was happening. It had a kind of presence. That was the beginning.”

Today, Stella acknowledges the Black Paintings’ importance, but he doesn’t like to dwell on it too much. “When you see them, you can say, ‘Oh, that’s from the 1960s.’ But the 1960s didn’t live on, and so I think it doesn’t have any real resonance anymore,” Stella said in his 2018 Phaidon monograph , “except in the work that’s made to look like art, but isn’t art. I didn’t want my work to live on continuously as a conversation or product of the 1960s, the product of who I was as a very young artist.”

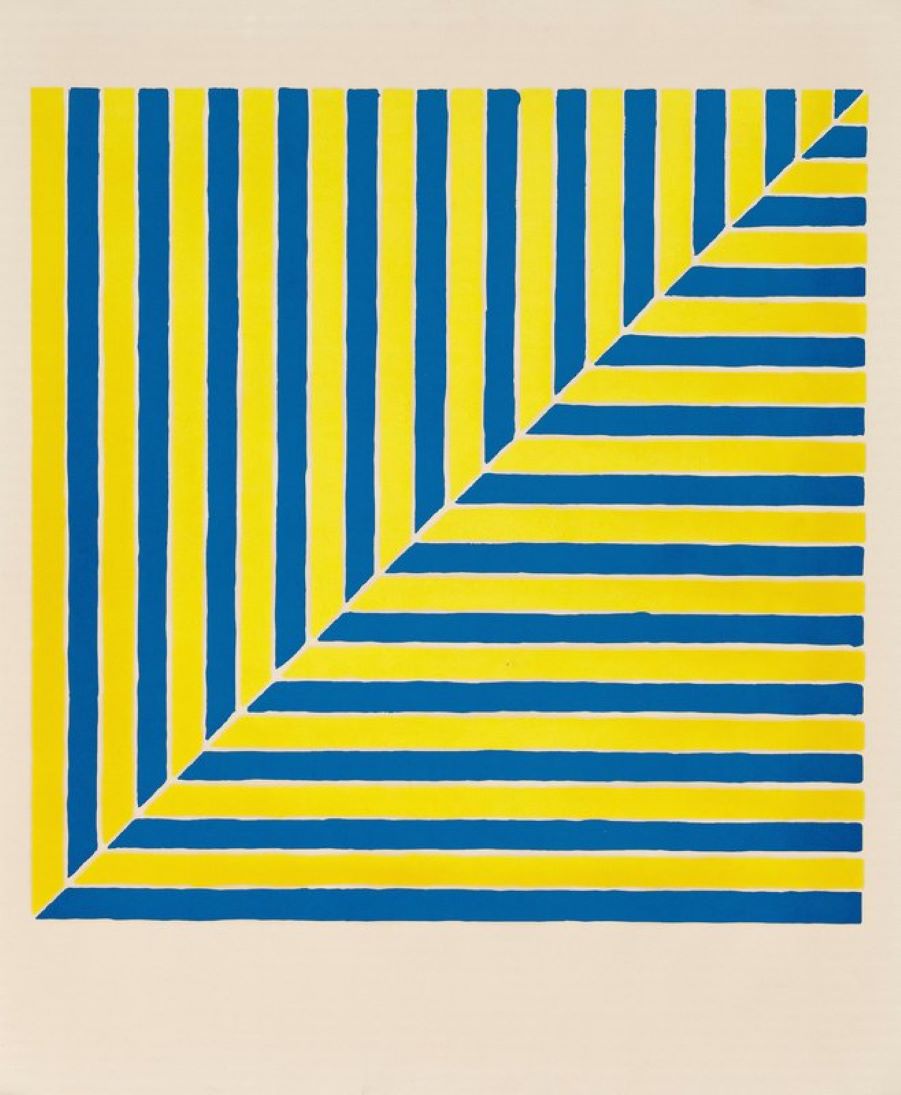

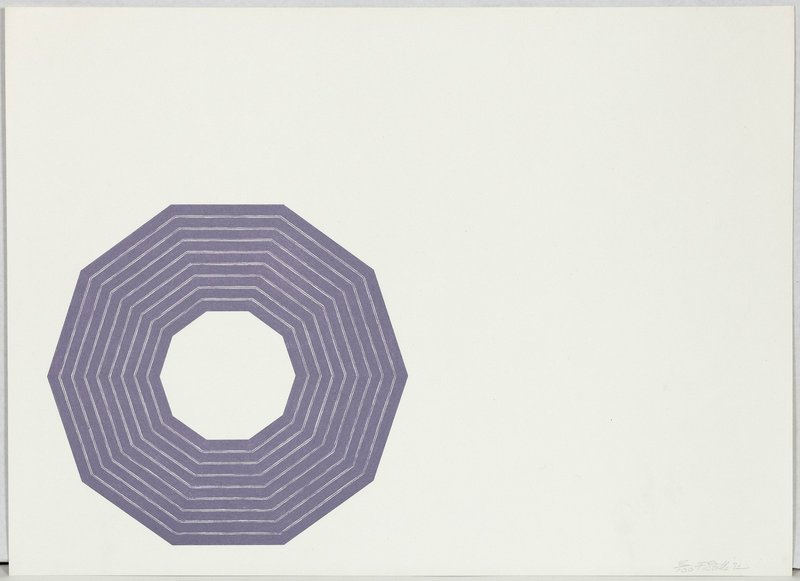

Frank Stella -

Kay Bearman

(1972)

Frank Stella -

Kay Bearman

(1972)

So, what else has he done? So much. He’s developed shaped canvases and worked with geometric abstraction; he’s created simple, abstract colorful works named after the American paint firm, Benjamin Moore; he painted a series inspired by the pre-war wooden synagogues of rural Poland; there is also a great set of paintings inspired by and named after Moby Dick; there’s a series drawing on the plumage of exotic birds; there’s a number of Cone and Pillar paintings, each toying with the experience and notion of space, and each named after an Italo Calvino story (the painter met the author while teaching at Harvard); and Stella has also created a series of 3D printed works named after the eighteenth-century baroque composer Giuseppe Domenico Scarlatti.

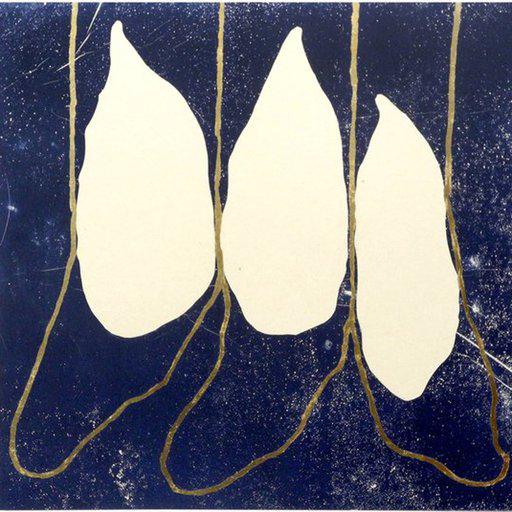

Frank Stella-

Les Indes V

(1973)

Frank Stella-

Les Indes V

(1973)

Wow. That sounds really varied and innovative. How has the market responded? Collectors currently prize Stella. Having had a rough few decades - “The 70s were a struggle,” the artist has said, “and then in the 80s, the market changed, and I just went up with everybody else” - Stella’s best work has appreciated significantly, and now goes for very high numbers. The artist’s 1959 Black Painting, Point of Pines, sold for $28,082,500 at Christie’s in New York back in May 2019; his Lettre sur les sourds et muets I painting, a concentric squares piece, and part of the artist’s Diderot series from 1974, went for $7,062,500 at Christie’s in New York in May 2018; while his Double Mitered Maze diptych 1967 sold at Sotheby’s, New York in May 2019 for $4,340,000.

He sounds pretty high-brow. Do I need to do a lot of reading in order to appreciate his work? Not necessarily. Sure, Stella writes, has lectured quite a bit, and is both an excellent art-history scholar, and a lively, general reader, drawing on a wide range of influences in his work. Yet, unlike, say, the Abstract Expressionists , he doesn’t suggest there’s anything mysterious or impenetrable going on deep within the canvas. As he told the New York Times back in 1967, “my painting is based on the fact that only what can be seen is there. It really is an object. Any painting is an object, and anyone who gets involved enough has to face up to the objectness of whatever it is that he is doing.” In short, don’t worry too much about anything going on beyond the stretcher’s frame.

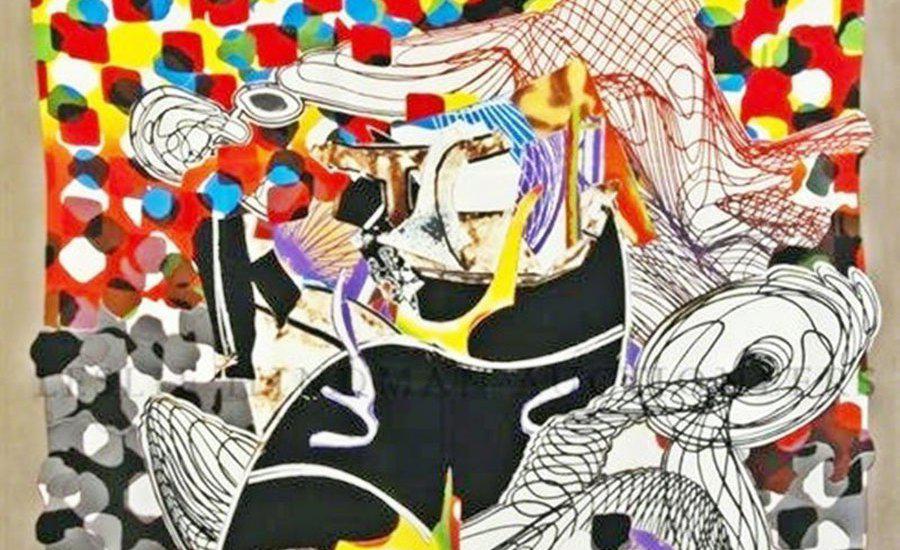

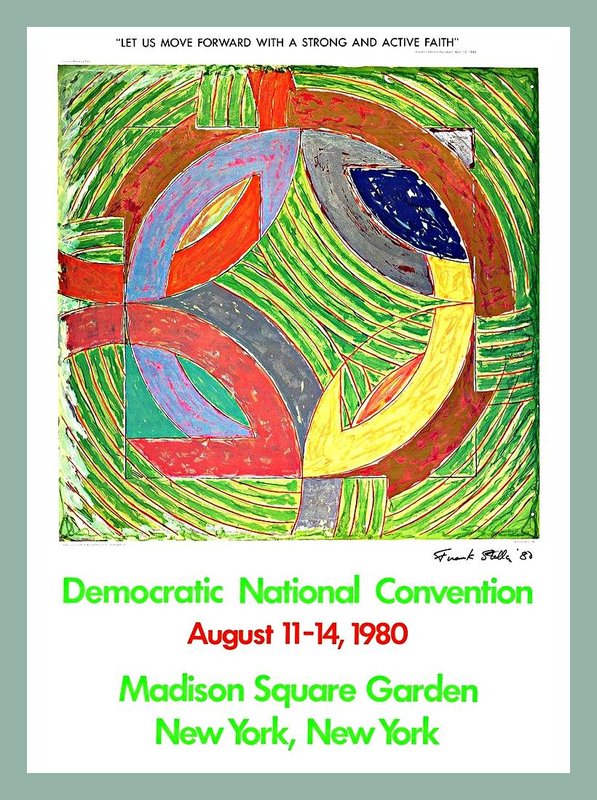

Frank Stella -

Democratic Convention 1980

(1980)

Frank Stella -

Democratic Convention 1980

(1980)

Who are his forebears, who are his contemporaries, and who has been influenced by him? At school, at the Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, he learned about early, European abstract painters such as Josef Albers and Hans Hofmann . He went on to be influenced by the Abstract Expressionists. He was friends with fellow minimalist pioneers, Carl Andre and Donald Judd . And you can see his influence in younger artists, such as Mark Grotjahn , Tomma Abts and Jacob Kassay .

Influenced by the Ab Exers. So, was he ever a bad-boy painter? Well, he isn’t a big rabble rouser, drinking the Cedar Street Tavern dry every night, but he does like good cigars and fast cars. Back in 1982, a traffic cop arrested him for driving at 105mph on a New York State highway.

Is he a painter, a sculptor or a print maker? He’s pretty much all three. While its easiest to think of him as a painter, he has made sculpture-painting hybrids, reliefs, sculptures and conventional, paint-on-canvas works. However, Stella tends to think, talk and write about his work in a pictorial and painterly sort of a way, so, from a viewer’s point of view, that’s often a good way to approach his works.

Frank Stella - Mesh Canvas, 2015

How does he do it all? By hand? Actually, Stella is very keen on the use of new technologies, and, over the past three or four decades has combined everything from the machine-cut of parts to needlepoint with contemporary printing techniques, as well as 3D printing and digital manipulation.

Can I get one, final anecdote? Oh yes. Here's one courtesy Michele Robecchi , editor of Phaidon’s Contemporary Artist Series book on Stella. Many decades ago, Frank took on a young, nascent artist as a babysitter. The artist, a Japanese lady, gave Stella one of her paintings as a sign of gratitude for giving her the baby sitter gig. Fortuitiously, Stella was able to sell the painting to a museum decades later for a substantial seven digit figure."

The babysitter artist's name? Yayoi Kusama . In fact, Stella alongside his friend and fellow artist, Donald Judd, was an early champion of Kusama's and both acquired paintings from her first solo exhibition at the Brata Gallery in New York back in 1959.

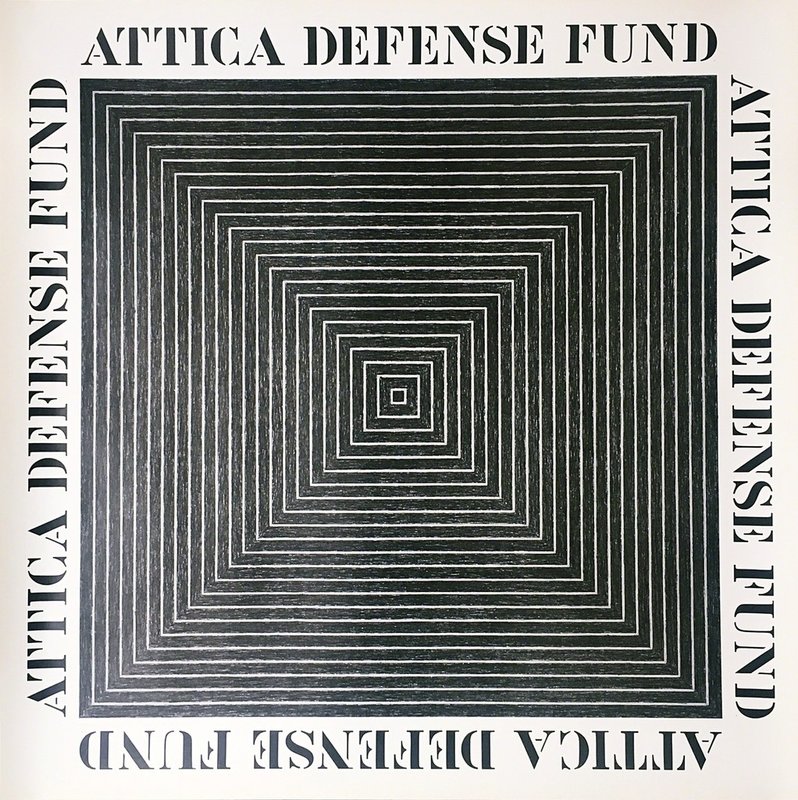

Frank Stella

,

Attica Defense Fund

(1975)

Frank Stella

,

Attica Defense Fund

(1975)

What should I hang Frank’s work next to? For a classic look, try early Kusama , or Ellsworth Kelly , Carl Andre , Donald Judd , Jasper Johns and Josef Albers . For a more up-to-date take, consider putting Frank next to Ulrike Müller , Tauba Auerbach or Marcel Ceuppens . To shake things up a bit, try a little abstract or near-abstract photography, such as works by James Welling , Rafael Assef or Wolfgang Tillmans ; or to really break up the picture plane with sculptural wall pieces: search for Mano Penalva , Rachel Hubbard Kline and C.J. Chueca .

RELATED STORIES

What to Say About Your New Jenny Holzer Print (or Skateboard or LED)

What to Say About Your New JR Print

What to Say About Your New Katherine Bernhardt Print

What to Say About Your New David Salle Print

What to Say About Your New Nan Goldin Print

[FrankStellaPrints-module]